Nuart Journal: Congratulations on getting your film almost to the point that we can all see it! We are curious about the background to this project and how this evolved into a feature-length documentary.

Daniel “Dusty” Albanese: I have been documenting street art for well over a decade. In 2013, I went to Paris, and I discovered Suriani’s work. He’s a Brazilian street artist who was living in Paris at the time. And he was doing these beautiful hand-painted larger than life drag queens from Ru Paul's Drag Race – which was much more underground at the time. We became friends while I was in Paris, and his work made me start thinking about queer representation and street art. I was thinking, why haven’t I seen more queer street art? Why don’t I know more about queer street art? It certainly made me think about the codes in art – Suriani was telling me that many people just saw them as big, beautiful women, they didn't necessarily know that they were drag queens. Queer artists speak to other queer people through their work through the codes and symbols that we recognise that others don’t, if it’s not an obvious symbol like a rainbow or something like that.

After that trip to Paris, I was buzzing. I found it fascinating, and I wanted to know more about it. Also, around that time, Homo Riot, an American artist, came through New York, and he put up much more aggressively homoerotic work thanSuriani. And so, then I thought about those two queer artists, and how different they were from one another in terms of their coding. One is much more aggressive and it’s very obvious to anyone that it is queer, and the other is coded for queer people to recognise. That was when I felt like maybe there’s something really interesting going on here. But the only thing I could really find on queer street art was this one art show that Jeremy Novy – a queer street artist – had put together years before and was composed mostly of the collection that he had been putting together of other people’s work. Other than that, there was nothing out there.

So, that’s what led me to start reaching out to queer identifying street artists and asking them to send me the names of any other queer artists they knew, and I started to build a database of everybody I could find around the world. That was the first step. I dug, I searched hashtags, I literally scraped the entire world for anything I could find. At this point, my database had probably about 300 entries. And that’s when I decided that this could be a book. Prior to this, I had been approached by a publisher, but I turned them down mostly because they wanted me to do another New York City street art book.

So originally this project was just going to be a book, but then I realised that I would have to travel around the world to research this topic. And I figured if I was going to do this, I wanted to do it on all levels. I had always wanted to make a film. So, I thought, I’m going to make a film and I’m going to do a book at the same time. And that was the genesis of the project. That was in 2013. The production itself began in 2017. And for all of those years, I reached out to artists around the world, talking to them, telling them about the project and what they could expect, making sure they were on board. And then I started my research in London, and I did a trip around Europe for about a month, then I kept working on the film over the years. I filmed in 16 cities across seven countries – including New York, Paris, London, Copenhagen, Rome, Montreal, Mexico City, and Los Angeles.

I believe you have a background in anthropology. Is your stance towards this project informed by this academic background and research training?

I studied anthropology as an undergraduate, and it was years later, when I started documenting street art and other subcultures that I was first asked to give a talk at a university. And it was the first time I had really thought about my work. I realised then that I was kind of doing a form of ‘outside the box’ anthropology. And then I met up with some former professors of mine who were excited that I had gone in this direction and had not taken the traditional academic route. So, yes, my work is definitely informed by anthropology. I think people who have a disposition for social science tend to have a curiosity about people. So, I approached this topic by asking, ‘what's going on here?’ I was trying not to bring too many of my preconceived ideas, but I was also fully aware that what I’m going to end up with was going to be informed by my perspective.

And I was always cataloguing – I had an index of every artist by medium and theme. I was really interested in questions like, ‘who‘s making political street art, feminist street art, animal rights street art?’ I was constantly categorising the street. And I was very curious to see patterns. So, at that level of really wanting to survey the scene, I wasn’t coming at this as a superfan, I was genuinely curious about what was happening. And when you observe a scene for long enough, you start to see patterns. And that, to me, was really interesting – for example, to watch how street art really starts to change as social media becomes an influence. It’s also interesting to see when politics comes into street art – I became aware that in the New York scene, politics was almost absent from street art in the 2010s. At that time, there was a real lack of political street art in NYC, whereas in most European cities, you’ll find a lot of political street art.

This was pre-Trump?

Once Trump comes in, it transformed. And you start to see a lot more political street art. But the Black Lives Matter movement, for example, had been going on for years. And I was shocked that I wasn’t seeing this reflected in street art until the pandemic. So, back then, I noticed that there was a lack of political street art in New York City. But now there’s much more.

In the last issue of Nuart Journal, we published a roundtable discussion of feminist queer graffiti and street art scholars. Until that point, we were pretty much working in parallel – we knew each of us existed, but there were few opportunities to connect. To what extent do you connect with queer academics working in this area?

That’s an interesting question. I’m aware of a lot of academics now. When I started surveying what was out there, I wanted to find out who else has written about this? What else is going on? Originally, I was reaching out to more academic-type people, particularly when I was researching the ancient aspect of graffiti, like Pompeii. But I found that a lot of the academics that I reached out to would often be like, ‘well, that's not exactly my area of expertise’. So, it felt like there was a lack of willingness among the academics to talk to me. I wasn’t sure if it was, ‘I don't know who you are’, or the territorialism of ‘this is my area’. I think that made me pull back a little bit.

When I first started making the film, I was interviewing street experts from the different cities I would go to. Not academics, but people who may play a similar role to me in different cities. But I was finding that when they were on camera, they were nervous to be forthright about the things that they would say much more clearly to me in a pub. And I think that if you have skin in the game, in the street art world, particularly the mural-world, you want to make sure you’re still invited to mural festivals and events. I think people get a little nervous about rocking the boat and there’s a lot of different gatekeepers. And I was challenging them by asking, ‘why haven't you photographed or written more about this?’

Originally, I cast a wide net to find artists. But I also collected every academic paper that was written about queer street art, and I continue to do that. It’s interesting to see how my research is now making an impact, while I am still trudging along making this film. I was much more guarded with my research in the beginning, because I wanted to make sure I got ahead of it. I didn’t want to just hand my research away to everybody. But I think there’s a lot more to be gained when people share and collaborate.

To what extent does the film cover queer histories of work on the streets?

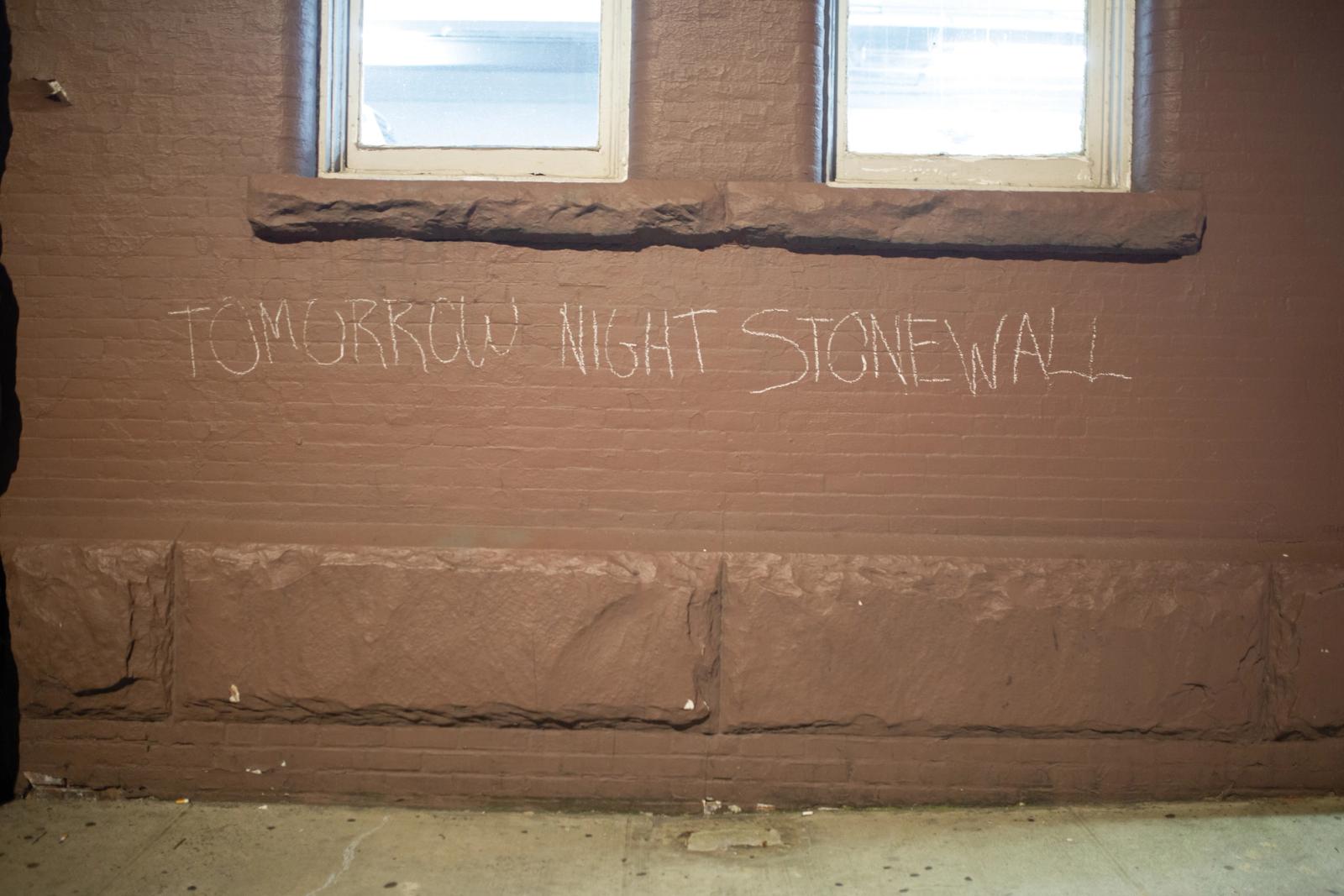

As I was interviewing people, particularly people that were around my age and older, they kept referencing Act Up and various sites. They kept referring to LGBT history and referencing past queer icons – Klaus Nomi, Judy Garland, and famous drag queens would pop up. This made me start thinking about history. I remember learning about feminist graffiti when I was in college, so that’s one of the places that I started to dig. One of the most amazing nights was when I was filming the Drag March in New York City on the 50th Anniversary of Stonewall, and I saw this guy chalking ‘Tomorrow Night Stonewall’ on the wall. And so, I asked him, ‘what are you doing?’ And he said, ‘Oh, I read this article, that on the night of the riots, teenagers chalked this on the wall, and I wanted to replicate it.’ I could not have set that up better if I paid someone to re-enact this scene.

That’s when I started to delve more into the history of queer street art. And to think about the fundamental connection between queer liberation and street art. They are both about taking public space and declaring your right to exist. They exist hand in hand and have a shared history because they have always worked together. Queer activists have always taken to the streets and used the streets as a way to communicate and organise – you had it with lesbian feminist graffiti, you had it with Act Up.

And when that Stonewall moment happened, that’s when I knew that I’d actually tapped into something that I think is incredibly important. When ‘Silence = Death’ came out, I was a young queer kid, just outside of New York City. But I saw that slogan on the news every night, it seeped into my home, it became something that everybody knew. So, it was an incredibly effective use of public space to communicate an activist message. Some of the most powerful street art activist campaigns have been done by queer collectives. And that, to me, is really a powerful history that I feel needs to be woven into the history of graffiti and street art more.

A lot of our visual activism now takes digital forms, even if it starts on the streets. How has social media impacted on queer street art?

I don’t know what the future holds. But you know, as social media platforms become more censored, we’re fighting an algorithm that you cannot beat. It’s different from the material focus that my generation had – we had zines we physically collected. When I was a kid, I would sneak into New York City and go from music shop to music shop, to see what was happening in the music scenes, and the punk scenes, until we got yelled at that we had to buy something and ran out the store. We learned about stuff by physically going out and finding each other. So, for me, it’s kind of my natural gear. This becomes so much more difficult when we communicate digitally. But we’ve had a lot of different ways to communicate that don’t rely on hashtags.

We wanted to ask you about your own history of visual activism. You were part of the Resistance is Female campaign and you also organised the Resistance is Queer phone booth takeover a few years back now. Are you still engaged with street-based visual activism? And is the film itself a form of queer visual activism?

Good question. I very quickly went from being an observer of street art to becoming an active part of the community. Resistance is Female was a collective campaign that happened soon after Trump came into office, and I did a piece for that. And at that time, I had been doing the research for the film, but I hadn’t started filming yet.

Abe Lincoln Jr., who was spearheading a lot of these campaigns, wanted to start one called Keep Fighting. Resistance is Queer, and Keep Fighting were a collaboration between the two of us. I wanted to take my images of queer activists and put them into the street, on phone booths, on this beautiful dying infrastructure. I also wanted to put art in places that you might not expect, to have these hidden little gems of activist art. I tried to put them in site specific places – I wanted to put them in places that were historically important. That’s what I was doing with Resistance is Queer, which were my own portraits from the Drag March and from various protests that had happened over the years. Then, during the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, I wanted to make sure that the art that referenced this wasn’t just murals. And so, along with Art in Ad Places, we came together, and they basically handed over the keys to the phone booths. I brought in half a dozen queer street artists from around the world and I had them each design a poster for Stonewall 50. And those were very much put in site specific places. Lésbica Feminista is a feminist lesbian from Brazil. Her piece was put by Henrietta Hudson’s, which is one of the last lesbian bars in New York City. Jeremy Novy did a Leather Daddy that was put by what is now the Whitney but was where the Piers were, where a lot of cruising used to occur, and also where the leather bars were. Suriani did a portrait of Marsha P. Johnson. We put her by the Christopher Street Piers where her body was found. So, each piece was part of our history, and they were physically put in the places that would reference this history. And I was proud of those little details, because I really wanted to celebrate our history and to do it in a way that was site specific. I did not direct the artists – I let them do whatever they wanted. And then we figured out the spots that matched their work. Everyone just magically did a piece that was like, ‘oh, this would be perfect here’.

Resistance is Queer, New York City, USA, 2019. Photographs ©Daniel “Dusty” Albanese.

Resistance is Queer, New York City, USA, 2019. Photographs ©Daniel “Dusty” Albanese. Resistance is Queer, New York City, USA, 2019. Photographs ©Daniel “Dusty” Albanese.

Resistance is Queer, New York City, USA, 2019. Photographs ©Daniel “Dusty” Albanese.

How unusual to work backwards to find the perfect places for the art, rather than the other way around. Was there any kind of QR coding or links so that people who didn’t know about queer history could find out what the work was doing in that place?

We didn’t use any brand or any hashtag or anything. We just let the image stand there on its own. I actually love the concept of using QR codes to break the wall and educate people. But we were just so bare bones. Just getting the printing done and getting the work installed without getting arrested was a challenge.

A couple of years ago I looked at the street art and graffiti that was part of the campaign for marriage equality in Australia – not just the pro-marriage equality pieces, but also the hate graffiti, and the paintbombing of pro-marriage equality art. The whole beautiful and ugly conversation – with no editing. One of the things I found was that the ways that people interact with visibly queer work on the street is often quite violent. So, when it does get defaced, the gouging is deep – as if somebody really means harm. Is this something you focus on in the film?

This is something I focussed on with every artist I interviewed because it was also something I kept observing. I kept observing that queer themed art (and religious themed art) would often get scratched out. But the violent way that queer themed work is defaced feels different – the commentary is different. It’s not just adding a moustache, it’s not that normal thing that happens to work that hits the street, when people add their own marks to it so that it comes alive again – of course art on the streets has a life of its own. But what I was noticing happening to queer themed work was very violent – it was an attack. And so that was something I asked artists about, because I was curious to know if they were also noticing this, and what their own experiences were. And most of the artists had experienced this. But this is something that I think shocks some people who aren’t paying attention, who don’t realise that there is even a queer street art movement – and that queer street art is often attacked.

Why don't people see this?

That’s a whole other question – why aren’t more people seeing queer street art? That was something I was very curious about, and it was one of the things that motivated me to start this project. It exists – there’s a history of queer street art. And there’s a lot of it around the world. I had to travel to go and find these artists, and I kept finding more and more of them. Before I would go to a new city, I would write to friends who were very knowledgeable about the local street art scenes and say, ‘hey, are you finding any queer street art?’ And the answer was usually, ‘No.’ And then you get off the plane and you walk down Brick Lane, and it would be everywhere. So why don't people see queer street art? Are they not seeing it because they are straight? Is it straight people? You have gatekeepers who may not recognise queer visual codes, who aren’t looking at it because they just don’t see it, and you also have the muralism that is eating the street art scene. I think a lot of people focus on murals, and they don’t really care about the wheat pastes or the smaller things. They’re just focused on the big wall down the road. And social media also plays a role in what people see.

What role does social media play?

People ask, ‘is this gonna get as much attention on social media? Is it gonna make me lose followers? Is it gonna get censored?’ I mean, my own accounts have been shadow banned and censored. This is a thing that queer street artists constantly deal with – being shadow banned, constantly being censored, their work is constantly taken down. That could cause people not to photograph it, because they are afraid that their own accounts are going to get shadow banned. And so, you have a silencing of queer artists through social media. This is a real problem. And many of the laws that are taking hold in the States right now have a parallel with the ‘community standards’ of Instagram and Facebook, which constantly censor our art. The content is the decision of a social media platform which can decide whose body is ‘female presenting’, who has ‘female presenting nipples’, what is a ‘female presenting nipple’, and so on. The algorithm decides how much fatty tissue is allowed around your nipple. I know drag queens who have had their pictures taken down, because they weigh more than the average. It’s ludicrous that you have a social media platform deciding the gender of bodies, and then censoring you on that account. In America, all humans can be shirtless, in public, in most States, but you can't be on social media. So that limits how people can express themselves publicly.

Social media is a serious issue for queer people – our work and our art is being censored. People couldn't put up tributes to Carolee Schneemann when she died, because Instagram kept taking them down. What does this do to erase our history of artists? This is something that’s chilling, and I don't know the way around it.

Instagram did invite me to their headquarters to be part of a roundtable about censorship. But I haven't seen any changes in the four years since that meeting. It felt tokenistic. Queer people are still having the hardest time communicating and talking to each other online. Yet, the far right is organising in ways that they never have before. Because these platforms have put way too much pressure on censoring us. OK, maybe we don't adhere to the ‘community standards’, but you can put stuff that’s so clearly neo-Nazi, or grossly offensive hateful content, but we can’t use the word ‘dyke’ in a post.

This is something I find really upsetting. Especially since a lot of the research for this project was based on social media – I was searching hashtags and finding a lot of artists this way. The upside is, in the wake of this project, a queer artistic community has formed, and these artists have found each other – they know each other now. But I think that these platforms need to be much more aware of the ramifications of what they’re doing because this has serious real-world effects. It used to be that if I searched hashtags like queer street art, Instagram would show me everything in chronological order. As a researcher, that’s the only way I could find everybody. So, if I checked every two weeks, using the queer street art hashtag, I could scroll down and recognise where I stopped last time, and see everything in chronological order. Now Instagram is using an algorithm in what it shows me. So how can I find people if they’re not already popular? And this again starts to sink people’s voices. Social media is such a powerful tool, and it has such potential for good. But I’m seeing that whittled away every day.

It sounds like the influence you’ve had in bringing people together has been palpable. Do you think queer street artists have become more visible on social media through your intervention?

Yes, I think so. When I started researching queer street artists on Instagram, I could scroll back and there were only 25 or 30 posts. Now you can scroll what seems like forever. The more people I found, led to more artists finding out about each other, and having a hashtag to coalesce around that could be used for all forms of queer street art – lesbian street art, gay street art, trans street art, and so on.

I see so much more queer-themed street art now than ever before. There’s definitely been an increase. But social media has affected street art in general, and the ways artists perform for social media. There’s a huge difference between how street art used to be and how it is now, in our cities. I was really surprised at how few times I took my camera out when I was walking around London. Because of hyper gentrification, a lot of hotspots are no longer hotspots – you used to find street art all over East London. Now, it’s like Berkeley. There’s less and less organic street art. But there are murals everywhere, and now most people see muralism as street art.

Is depressing that you’ve got to know exactly where to go to find the little pockets that still exist. I mean, if you got rid of Freeman Alley in New York City, there’s almost no street art left. It’s incredible. There are more street art photographers than there are street artists at this point. So, this has created social media bubbles in places like New York and London. If you’re watching from online, you think ‘oh, there's so much art!’ But then the tourists come to find all the art and they're baffled.

Previously, you’ve discussed queer depictions of the penis in public space but I’m not sure whether you also consider representations of vaginas in public space in the film? These seem far more rare – I’m thinking here of Carolina Falkholt’s mural scale vaginas.

I remember Carolina did a mural of a giant erect penis, and around the corner she painted a big vagina on a wall – but no one paid any attention to the vagina. To me that was interesting because people were up in arms about the dick and they were totally forgetting that there was a vagina around the corner. So, your question is interesting – I was really curious to understand why I didn’t find more erotic lesbian street art.

A lot of the women artists I interviewed said that they didn’t feel motivated to make this kind of work because they felt that women are already objectified so much in the public sphere, and they didn’t want to contribute to this. We were talking earlier about what happens to queer street art in public space, and they also really didn't like the idea of putting a woman’s body out there to be, for lack of a better word, manhandled by the public.

Also, even when I find a depiction of apparently ‘lesbian’ themes, I’m also always curious to know if this was made by a lesbian or a femme-identifying person, or whether it’s some kind of male fantasy? Once I found a sticker of Super Girl and Wonder Woman making out – and if someone put a gun to my head, I would probably say this was man made. But there are some examples of erotic lesbian work. Lésbica Feminista, the artist I talked about earlier, does erotic work that is really fascinating. She works with historic images, often classic paintings, and gives them a lesbian gaze. She’ll put an historic image of two women together in a way that gives a sense of lesbian eroticism and the lesbian attraction. There’s something so smart, and sexy, and beautiful about her work. It captures something beyond the quick eroticism that often happens in male homoerotic work, there’s just something deeper there that makes you stop and look at both pieces and think about what’s happening with those women.

Do you think that this level of coding is something that the ordinary straight person on the street is going to experience – a destabilisation or queering of the gaze? Or is this a visual pleasure that is just for queer audiences?

I honestly think some of this stuff is really just for us. But I don’t know. For instance, Jilly Ballistic, an artist based in New York, takes historic photographs, usually from World War I and World War II. And she isolates the women pictured from their backgrounds, so that they’re together. There’s a subtleness there, that some people could just be like, ‘oh, look, women with gas masks from World War I’. But when you have the ability to see, you can see these women are together. Certain generations of queer people, even today, had to try to find references for ourselves, especially if we grew up in a world where there were many examples of visible queerness of any type. So, we were often left to project queerness onto the people we could see in our world. I have had a lot of conversations with gay men about the glamorous women we could see ourselves reflected in, who were also fighting the patriarchy, the system that was stepping on all of us. But when I saw a woman fight back, I was like, that’s awesome. Because if she could fight back, then we could follow in her path and figure out how to navigate this world. And that’s why glamorous women like Joan Crawford and Bette Davis have been used to stand in for gay men. They’re just so over the top – Camille Paglia has described them as ‘female female impersonators’. So, the language and coding and the ways we read art is also a byproduct of an oppressive society. But this is also a gift. That is how we look at art. Artists use all sorts of codes – this isn’t unique to queer people. All art has codes, you should be able to deconstruct the visual language that’s being given to you and figure out what the artist is trying to tell you. And I think that everyone should bring this to every piece of art they’re looking at, because there’s something there that you can't just passively snap a picture of and walk on, you should sit with a piece to understand it.

Lésbica Feminista, New York City, USA, 2019. Photographs ©Daniel “Dusty” Albanese.

Lésbica Feminista, New York City, USA, 2019. Photographs ©Daniel “Dusty” Albanese. Lésbica Feminista, New York City, USA, 2019. Photographs ©Daniel “Dusty” Albanese.

Lésbica Feminista, New York City, USA, 2019. Photographs ©Daniel “Dusty” Albanese.Street art is so interesting, when you spend enough time observing people watching street art. It literally liberates art from the white walls of a gallery. Most people feel intimidated when they walk into a museum or gallery, they don't feel like they understand art. They’re scared of it – the white walls of the institution intimidate people. But on the street, when I’m shooting something, people want to see what I’m photographing. It’s not unusual to have a half a dozen people all having a conversation about what they think the piece represents. For me, the beautiful thing about street art is that people don’t feel afraid of it. They feel that they can talk about it, and maybe they're not so worried about having the wrong answer. Whereas a painting in a museum, they’re scared that they might have the wrong answer, even though there is no right answer – the wall plaque might tell you what it’s supposed to mean, but your own interaction with the work counts.

I think that’s the beauty of street art. That’s what I fell in love with – how random people could feel comfortable talking about art on the street with strangers. We need more of that in this world.

Different cultural contexts expose queer folk to different levels of risk in making work on the streets, particularly if it’s not legal or safe to be out. Is this something you were able to explore? If not, do you have plans to explore queer street art in other countries in the future?

Even though the pandemic cut things short, some could say it’s a blessing because when you’re filming you have the tendency to keep chasing the shiny object out in the water, and you could drown. Because there is always so much more to film. I really did want to continue my research – there absolutely could be a film just about South America. I really wanted to get to Australia. But I was fascinated by locations outside of more-or-less Western countries. Just because I wasn’t finding much online, doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. If I landed in the streets of Uganda right now, would I find any queer street art? Maybe I wouldn’t, maybe it’s not the safest way to communicate right now. Street art and graffiti isn’t always the best tool. It’s just one of the tools. So, each city is going to have a different way that queer activism will manifest. But I did have people write to me from Iran with examples. I would love to explore those areas, but there was no way I could do it on my tiny budget. But there is so much more to explore. This Herculean project that I’ve taken on is just the tip of an iceberg. And I really hope that if I don’t get to explore it myself, that other people keep looking. It’s funny when you start a project wondering, ‘is there enough to make a book or film about this?’ And then at the end, you're like, ‘oh, my God, there's like, way too much!’

I guess that’s one of the few silver linings of the pandemic – it made you stop filming?

Once I dealt with how frightening it was, the time I found myself with during the pandemic allowed me to start going through the footage. It was very helpful to get an idea of what I had collected. The pandemic did allow me to stop and breathe and kind of survey it and map it out.

With so much footage, you've probably got hundreds of possible arcs you could take in structuring the film. What have you come up with in terms of the driving structure?

The plan always was, in an ideal world, to produce a feature-length film, and also some shorts that focus on the artists, because the film can’t really explore all of the artists in a deep way. So eventually, I plan to do shorts of the artists, a book, and an exhibition. The footage was always shot with the idea that it’s a feature, but also we could produce shorts focused on the artists, like vignettes.

To support the production of Out In The Streets and to view a trailer, see the links below.

Out In The Streets:

Film Independent Page: filmindependent.org/programs/fiscal-sponsorship/out-in-the-streets/

Film website: queerstreetart.com

Trailer: youtu.be/Tj8lpzX-yQ4

Instagram: @queerstreetart

Daniel “Dusty” Albanese is the New York-based photographer and filmmaker behind the website TheDustyRebel. Shaped by his background in anthropology, he has built a worldwide following documenting the more marginal aspects of the urban landscape, as well as controversial artworks, and political protests. In 2017, he began production on his first feature-length documentary and book Out In The Streets.

In 2013, he gave a series of lectures on street photography at Wheaton College, Illinois, as part of their Evelyn Danzig Haas Visiting Artists Program. He has also been a recurring guest speaker for the City College of New York, as well as at Stanford University, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Adelphi, and MoMA PS1. Albanese has been interviewed for several street art documentaries such as, Janz In the Moment and Stick To It.

Albanese’s photography has been exhibited in many shows in NYC, such as the International Center of Photography’s ‘Occupy!’ and #ICPConcernedGlobal Images for Global Crisis. In 2019, his work was acquired by the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in NYC.