Rebirth of Russian Street art during the protest movement

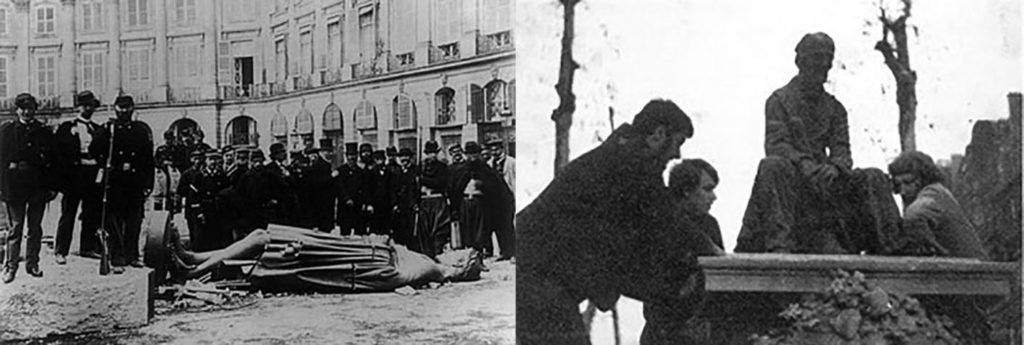

Russian practice of coming-out in public space by avant-gardists1 in the beginning of the 20th century and by actionists of the 1990s2 was political by nature, similarly to contemporary street art though. This is largely due to the fact that Russian public space is always a place of tension and intersection of various interests: business, government, of ordinary citizens. That is why any access to the public space in Russia is a political gesture a priori.

Born in Nizhnevartovsk in Siberian Russia in 1980, Igor Ponosov is an artist, activist and author of several projects and publications relating to urban art. He began his artistic career in 1999 as a graffiti artist in Kiev and between 2005 and 2009 published three books on street art in Russia and the ex-USSR. From 2011 to 2013 he curated the project ‘The Wall’ at the Winzavod Centre for Contemporary Art in Moscow. In 2011 he founded the Partizaning.org website as a platform for exchange among activists, artists and urbanists, and from 2013 to 2016 he curated “Delai Sam” festival, which focused on grassroots indicatives and activism in Russia. He is also the author of the book “Art and the City” (2016).

He has undertaken residencies including the Global Art Lab public art residency in New York as part of the 2014 Arts Leadership Fellows as well as at the National Centre for Contemporary Arts, Moscow, in 2016. Ponosov currently lives in Moscow, where he works as an activist, artist and independent curator of multi-disciplinary projects, focusing on the social environment of the city and its transformation through the arts.

In winter 2011 there were compromised parliamentary elections that provoked numerous protests across the country, at the same time considered as the beginning of formation of more active and socially responsible civil consciousness in Russia. However, the desire for change was already felt in 2009-2010, when rapid development of social networks occurred, becoming a real tool for self-organization of activists and discussion of political issues. Through emergence of independent city media (The Village, Bolshoi gorod and others), Strelka Institute3 and a number of grassroots projects the discussion around a comfortable living in the city with its improvement was initiated. Basically, the question was raised about the “right to the city4“.

In 2012, when the atmosphere of protest movements was fueled with March presidential elections, the displeased mood of protesters reached its peak. In addition to demonstrations, one could see an outburst of self-organization initiatives (assemblies) on the streets, as well as illegal folk art, which was not supported by any artistic practices, but had a huge impact. Such informal folk activity enchanted and encouraged many people, including artists, who later also went to the city to protest.

For instance, at that time the practices of Moscow actionism of the 1990s were actively used by radical artists and art groups of a new wave such as Pussy Riot, Voina, and Piotr Pavlensky (b. 1984). In the same way as the actionists of the 1990s, they declared the issues the most provocative way. Thanks to media coverage, many of these actions became world famous, iconic, and for the West confirming the stereotype of the “wild” rough Russia.

However, these practices could be related to street art only indirectly, because their actions used public space merely as a medium for their statements, and not as full environment for creating their works.

In the street art community, a political agenda was not so explicit though. However, more and more street art artists were switching to political and social themes.

Above all, it can be traced through large-scale and media works by Yekaterinburg artist Tima Radya, who, while not having a graffiti background and not in fact following the way of understanding graffiti as a daily practice5, began to show quite recently, only in 2010. Over the next few years, Tima worked exclusively in street space so zealously that one can only envy the number of his works. Later, the artist became known thanks to political works “Loss of strength” (2011), “You were cheated” (2011) and “Figure # 1: Stability” (2012). Nowadays, working in the style of total street installation, often politically colored, the artist continues his line of critical statements.

In a symbolic opposition to Radya’s activity, but in unconditional ideological conjunction with him there were Moscow artists Kirill KTO and Pasha 183, both of whom started out more than 15 years ago as a graffiti writers. In contrast to Tima’s technically complex installations, works of Kirill and Pasha were largely spontaneous and therefore not as media-like and ambitious.

Kirill KTO had more existential and poetic work of textual nature, based on reflections of various personal and social processes, and sometimes relationship between them. His street comments could largely be seen as a motivational speech, an audience of which, however, was not always a casual viewer – sometimes his message was addressed to a specific person or just to himself.

Pasha 183 mostly worked in the style of street installations, first of which dated 2008. Until this moment Pasha mainly addressed everyday matters of existence in the city; in 2011 he created two politicized works: “To Incendiaries of Bridges” and “Truth to Truth”. In their turn, they underlined an anarchist and protest-like artist’s spirit that had been present in his works before but was never so obvious.

Hardly anyone of us now, having reached success, relationships, money, fame, is able to give up all of this. To burn the bridges and to destroy all your achievements for a new unknown, perhaps reckless and illogical life or death. This installation is dedicated to those who have gone beyond their own dusty corners and created a new world. To those who are able to deny themselves for the sake of a step forward6.

From the perspective of politicized content of works, one of the street series of artist Misha Most is also interesting. Having solid experience of graffiti activity and being the founder of the project No Future Forever and a member of one of the first graffiti crews CGS, he creates works of social and post-apocalyptic nature. His series of Constitution Live (2013–2014) in many ways is a logical extension of his graffiti practices, and correlates equally with folk and civil graffiti usually occurring in an unstable political situation.

In the political field, there is also team Partizaning whose participants call for self-organization and change in urban spaces through urban interventions, and, using their website as an open online platform, try to mobilize the spirit of protesting and illegal street art. However, given that Partizaning is not so much an art project as a phenomenon of socially engaged street art, one can note significant impact of popularization of these ideas among activists and street art artists recently having come out in the urban space. Above all, it concerns new and young personalities and teams, often balancing between art and activism7.

Several other activist artistic practices based not on the change but on the study of the city in terms of the democratization of its spaces were activated. For example, in Moscow, a number of projects related to environmental state of the city were active. Among them, there were guerrilla gardening practices, along with projects of studies of flora and fauna generated by the city, such as Urban Fauna Lab, members of which primarily focused on invasive species of plants and animals. For the most part, these initiatives appeared spontaneous and self-organized. One of the most striking examples of self-organization was the art group ZIP, members of which were active in the south of Russia since 2009. In informal manner inherent to them, in their hometown of Krasnodar, they organized the Institute of Contemporary Art, a residence, a cultural center, and a public art festival that have become a real catalyst for a developed artistic life there.

Regardless of the dominant political agenda, works of several other Russian street artists – Stas Dobry (b. 1985), Artem Filatov (b. 1991), Vova Chernyshev (born in 1992), Grisha (b. 1989) and 0331C – seem interesting and socially significant. However, from time to time, reflection on various processes taking place in their native city, district or yard can be traced throughout their work.

For example, the most exemplary product of such reflection was one of joint works You can apologize as always, but respect the wallS, created by street artists Stas Dobry and 0331C in 2011. With this gesture, they indicated, on the one hand, the problem of demolition of buildings in Moscow, and on the other hand, informed participants of extensive graffiti community about caring for the historic heritage. Later, in a few of their other collaborations the house became an animated character, asking for protection, fighting with the flood of new construction.

In most cases, the works of artist 0331C by its nature were the most expressive and ambitious. In some ways, they were an extension to the graffiti intentions of the artist, but each time became a new step in rethinking of this phenomenon. His works are interesting because of such a pronounced expression and “wild” energy, a daily practice of urban space habitation, sometimes inherent in a graffiti artist only.

In public spaces of Russian cities, mainly where monumental murals festivals were organized (Moscow, Yekaterinburg, Vyksa, Nizhny Novgorod, etc.) there were also a number of authors working mostly in an abstract and illustrative style – Alexey Luka (b. 1983), Petro (b. 1984), Vova Nootk (b. 1981), Dmitry Aske, Akue (b. 1986), Zmogk (b. 1979), Morik (b. 1982), Nikita Nomerz, groups of artists Zuk Club, 310 squad, ‘Vitae vyazi’ and many others. Their works were in many ways complementary to scene design of urban space, embellished it, and, as a rule, were outside any social discourse. They occurred more and more frequently, thereby indicating a trend of “europeanization”8 of Russian cities, with their city management seeking to create a unique image recognizable around the world.

This trend was somewhat contrasting to politicized grassroots street art practices, which manifested themselves illegally and existed without any funding. Swiftly rushing in public space, monumental murals are in no way representation of the interests of citizens, and are located on the side of the state and business, dividing the territory of the facades between themselves today and subsequently using them as advertising and propaganda billboards.

Nevertheless, there were exceptions even among these festivals. For example, Nizhniy Novgorod festival ” New City: Ancient”, organized by Artem Filatov and his associates in 2014–2016, had a very specific socially important mission – protection of heritage and architectural monuments, mostly wooden. Closely interacting with the residents of these homes and discussing with them the jobs to be created in the framework of the festival, the organizers used street art to a greater extent in order to attract attention to these homes and to the problem in general. This, in turn, shaped a unique approach to working with city surfaces – a more cautious one, not violating the existing ecosystem of the city. One could say that today this approach is a specific style of Nizhny Novgorod street art and forms a “movement” of socially responsible street art.

In the Urals, an authentic “movement” of street art can also be mentioned that is significantly impacted by Arseny Sergeev (b. 1966) and Naila Allahverdiyev (b. 1978), who organized a series of art projects in public spaces in Yekaterinburg in the beginning of the 2000s. The focus of these projects was made on media art, but in 2003 the curators ran a more traditional for street art format of mural art on the walls – “Long stories”, which became one of the most large-scale and systematic projects of this kind. Having existed until 2010, the festival later moved to Perm, where a “cultural revolution”9 occurred at the moment, expressed in an outburst of various kinds of cultural activities, in particular, in a large-scale public art program developed in the city’s public spaces.

It is important to note that for a long period Arseny and Nailia worked not only on organization of art festivals in Yekaterinburg (and later in Perm), but also on an educational program, within the framework of which renowned street artists were invited with master classes and lectures. This program was part of their school ArtPolitika, organized in Yekaterinburg in 2005. Over the years, some of now famous Yekaterinburg street artists were students of this program. Thanks to this systematic work, in today’s Yekaterinburg street art is not only developed as an illegal activity, but is also integrated into a number of institutional formats. For example, from time to time, Ural branch of the National Center for Contemporary Arts (NCCA) supports street art; since 2010, a large-scale street art festival Stenograffia operates; and in 2014 a gallery Sweater specializing exclusively in representing street art opened.

The products of such diverse and complex activities can be considered a strong Ural’s street art movement. The most outstanding representatives of this movement can be considered Tima Radya, Slava PTRK (b. 1990) and the art group Zlye. Vitya Fructy and Udmurt have an interesting approach to understanding of urban phenomena.

A special style can also be traced in St. Petersburg, where art activism is a predominant activity. This is confirmed not only with bright examples of actionist practices by already known artists and activists such as the group Voina and Peter Pavlensky, but also with a large community of artists of platform Chto Delat (“What is to be done?” in English)<sup>10</sup> comprising today not only a website and a newspaper, but also a school and even a house of culture. Since 2003, members of the team Chto Delat have periodically conducted certain actions in public space, representing both psychogeographic walks and urban performances. Regardless of these, but often in conjunction with them, there have also been other initiatives, such as, for example, Street University, which is a self-organized educational project, or street art team Gandhi, the female members of which are more focused on the issue of gender and social inequality.

- The first calls for the coming-out of artists in the streets could be heard in poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893–1930), public lectures/discussions by Ilya Zdanevich (1894–1975), Mikhail Matyushin (1861–1934), David Burliuk (1882–1967), Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935), Alexei Kruchenykh (1886–1968). The most integral vision of art “invasion” can be considered the decree No 1 “On the democratization of art” formulated in 1918 by a group of Russian Futurists, including, besides Vladimir Mayakovsky, David Burliuk and Vasily Kamensky (1884–1961). The first actual attempts at reclaiming public spaces by various artistic trends were linked to a greater extent to the celebrations to mark the anniversary of the October Revolution. Since 1918, a festive atmosphere in the style of easel painting had been created mainly in Petrograd (later Leningrad) and Moscow.

- Over the 1990s E.T.I. movement organized actions on the Red Square for freedom of speech and on the issue of parliamentary elections; Oleg Kulik (b. 1961) deliberately chose the image of an animal’s life to show horrific conditions of existence of the Russians. By building barricades in the centre of Moscow, Anatoly Osmolovsky (b. 1969) as a member of E.T.I. movement updated the practice of Situationists of the 1960s. Avdey Ter-Oganyan (b. 1961) and Oleg Mavromatti (b. 1965) later touched on the subject of religion and were prosecuted by the authorities for that. These and many other provocations on entirely diverse vital topics, from politics to religion, were the agenda of the day of modern life in Moscow in the 1990s. Sharp and radical actions marked the first step towards the return of informal activity on the streets of our cities.

- Institute for Media, Architecture and Design, founded in 2009.

- The right to the city is an idea and a slogan that was first proposed by Henri Lefebvre in his 1968 book Le Droit à la ville. Lefebvre summarizes the idea as a “demand… [for] a transformed and renewed access to urban life”. David Harvey described it as follows: “The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights”.

- One of the most important practices of understanding of the urban space is tagging and graffiti as practices of permanent interaction with the urban infrastructure. In many ways, this is why many of the contemporary manifestations of street art have their roots in the graffiti subculture that allowed them to open a new perspective on the city.

- Pasha 183 on the work “To Incendiaries of Bridges”. Artist Website: 183art.ru

- Such practices are covered a series of materials “New cheerful ones” on the project website: partizaning.org.

- The era of active transformation of public spaces was most pronounced in Moscow, where between 2011 and 2014 the so-called “cultural revolution”, which consisted in a humanization of the urban environment, was carried out. Changes were made with the active participation of the mayor S. Sobyanin and head of the Department of Culture S. Kapkov (resigned in 2014).

- “Cultural Revolution” in Perm started in autumn 2008 with the opening of the exhibition “Russian Povera” in the former River Station building, which was soon transformed into the Museum of Modern Art PERMM. Over the next 4.5 years a number of cultural programs was held in the city: from exhibitions, festivals, theatre performances to large-scale public art program and integrated project of design of the urban environment. With the departure of the governor Oleg Chirkunov in 2012, almost all the cultural programs were curtailed.

- The collective Chto Delat (What is to be done?) was founded in early 2003 in Petersburg by a workgroup of artists, critics, philosophers, and writers from St. Petersburg, Moscow, and Nizhny Novgorod with the goal of merging political theory, art, and activism. To find more on the projects of the platform, please check their website: chtodelat.org

Emma Arnold is a dual Canadian and British citizen who has lived and studied in Canada, Greece, Hungary, Norway, and Sweden. She is a cultural geographer with a background in environmental geography, environmental impact assessment, and environmental policy. She has previously worked as a policy analyst developing environmental legislation and regulation for the Canadian government. She is currently a doctoral research fellow at the Department of Sociology and Human Geography at the University of Oslo, where her research focusses on environmental aesthetics, graffiti and street art, and urban space.

Emma Arnold is a dual Canadian and British citizen who has lived and studied in Canada, Greece, Hungary, Norway, and Sweden. She is a cultural geographer with a background in environmental geography, environmental impact assessment, and environmental policy. She has previously worked as a policy analyst developing environmental legislation and regulation for the Canadian government. She is currently a doctoral research fellow at the Department of Sociology and Human Geography at the University of Oslo, where her research focusses on environmental aesthetics, graffiti and street art, and urban space.