Figure 1: A group of trainspotters trespassing at Abercynon Shed in 1955. Photograph ©TLA, Neville Stead collection.

Figure 1: A group of trainspotters trespassing at Abercynon Shed in 1955. Photograph ©TLA, Neville Stead collection.

‘So much for these interfering bastard railway cops.’ (Dowie, 2011: 553)

I

As it passes under Pot Lane overbridge in rural Somerset, a Class 59 diesel-electric locomotive whistles its horn to the delight of Love Island's Chloe Burrows. This is Channel 4's Trainspotting with Francis Bourgeois. Shot from behind, the clip shows the pair enthusiastically observing the train through a spiked fence displaying a red sign that bears the warning; ‘Do not trespass on the Railway’ (see Figure 2). Francis Bourgeois has shot to fame after his videos went viral on social media. Ostensibly, Bourgeois is the archetypal trainspotter, maintaining an air of social awkwardness; he is male, obsessive, nerdy, and has an interest in trains that is, to all intents and purposes, pointless. Generally being held up in the public imagination as something of a national embarrassment and figure of derision, the trainspotter holds a unique place in the British psyche. Pot Lane itself presents the viewer with a particular romantic view of England as a rural idyll, a nation populated by law-abiding eccentrics, with only the occasional passing train to interrupt the tranquillity. The episode in question plays on the seeming incongruence of the characters of nerdy Francis Bourgeois placed alongside Chloe Burrows, a sex symbol from a reality television dating show, as the former introduces the latter to ‘the exhilarating world of trainspotting’ (Channel 4, 2022).

In his autobiography, the author and trainspotter Nicholas Whittaker describes how what was once a proud British pastime had, by the late twentieth century, become a national embarrassment. Originally published in 1995, by the time Whittaker was writing the popular image of the trainspotter, he had developed into that of ‘a gormless loner with dandruff and halitosis, a sad case obsessed by numbers, timetables, and signalling procedures. He has no interest in girls, and girls have no interest in him’ (Whittaker, 2015: XXIII). The railway historian Simon Bradley notes how trainspotters ‘were (and are) highly conspicuous on their platform ends, and could be (and are) jeered and gestured at from the safety of a carriage seat: dowdy-looking misfits to the public eye, pointlessly engaged in a project with no cultural, aesthetic or monetary value.’ He goes on to note how the words trainspotting and anorak, a garment closely associated with the subculture, entered the Oxford English Dictionary in the eighties as derogatory terms denoting boring obsessives (Bradley, 2016: 530–531).

So, considering the way in which trainspotters have been viewed by the public over the past few decades – as straight-laced oddballs, with their pedantic obsession, the observation of the mundane, and note keeping – viewers might be forgiven for believing that the portrayal of trainspotters amenably adhering to admonitions against trespassing on the railways is an accurate depiction. In the immediate post-war period however, trainspotting in Britain was associated with lawlessness to the extent that the subculture became the target of a moral panic in the press, and laws were even introduced in an attempt to curb the activity. The author Andrew Martin explains that, at one time, a trainspotter could be considered ‘hard’;

[…] spotters didn’t wait for the trains to come to them; they went to the trains. Engine sheds were ‘bunked’; that is furtively invaded. A good deal of bravery was required [this was] a Beano comic world of scruffy boys inventing ‘dodges’, sneaking through holes in fences, being chased by red-faced adults in official uniforms. Even when not bunking the spotter was at large, perhaps travelling – by train of course – to a bunk (Martin in forward to Whittaker, 2015: XI–XII).

In stark contrast to the uncool image of the anorak-clad loner whose interests are restricted to the end of the railway platform they inhabit, from the 1940s up to the 1960s trainspotters were frequently depicted as marauding bands of youths intent on overrunning Britain’s railways. In short, the trainspotter, that most peculiarly British of characters, is a social construct the same as any other. If the phenomenon of trainspotting has largely been ignored by academia and has been the subject of little historical enquiry, then the transgressive dimension of the subculture has been virtually invisible. In the pages that follow I therefore intend to bring the deviant character of early trainspotting to the light of contemporary scholarship, and to show that not only has trespassing been a common feature of trainspotting – and its more deviant manifestation – but also to suggest that it has even been one of its essential defining elements.

In the first section I discuss the portrayal of trainspotting as depicted in the children’s comic Acne at the close of the twentieth century. The disparaging images represented in this comic rely on recognisable tropes that have come to form the stereotype we have of the trainspotter today. Whilst the comic’s portrayal provides clues as to why the trainspotter came to inhabit the position it does in popular culture, it also hints at how that image has evolved. Rather than a romantic evocation of more innocent times, I suggest that the image of the steam engine is used in this particular comic as an allusion to a history of deviance. This history relates to a specific period that runs from the 1940s, when trainspotting became hugely popular in Britain, to its steady decline following the end of steam traction on British Railways in 1968. This time period is important because it was when the notion of trainspotting and the idea of the trainspotter was first constructed. I then discuss the manifestation of trespass by youths in the post-war era and argue that it was in fact an integral element in the formation and performance of trainspotting culture. As evidenced in numerous autobiographies covering the period, trespass was an exhilarating practice that pushed the boundaries of acceptable child’s play. The less obvious phenomena of graffiti and coin pressing are also considered as material expressions of the practice of trespass. Using ethnographic research on contemporary graffiti, I also suggest a reason for the use of trespass within the trainspotting culture. In the final chapter I explain how a moral panic arose in the British press around trainspotting, and the engagement and reaction of various relevant institutions with it. I also reject the previous scholarship on trainspotting which downplays the importance of trespassing within trainspotting culture, including the response to it in the press, and the official and legal attempts to restrict the activity.

II

In his history of the railways in Britain, Bradley highlights a one-off comic character named Timothy Potter who featured in the Viz, ‘that bellwether of 1980s popular culture’, as an archetype of the trainspotter. ‘Bespectacled, acne-dappled and dressed as if by his mother, myopic Timothy is too hopeless to even cut it as a number-collector’ (Bradley, 2016: 530). Just a few years later, at the start of the decade in which Nicholas Whittaker’s book was first published, the comic Acne was launched. The publication regularly featured trainspotters on its pages. In issue ten of the magazine, the spectacle-wearing, acne-covered, and anorak-clad Borin Norman introduces another character to his favourite pastime of trainspotting. He enthusiastically explains that it is possible to ‘spend countless hours collecting train numbers!’ After eight hours of doing so his acquaintance is left comatose and when the doctor arrives he declares him dead; ‘Looks like he died of boredom’ is the diagnosis. (Acne, No. 10, 1992) The obvious similarities between the two characters can be read as evidence of a clearly defined image of the trainspotter having cemented itself in the popular imagination.

But just who was perceived to approximate this caricature of the trainspotter? The answer to this can perhaps be found in another edition of Acne published later the same year. Issue eighteen contained a guide titled ‘how to spot the school geek’. A pair of cartoon figures are shown above a list of traits that mark them out. Whilst the hypothetical female character is derided in misogynistic terms, her male counterpart faces opprobrium for pursuing ‘hobbies like trainspotting’. He is illustrated sporting a broken pair of glasses, dressed in a hand-me-down school uniform from the seventies, and, once-again, covered in spots. The guide informs the reader that he ‘lives in a rundown council house’ whilst ‘his parents are toerags and don’t give a toss’. He can also be recognised by his unhealthy complexion and lack of interest in the opposite sex. The feature is overtly classist; here working-class children are ‘revolting’ due to their cultural interests, apparent social habits and, not least, their poverty. (Acne, No. 18, 1992) Once again, the representation of this trainspotting geek closely resembled the aforementioned depictions.

Nicholas Whittaker’s attempt to deconstruct this stereotypical image falls short with his sophomoric suggestion that with a shift in social attitudes towards racism, sexism, and homophobia, the trainspotter became an alternative target for vilification (Whittaker, 2015: XXII–XXIII). Essentially, a collateral victim in the fight against prejudice and bigotry. Likewise Carter references the former’s argument when claiming the trainspotter has been stigmatised as ‘British popular culture’s prime idiot’ (Carter, 2014: 96). In fact, it is the perceived class associations of trainspotting which I believe accounts for the disparaging stereotypes that have been built around it. Carter argues that by the mid-fifties the demographic composition of trainspotting had already begun to become less working-class and ‘familiar middle-class cultural forms soon emerged’ (Carter, 2014: 100). However, as the previous example from Acne demonstrates, even decades later trainspotting had not entirely shed its working-class associations.

From its inception in the early nineties, Acne ran a regular strip called Train Spotters by the gifted cartoonist Tony Wiles. It featured a nerdy trio of sexually-frustrated teenaged spotters. The first issue of the comic introduced the characters in stereotypical fashion afflicted with pimples, donning prescription glasses, and boring anyone they come into contact with. The strip ends with the gormless friends alternatively being mangled in some railway machinery, getting radiation poisoning from a passing nuclear train, and receiving a violent reaction from a woman waiting on the platform in response to an ill-judged sexual advance. (Acne, No. 1, 1991) The following month’s edition saw the Train Spotters return, this time getting themselves stuck on a delayed train waiting for a locomotive replacement. Subject to their obsessional discussion of the minutiae of technical matters related to the train, a fellow passenger is left exasperated by these ‘irritating nerds!’ Eventually the train is involved in a crash leaving the four passengers hospitalised, and the irate passenger once again stuck between the obsessive bores (Acne, No. 2, 1991).

However, in issue six of the comic the friends participate in behaviour that seems to contradict the established stereotype. Namely, the trio trespass into a ‘shunting yard’ and locate a steam locomotive. Unfortunately, the hapless trainspotters come to a customarily sticky end when the engine goes chugging over them (Acne, No. 6, 1992). Although they are usually depicted spotting contemporary locomotives, this was not the only occasion in which Tony Wiles used the image of a steam engine in the strip. Another episode showed a dream sequence in which a ghost train headed by a steam loco, the Flying Dutchman, pulls the spotters back in time as they gawp at steam engines of the past through the carriage window (Acne, No. 4, 1991). Finally, in a Christmas special of the strip, Santa Claus magically gifts a steam locomotive to one of the trainspotters which, predictably enough, runs him down (Acne, No. 5, 1991). Whilst in all of these examples the trainspotters remain ‘spotty nerds’, it is also clear that the steam engine initiates the appearance of a fantasy realm within the make-believe world of the strip itself (Acne, No. 6, 1992). The steam locomotive functions as a magical device signifying the ghost of trainspotting’s past. A past in which the standard rules of play are turned on their head. Take for example the Train Spotters' antics as the ‘Guardian Anoraks’ when they take it upon themselves to enforce a railway notice asking passengers not to flush the train’s toilet while in the station (Acne, No. 8, 1992). The sequence from Acne No. 6 in which the three trainspotters trespass onto the railway utterly contradicts this image of the boring nerd with a penchant for obeying the most trifling of rules and, in its use of the steam engine, hints at an alternative version of the trainspotter.

On the face of it, the Acne comic utilised the standard gamut of disparaging tropes to poke fun at the idea of trainspotting. As an example of the contemporary image of trainspotting that Nicholas Whittaker referred to in his account, Acne’s rendering was fairly typical. This was a cultural moment in which the image of the trainspotter had been firmly cemented as that of the archetypal nerd and general figure of ridicule in British popular culture. From my own research I have concluded that trainspotting seems to have garnered this stigma through its perceived working-class associations, which were themselves a hangover from an earlier iteration of trainspotting (Chambers, 2022). Furthermore, the cartoonist Tony Wiles uses the steam engine in the Train Spotters strip as a way to allude to an historical trainspotter that contradicts the image of the modern one. In fact, the reference to deviancy I have drawn from his use of the steam locomotive can be traced back to the forties and largely relies on the act of trespass that had been associated with the subculture.

III

In the Train Spotters strip the steam engine is a visual device that takes the characters into a fantasy world within the make-believe one of the comic. When they appear, the steam locomotives allow for a situation in which the rigid stereotype of the trainspotter can be transgressed. This may come about magically or in a dream state, but it is one that harks back to the past. Indeed, the transgression of the child into the authority of the adult world was an ever present element of trainspotting, particularly in its heyday of steam traction on British Railways. ‘Bunking’ was the term used by trainspotters to describe the practice of trespassing into engine sheds. Calling themselves ‘gricers’, this was an integral element of the subculture for many devotees, and a point of pride to the extent that it was even the preferred method of collecting locomotives for some. In December of 1964, the young trainspotter Grant Dowie and a friend visited shed 5A Crew North. Having been warned that they risked being ‘chucked into the cop shop and then slightly later – fined for trespassing’, the pair nevertheless illicitly circumvented a ‘twelve foot high boundary fence of iron railings’.

This was done despite the fact that they did have a permit to visit. Once inside, Dowie recalls seeing the names Lester Piggott and Uncle Bimbo graffitied on a steam locomotive suggesting other trainspotters had applied the same method of entry (Dowie, 2011: 373–374).

Part of the allure of trainspotting for some youths in the post-war period was certainly the excitement of transgression. For Whittaker ‘trespassing had always been a sport, but only as long as there was a danger of being caught’ (Whittaker, 2015: 142–143). Indeed ‘stake-outs and evasion were all part of the sport’ (Whittaker, 2015: 25). Recalling his heightened senses the first time he bunked a shed, he tells how ‘we stood there on the threshold, like mischievous elves in a giant’s lair. Leaning against the wall were huge spanners, as long as our legs. I had never trespassed like this before. Thrilled yet wary, our ears were cocked to a corrupted silence punctuated by the hiss of steam…’ (Whittaker, 2015: 9). Many trainspotters relished the challenge of bunking sheds in which they were not welcome. Gateshead, to take one example, ‘had a reputation for being difficult to crack’, meaning that access was difficult and security was known to be tight. Although this did not discourage a determined James Alexander when he visited as a twelve year old in the early sixties, as told in his autobiographical account of trainspotting;

[…] we knew there was no point in trying to walk in the front entrance but the entrance to the yard is a short distance from Gateshead East Station, so we walked down the line from there and hid by the side of a small repair shop then into the yard behind a slow moving V2 backing down to the shed […] (Alexander, 2018: 121)

The rapid rise in popularity of trainspotting in Britain from the mid-twentieth century relied on the increasing availability of leisure time and the relative affluence of youths in the post-war period (Chambers, 2022). One product designed for this new market were the shed directories which provided information on the whereabouts of locomotive sheds across the country. Nicknamed the Bunkers Bible, the publication produced by the Ian Allan publishing group was careful to disassociate itself from any perceived encouragement to trespass (Whittaker, 2015: 83). Concerned about how their publications were being used, or at least how they were perceived to be being used, early on publishers included warnings abrogating themselves of responsibility for trespass. A 1947 edition of The British Locomotive Shed Directory declared, in block capitals, that ‘IT IN NO WAY GIVES AUTHORITY TO ENTER THESE PLACES’ further cautioning that ‘unauthorised visits, and trespassing on the railway not only render the offenders liable to prosecution […] and result in the facilities being offered to rail enthusiasts being curtailed or suspended’ (Grimsley, 1947: 4). The shed directories were useful to trainspotters precisely because they gave directions to places that were private and inaccessible to the public. Alex Scott recalls using one of these publications to trespass on railway property in the mid-sixties. ‘Directory in hand, I was going to bunk one of the great sheds, 50A.’ Here he is referring to York shed in which, unfortunately, he was caught by the shed foreman and told, in no uncertain terms, to ‘… off’! Not wishing to receive the same reception as he arrived at Darlington station at 2 am later that same night, Scott made sure to hide the compromising shed directory from the prying eyes of the policeman closely observing him at the ticket barrier (Scott, 1999: 138–139).

Aside from autobiographical accounts published, at a much later date, in the form of stand-alone memoirs or on the pages of enthusiasts’ magazines, trainspotters at the time did in fact leave material evidence of their trespassing. This generally came in the form of photographs of locomotives produced for private consumption. However, while not as common, the use of graffiti was a technique utilised by some trainspotters as a very public display of trespass. Figure 4 shows a withdrawn 4-6-0 King Class in the foreground waiting to be cut up at Swindon sometime between 1962 and 1963. What is immediately noticeable about the image is the graffiti painted on the boiler and chimney. The names Jackie, Les, and Bumbal John have been tagged onto the locomotive in white paint, the latter underlined with a stylised arrow. Looking closely at the photograph, the locomotive in the background also has some indecipherable graffiti written on it. This graffiti was almost certainly produced by trainspotters who would have gained access to the engines through the works.

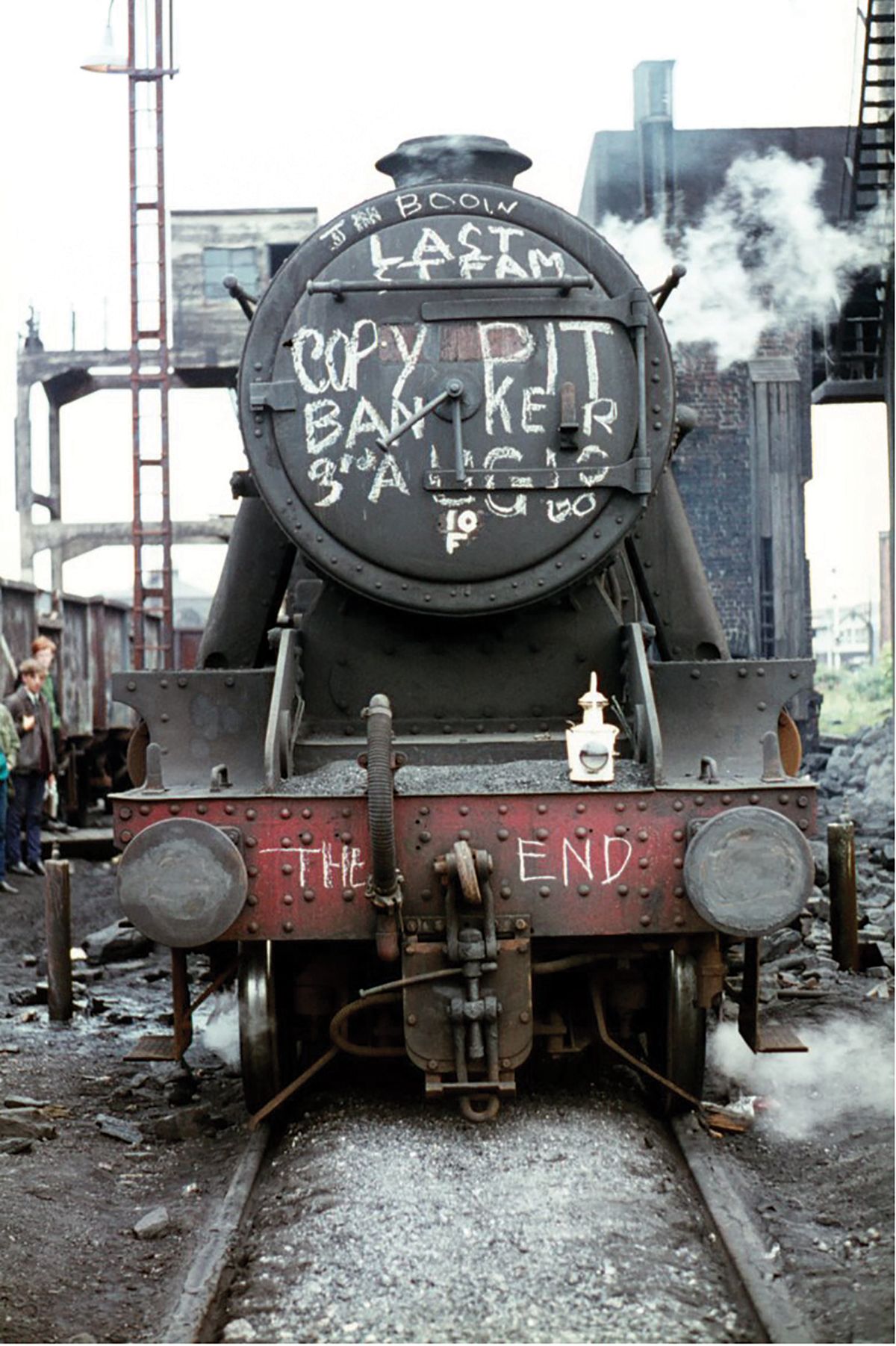

Such examples were not just casually painted onto condemned locos but could be produced as an act of commemoration. One former trainspotter related to me how a friend of his would bunk sheds in anticipation of the last steam running out of them and paint his name on them, among other things, as a final farewell on their last day (see Figure 5). Graffiti was produced by trainspotters particularly as a commemorative device to lament the closure of lines and, ultimately, the end of steam on British Railways. Fairly typical graffiti repeated in different examples include the slogans ‘steam supreme’, ‘steam is king’, ‘for steam there’s no reprieve’, and the poetic ‘steam forever, diesels never’. Other graffiti might include cartoon characters, references to popular television programmes and, of course, anti-Beeching sentiments (Chambers, 2022). Richard Beeching was the author of the 1960s reports that became known as the Beeching Axe, which advocated the closure of vast swathes of the railways and the complete withdrawal of steam on British Railways. A keen-eyed reader may have noticed the logo of The Saint chalked onto a 4-6-2 Battle of Britain class in Figure 3. Whittaker recalls the programme being a favourite of his and it is fairly typical of the televisual references that trainspotters would make (Whittaker, 2015: 40). Indeed, it is also interesting to note that similar imagery, such as that of New York graffiti artist Stay High 149’s now iconic adaptation of The Saint logo, was being used almost concurrently. Perhaps such details point to analogous cultural impulses being expressed by these railway-based subcultures, albeit completely independent of each other. Aside from being decorative, sentimental, or used as a form of protest, graffiti could have a more functional use too. In his memoir of trainspotting during the fifties and sixties, Forget the Anorak: What Trainspotting Was Really Like, Michael Harvey includes a photograph of a Black Five 4-6-0 locomotive onto which he has chalked its number 45038 (Harvey, 2017). As the era of steam came to a close on British Railways, locomotives would often have their name and number plates removed or stolen as mementos. As this particular Black Five has its smokebox number plate missing, Harvey left his graffiti for the benefit of any other trainspotters wishing to identify it. In fact, this is not the only example of graffiti documented in Harvey’s book. He relates a game he developed amongst his fellow trainspotters in which they would bunk into a local engine shed to graffiti surreal names onto the side of locomotives, some of which would then go into service bearing their new sobriquets as a conspicuous signifier of trespass (Harvey, 2017: 57). Harvey goes on to conclude that ‘I suppose we could be classed as being the original graffiti artists’ (Harvey, 2017: 87).

This may be a good juncture to pause and reflect on just why it was that trainspotters trespassed. Part of the answer can perhaps be found by comparing trainspotting with a railway based subculture that came after it. Writing about the modern graffiti movement in London and New York at the turn of the twenty-first century, Nancy Macdonald rejected the notion that it should be understood as a working-class subculture. Instead, she proposed that graffiti functioned as a tool for constructing masculinity (Macdonald, 2002: 94–96). Macdonald focused on the act of doing graffiti and what it revealed about those male participants. She argued that ‘[graffiti] writers confront risk and danger and achieve, through this, the defining elements of their masculine identities; resilience, bravery, and fortitude’ (Macdonald, 2002: 101). Indeed, Carter speculates that through the sixties trainspotting’s ranks were steadily depleted ‘as older hormone-driven train spotters yielded to girls’ softer charms’ (Carter, 2014: 269). In this framing, trainspotting and its associated acts of trespass, are gendered as a masculine activity that adolescent boys undertook as a rite-of-passage into manhood. Michael Harvey affirms this writing that girls ‘were kept completely separate from trainspotting, which was our life’ (Harvey, 2017: 25). He goes on to recount a particular trip during the late fifties in order to ‘give an indication of the incidents and, at times, dangers that teenagers experienced’. The excursion to the West Midlands was undertaken by ten schoolboys from Portsmouth who, after spending their first night in the cells of a Wolverhampton police station, managed to bunk more than a dozen sites over the course of three days. Harvey explains that;

Above all, they enjoyed the freedom and spirit of adventure which every trainspotting trip brought. An application for engine shed permits should have been a priority on any such trip, but official permits were only used infrequently, and when they were obtained no one bothered to produce them at depots unless they were asked for! This trip was one of those undertaken without permits (Harvey, 2017: 41–44).

Phil Mathison, the author of an account of trainspotting as a twelve-year-old in the sixties, describes his pursuit of numbers in terms of a rite-of-passage; as his peers were not yet mature enough to accompany him on spotting trips his ‘early outings were with older, more committed spotters’ (Mathison, 2006: 25).

However, what is interesting to note is that, unlike graffiti writers, trainspotters have often been reticent to fully embrace ownership of their particular history of deviance. Indeed it is usually brushed off as wholesome fun that was to be had in more simple times. While Harvey concedes that ‘the illegal ‘bunking’ of British Railways engine sheds, workshops, and other such installations […] is what helped to make the hobby both challenging and fulfilling’ (Harvey, 2017: 1–2), it was, nevertheless, a ‘harmless hobby’ (Harvey, 2017: 44). For James Alexander his trainspotting days were ‘a time of innocence’ (Alexander, 2018: 8), while for Phil Mathison, despite being ‘always on the wrong side of the law’, he describes it as ‘not only a steamier age, but also a more civil one’ (Mathison, 2006: 16 & 81). Perhaps, as I have previously suggested (Chambers, 2022), this narrative may, to some extent at least, be down to a process of schismogenesis whereby spotters retrospectively internalised their behaviours as good, or at least innocent, in contrast to that of the later graffiti writer. Indeed, Michael Harvey suggests as much when contrasting the ‘disgraceful defacings of today’ with ‘our actions in the 1960s [that] were never intended to deface or cause too much hardship to anyone’ (Harvey, 2017: 87).

IV

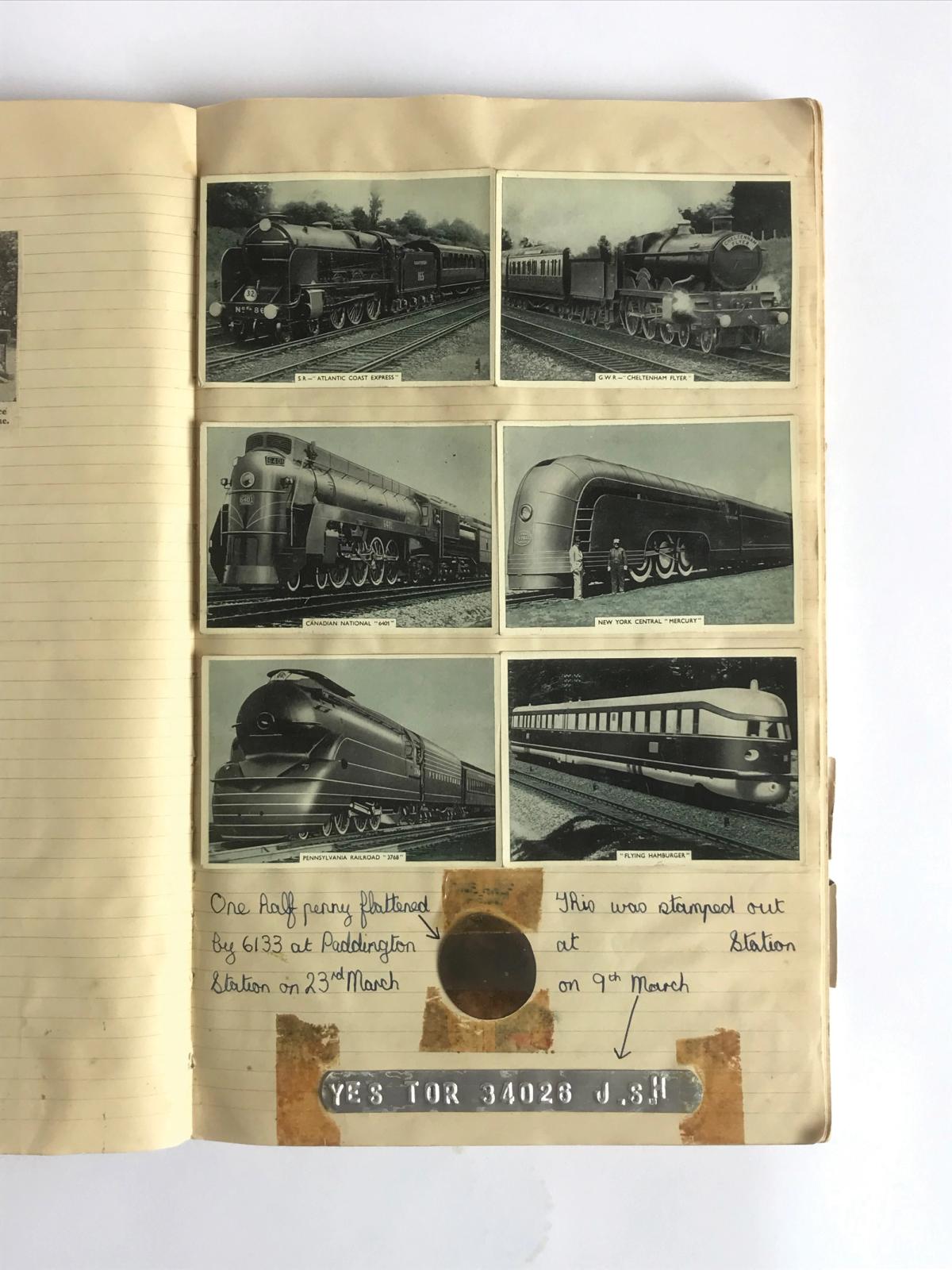

While graffiti may have noticeably advertised the act of trespass after the event, other mementos were also created by trainspotters. For instance, whilst waiting for the next locomotive to pass by, spotters would sometimes trespass onto the railway line to lay down a coin in order for it to be squashed by the next oncoming train. Stewart Warrington recalls that ‘we often placed pennies on the line to see them flattened by the train’, and even includes an image of one such example (Warrington, 2016: 16). A scrapbook kept by one young London trainspotter during the fifties has, in between carefully placed locomotive ephemera, a coin taped on a page with an annotation labelling it as ‘one half penny flattened by 6133 at Paddington station on 23rd March’ (see Figure 6). The locomotive in question, known as a Prairie, was used for hauling both passenger and freight trains. Not a particularly glamorous engine, the coin was presumably collected as a way to pass the time, rather than a memento of an impressive loco. And yet, the item was prized enough to be carefully saved, labelled, and taped into the journal by its owner. Positioned alongside other railway keepsakes, the pressed coin represented more than just a Prairie, it symbolised the act of trespass that was integral to the experience of trainspotting itself. As trainspotting took off in the forties, such occurrences were not treated lightly and increasingly came to be viewed as a problem by the authorities. In the late forties, the Midland Counties Tribune obviously found one such incident newsworthy enough when it reported on two children who had been arrested for trespass while out ‘train numbering’ after having placed coins on the line through Nuneaton (Railway Trespass, 1949: 4).

In fact the Midland Counties Tribune was feeding into a wider media phenomenon that Carter claims was, at least in part, a reaction to bunking (Carter, 2008: 100). In my own research I have found that press reporting of trainspotting in the post-war period did indeed match the classic model of a moral panic as outlined by Stanley Cohen in his seminal Folk Devils and Moral Panics (Chambers, 2022). The anxiety in the popular press around trainspotting began with a notorious mass trespass incident at Tamworth station in 1944. Reporting on a group of children who appeared before the local court on a charge of trespass, the Tamworth Herald noted that they had been arrested after having ‘placed coins to be crushed by passing trains and collected later as souvenirs’ (Tamworth Herald, 1944: 3). However, the fine they received clearly did not serve as a deterrent to other trainspotters and by 1948 Tamworth became the first station to officially ban spotters from its premises (Bradley, 2016: 522). Tamworth was just the beginning though, as the press began to regularly report on a game of cat-and-mouse played out on the nation’s platforms whereby bans would be alternatively enforced and then lifted in the hope of encouraging good behaviour.

Seeping into the folk memory of the subculture, Tamworth became a notorious event amongst trainspotters with the story being retold decades later (Whittaker, 2016: 57). Mirroring the hyperbole of the press, tales of such bans were mythologised and built into much more menacing propositions. In 1957, spotters were barred from Grantham station as the hundreds of boys and girls who were described as congregating there in the press were seen to ‘cause trouble and not only endanger their own lives but those of other people’ (Boston Guardian, 1957: 6). When Stewart Warrington visited the station two years later he took appropriate action; ‘On hearing that trainspotting at the station was punishable by death (things were exaggerated in those days by fellow spotters) we positioned ourselves north of the station’ (Warrington, 2016: 17). However, if the station was out of bounds then there was always the local shed, the allure of which proved too much for some spotters to resist. One such culprit, Ronald Edmunds, was brought before Grantham court on a charge of trespass and fined £1 after being caught collecting numbers in the shed in question. (The Grantham Journal, 1961: 16)

In reaction to the moral panic being played out on the pages of the nation’s press, relevant institutions felt the need to take action. The publisher Ian Allan, the most important commercial producer for the trainspotting market, certainly felt the need to protect their revenue by taking a more interventionist approach toward shaping the behaviour of their consumers. In direct response to the press reports of the events at Tamworth, Ian Allan founded a Locospotters Club. In his autobiography he explained that the idea behind the club was ‘to indoctrinate a code of good behaviour; all applicants for membership had to sign a declaration that they would not trespass on railway property’ (Allan, 1992: 19). Just how successful Allan’s attempts actually were in preventing trespassing is doubtful as the many subsequent newspaper reports on the crime seem to attest. Indeed, Whittaker ponders ‘how many club members kept to a rule that would have destroyed half the fun of trainspotting’ (Whittaker, 2015: 58). The Locospotters Club was not the only choice for trainspotters who could choose from a range of clubs and societies that organised trips. Many of these were less fussy about gaining permission to enter railway property.

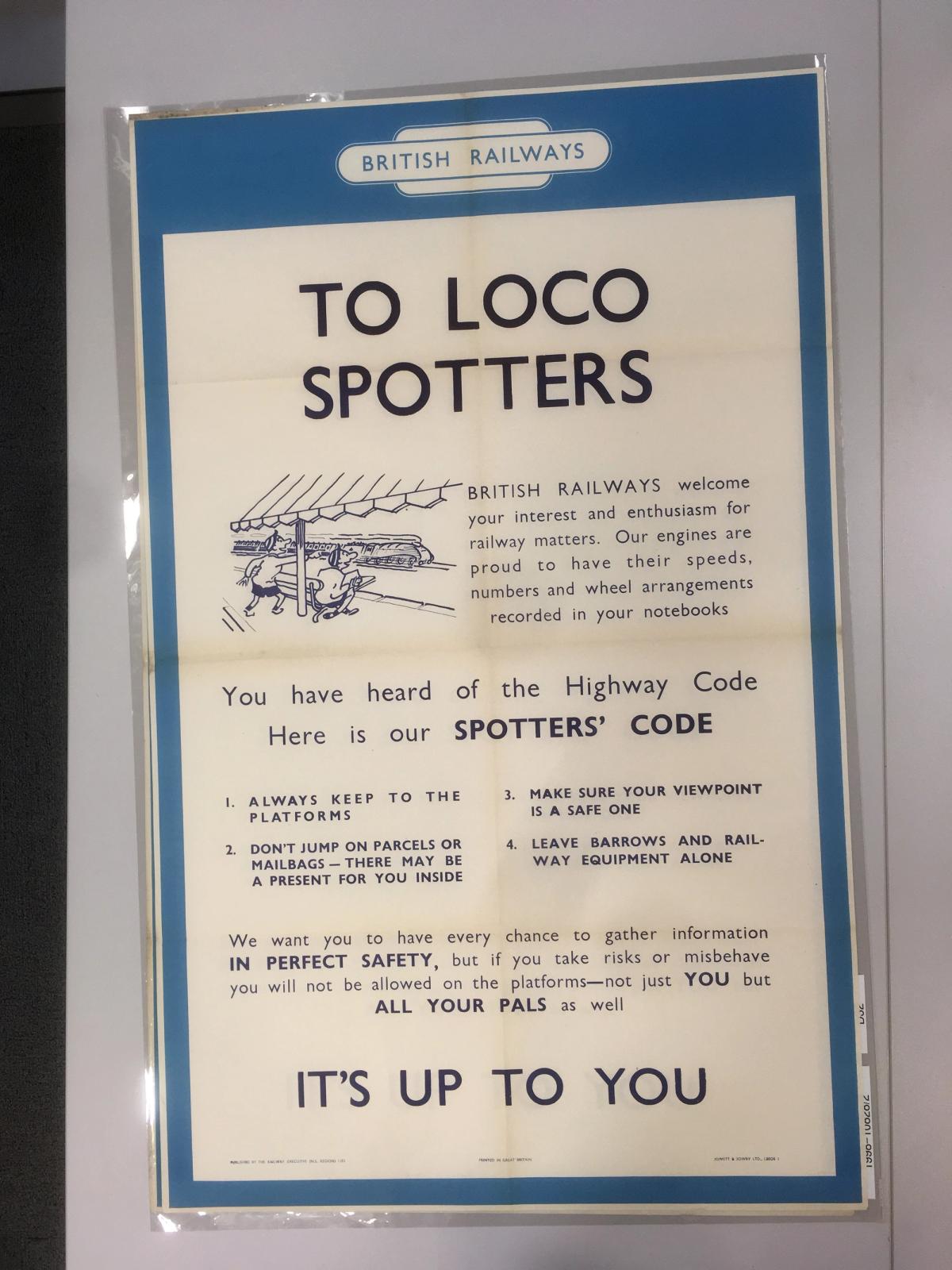

Meanwhile, British Railways launched its own initiative to cajole trainspotters into obeying the law. In November 1954, the organisation distributed five thousand posters displaying its own Spotters’ Code (see Figure 7). The campaign was initially claimed as a success with a British Railways spokesperson telling reporters that the Code had achieved ‘excellent results’ (Halifax Daily Courier and Guardian, 1954: 6). The front page of the Leicester Evening Mail featured a photograph of nine-year-old trainspotter Glynn Winfield reading a copy of the poster on display at Leicester London Road station. However, a year into the campaign, it was reported that the station master felt the Code was having little impact, with trainspotters continuing to trespass (Leicester Evening Mail, 1955: 1). More localised campaigns were also trialled such as that launched in Liverpool in 1960 aimed at children living near, what the Echo dubbed, Missile Alley. In appealing against ‘hooliganism and trespass’ British Railways were keen not ‘to stop children’s genuine interest in railways’ with their Code offering ‘points of advice expressly to train spotters’ (Liverpool Echo and Evening Express, 1960: 7). Aside from public campaigns, British Railways also invested in preventative measures including new fencing and hostile architecture such as that at Bath Road shed, rebuilt in the sixties, ‘with unwelcome visitors factored into the design’ (Whittaker, 2015: 51).

The transport writer Christian Wolmar notes that from their inception, rules, regulations, and policing have been a prominent feature of Britain’s railways (Wolmar, 2008: 49). Indeed, Grant Dowie’s irreverent account of a week’s trainspotting across the London Midland region includes numerous clashes with the railway authorities leading him to declare to his readers that ‘I hate COPS. Get the picture. Right, you've been told’ (Dowie, 2011, 59). In 1949 ‘a Newcastle youth’, seventeen-year-old Keith Robinson, was arrested and charged with trespassing in a local shed. Baffled at what motivated the young trainspotter, the magistrate asked Detective Inspector Wood why exactly Robinson had been collecting engine numbers? ‘It's a craze among boys at present. I think there is actually a society of these people who go about taking numbers of engines and they print a book’, answered the concerned Detective Inspector. A fellow Inspector added that ‘No one knows who is running this thing. We have made enquiries but we have not traced them yet’ (Gateshead Post, 1949, 12). Although the insinuation of a criminal conspiracy comes across as pretty clueless, the police certainly took the issue seriously. Trainspotting was, at times, regarded as particularly concerning, even to the extent of being portrayed as a gateway into more serious criminal activities by some members of the railway police force (Chambers, 2022). The same year that Robinson was hauled in front of the magistrate, the government passed the British Transport Commission Act relating to the formation of the organisation and granting it various legal powers. Smuggled into Part VII section 55 of the Act there were also some laws pertaining to railway trespass that seemed to be a direct response to reports in the press (BTCA, 1949). Indeed, writing in the British Transport Commission Police Journal just a few years later, one member of the force specifically highlighted Section 55 with regards to juvenile trespass on the railways (Radcliffe, 1954).

V

Watching Luke Nicolson, the social-media personality professionally known as Francis Bourgeois, the viewer is aware that this is, to an extent, a performance. The viral trainspotter uses the contemporary image of the subculture to evoke a certain charm that hails back to an imagined past. The use of a fisheye GoPro in his social media videos, while he idiosyncratically wails with delight at passing locomotives, maintains a veneer of physical and social oddity. Yet, rather than the socially awkward, sexually frustrated, and obsessive bore the stereotype of the trainspotter would suppose him to be, his trainspotter appears alongside famous personalities and models exclusive fashion brands. Perhaps one aspect that allows him to avoid ridicule are the class associations he has curated for the character of Francis Bourgeois. The use of bourgeois in his character’s name immediately dissociates him from any vestiges of working-classness giving him space to be a loveable eccentric rather than a revolting nerd, as Acne might have had it. However, just like the mythical innocent past he invokes, the portrayal of the trainspotter has always been a social construction that has reflected wider social anxieties rather than the reality of trainspotting.

By the end of the twentieth century, in stark contrast to the folk devil of the immediate post-war period, the trainspotter had become a figure of fun in the popular imagination and a regular target of ridicule in media portrayals. By looking at the example of the contemporary comic Acne, I have shown how this stereotype was typically presented and repeated. In one episode of Acne’s strip the Train Spotters, its three protagonists are depicted trespassing on railway property in contradiction to their nerdy image. I argue this is a reference to trainspotting’s historical associations with deviancy. In the strip the steam engine functions as a visual device that takes the three characters out of the confines of the trainspotter-as-nerd and into the trainspotter-as-deviant of the past. Contradicting the established stereotype, the portrayal echoes a history of trespass that was a central facet of the trainspotting subculture as it formed in 1940s Britain.

From early on, the act of trespass became an important process in the performance of trainspotting. It functioned as a way to transgress the rules of the adult world and reclaim agency for children and youths who were themselves on the brink of adulthood. Trespass was also undertaken for emotional and functional reasons. As a thrill-seeking exercise trespassing on railway property was simply a way of confronting danger. Crossing a busy line was a potentially deadly risk, as was sneaking around engine sheds which were full of hazards. Such risks provided reward though allowing the intrepid spotter to collect numerous loco numbers in one site. Other forms of trespass such as placing a coin on the rails to be pressed by a passing train could be a daring way to fill the time between collecting numbers whilst in a stationary position. Trespass functioned as a way of pushing the ‘game’ of trainspotting to its limits, negotiating private space, and claiming ownership over it.

On the occurrence of trespassing Letherby and Reynolds ‘suggest that the social control of the rail enthusiast largely takes place within the group’, with full acceptance into the group earned as the unwritten rules are learned. (Letherby & Reynolds, 2005: 173). Clearly, this was not the case in post-war Britain where trainspotters were the target of campaigns by British Railways, alongside legal restrictions, and of course the policing of trainspotters’ behaviour by the railways police. Rather than being regulated from within the group, permissible behaviour was framed by institutions such as publishers, clubs, newspapers, and the railway authorities themselves. This attempt to reshape trainspotting was never fully realised and bunking continued to be a pillar of the trainspotting subculture. Thus the popular image we have today of the trainspotter projects something of an institutionally created myth that incorporates wider social and cultural anxieties around class, youth, and gender.

Thomas Chambers is an independent researcher and writer

from London. His interests revolve around contemporary

and historical graffiti as well as subcultural movements.

He has written about North American hobo culture, early graffiti cultures in Europe, and political graffiti during WWII. More recently he has researched the emergence of trainspotting as a youth subculture in post-war Britain.

- 1

Gayle Letherby and Gillian Reynolds have concluded that historically, trespass has not been treated as a serious problem with regards to trainspotting and the policing of it has been left to the trainspotters themselves. See Letherby, G. & Reynolds, G. (2005) Train Tracks: 172.

- 2

For a more ridiculous example of the supposed effect of ‘wokeness’ on railway heritage in the fevered imaginings of boomers check historian David Abulafia’s 2021 article ‘If the Woke Don’t Cancel Steam Trains, Then Green Extremists Will’ in The Telegraph.

- 3

Whittaker defines the term as ‘getting into railway depots by fair means or foul to take down loco numbers, keeping a low profile and avoiding railway staff’ (see Whittaker, 2015: 287). Alexander uses the term when describing trespassing into a shed at 4 am to reduce the risk of getting caught ( see Alexander, 2018: 149).

- 4

See Carter, 2014: 287, note 18 for uses of this term. After 1968, many trainspotters travelled abroad to chase down steam locomotives, one of whom, K. Taylorson, wrote A Gricer in Turkey in which he observed ‘that ‘gricing’ as a concept does not exist in Turkey, so even if you can explain what you are doing, you will not easily be able to explain why you are doing it!’ (Taylorson, 1975: 19).

- 5

A V2 being a class of steam locomotive.

- 6

Anyone familiar with modern graffiti magazines will no doubt recognise this practice. A particularly notorious example being that of the London-based Keep the Faith magazine, the editor of which, despite including a disclaimer that the publication did ‘not encourage any criminal act whatsoever, we accept no responsibility for the actions of our audience’ (Keep the Faith, 2010: 3), became the first publisher to be prosecuted for ‘encouraging the commission of criminal damage’ in the UK. See: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015ov/08/marcus-barnes-graffiti-art-can-be-a-positive-force-train-tagging.

- 7

The exception perhaps being Grant Dowie’s exuberant account which was originally written between 1968–70.

- 8

From the scrapbook of an unknown trainspotter in the author's collection.

Acne (1991) No. 1.

Acne (1991) No. 2.

Acne (1991) No. 4.

Acne (1991) No. 5.

Acne (January, 1992) No. 6.

Acne (1992) No. 8.

Acne (March, 1992) No. 10.

Acne (August, 1992) No. 18.

Alexander, J. N. (2018) Locolog Chronicles 1957–1968. Great Britain: Self published.

Allan, I. (1992) Driven By Steam. Coombelands:

Ian Allan Publishing.

Barnes, M. (2015) ‘Marcus Barnes: ‘Graffiti art can

be a positive force’”. The Guardian, November 8, 2015. [Online] Accessed May 23, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015ov/08/marcus-barnes-graffiti-art-can-be-a-positive-force-train-tagging.

Boston Guardian (1957) ‘Train Spotters Banned at Grantham’. August 14, 1957: 6.

Bradley, S. (2016) The Railways: Nation, Network and People. St Ives: Profile Books.

British Railways Steam Locomotive Class 2F-O 58891

at Abercynon Shed in 1955. (26/06/1955) Neville Stead Collection.

British Transport Commission Act, 1949. Catalogue ref:

HL/PO/JO/10/101531.

File No. 01704.

Carter, I. (2014) British Railway Enthusiasm. Manchester University Press.

Chambers, T. (2022) The Invention of Trainspotting: Images of Steam, 1942–68. Unpublished dissertation: Goldsmiths, UoL.

Channel 4 (2022) ‘Francis's Sexy Audition For Love Island | Trainspotting With Francis Bourgeois’. YouTube [Online]. Accessed February 26, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_wRqHk49d5A.

Dowie, G. (2011) A Hard Day’s Week Railrover Trainspotting On the London Midland Region August 1965. Peterborough: Fast Print Publishing.

Gateshead Post (1949) ‘Police Want to Know About Numbers Firm’. January 28, 1949: 12.

Grimsley, R. S. (1947) The British Locomotive Shed Directory. Birmingham: Gilbert Whitehouse.

Halifax Daily Courier and Guardian (1954) ‘“Train Spotters” Behaviour Has Improved’. November 11, 1954:6.

Harvey, M. (2017) Forget the Anorak: What Trainspotting Was Really Like. Cheltenham: The History Press.

Keep the Faith (2010) No. 1.

Leicester Chronicle (1950) ‘Taking Their Names and Numbers’. September 16,

1950: 10.

Leicester Evening Mail (1955) ‘Train Spotters ‘on the Spot’’. September 26, 1955: 1.

Letherby, G. & Reynolds, G. (2005) Train Tracks: Work, Play and Politics on the Railways. King’s Lynn: Berg.

Liverpool Echo and Evening Express (1960) ‘“Missile Alley” Families Respond to Safety Plea’. July 15, 1960: 7.

Macdonald, N. (2002) The Graffiti Subculture: Youth, Masculinity and Identity in London and New York. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mathison, P. (2006) Shed Bashing With the Beatles: A Trainspotter in the Swinging Sixties. Newport: Dead Good Publications.

Midland Counties Tribune (1949) ‘Railway Trespass’. September 23, 1949: 4.

Radcliffe, F. (1954) ‘The Serious Side of Juvenile Trespass’. British Transport Commission Police Journal, 2(11): 13. From the British Transport Police Journals, 1948–1990 digitised collection.

‘Spotters' Code’ Poster. 1998-10828-1953.

Tamworth Herald (1944) ‘Borough Juvenile Court: “Stupid and Dangerous”’. November 25, 1944: 3.

Taylorson, K. (1975) A Gricer in Turkey. Barbican: Self Published.

The Grantham Journal (1961) “Just Taking Numbers” But He Was Also Trespassing’. September 22, 1961: 16.

Warrington, S. (2016) ‘Jubilees’ and Jubblys’:

A Trainspotter’s Story 1959–64 Part I. Great Addington: Silver Link Publishing.

Whittaker, N. (2016) Platform Souls: The Trainspotter as 20th-Century Hero. St Ives: Icon Books.

Wolmar, C. (2008) Fire & Steam: How the Railways Transformed Britain. London: Atlantic Books.