Introduction

Although street art and style writing graffiti in the early 1980s was much less often documented than in 2020, illegal street works by big names such as Keith Haring (1958–90), Richard Hambleton (1952–2017), or Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–88) were photographed and published quite frequently in mass media already in the '80s, even though this concerned only a fraction of their work.

Like Hambleton, Haring rarely documented his own street works. Both had photographers who photographed their works anyway – people who had gotten their permission to take pictures and who they supplied with information before or after creating an artwork. As opposed to the case of Hambleton, hardly any of Haring's illegal works were photographed more than once. This is because of the ephemerality of his preferred medium in the New York underground system: chalk, which is nowhere near as durable and wall-invasive as the tar black paint Hambleton used to work with. But Haring, like graffiti writers, also quite frequently used marker pens, whose marks were supposed to stay around for much longer.

However ubiquitous his works were, they were hardly documented at the time. The unsanctioned works on the streets (not in the underground) I discuss in this article have to be looked at as some of the rare documented examples of many lost figurative tags by Haring in Manhattan before 1985. The present analysis deals mostly with Haring‘s illegal interactions with others (including Basquiat and Hambleton) on the streets of New York City. Instead of talking about his well-documented murals or official interactions and diverse collaborations, I analyse photos of a few urban walls, for which the term ‘collaboration’ is less fitting than ‘shared walls’.

Haring's main source of influence when he started his signature street art drawings after some experiments with xerox art and stencil art (Deitch et al, 2008: 39, 52–59), was the two years younger Basquiat aka SAMO, who was probably also the first one with whom Haring deliberately shared walls:

[T]here were a lot of things in New York that influenced me: graffiti writers, and street artists. People like Jenny Holzer, who took propaganda-like texts onto the streets, which aroused the public curiosity. SAMO, who used the whole of downtown Manhattan as his field of operation, was the first to write a sort of literary graffiti. He added a kind of message to his name which conveyed an impression of poetry: statements criticizing culture, society and people themselves. Since they were so much more than ordinary graffiti, they opened up new vistas to me.

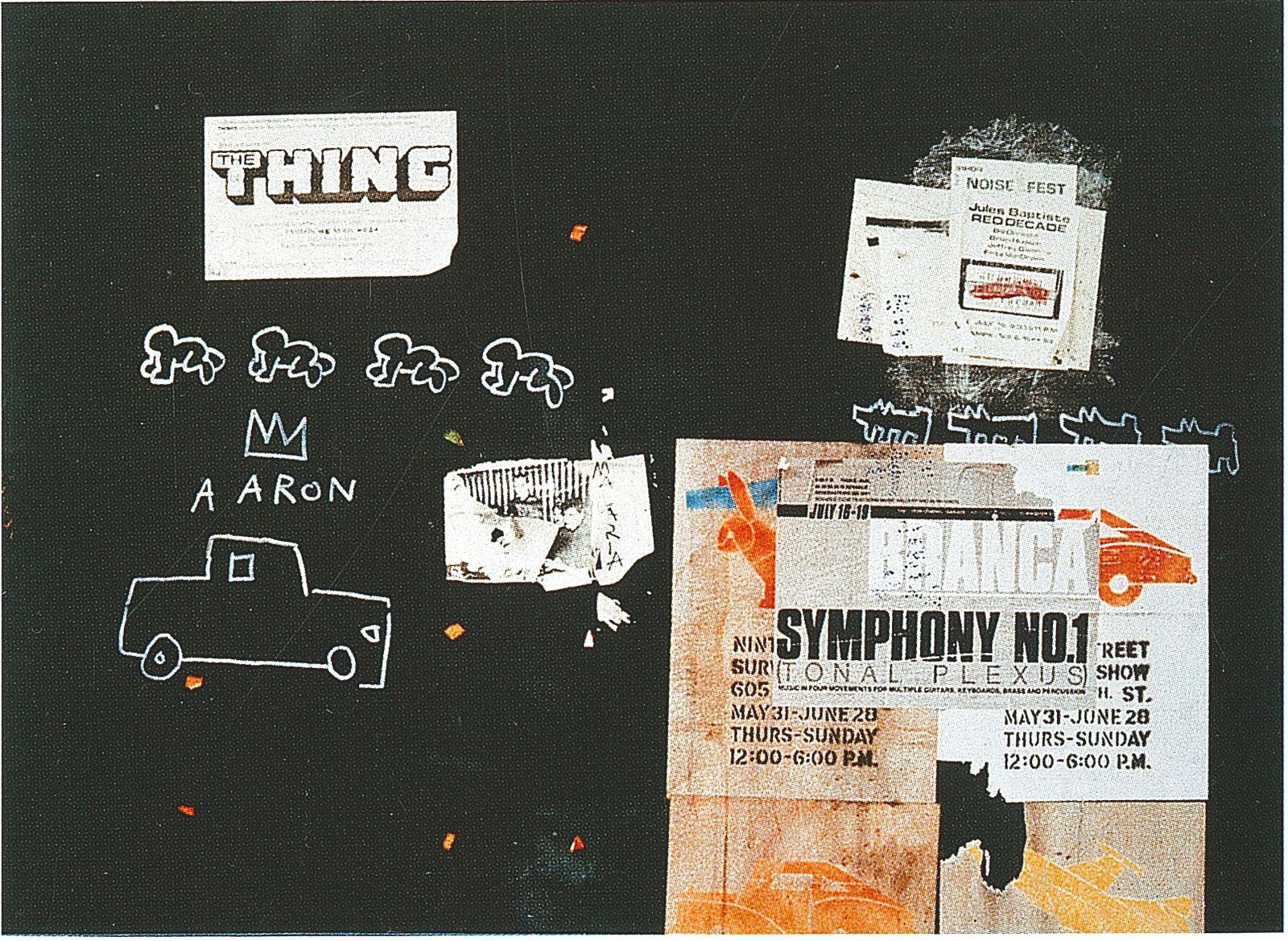

I know of only two urban surfaces on which Basquiat and Haring left traces together and that have been photographically documented. The better-known representation of the two concerns a seemingly temporary plywood wall, which is even preserved in two different ways: as an earlier photo and as a later plywood street fragment. Both show Haring's crawling figure, often called a baby, and his animal, often referred to as a dog, as well as Basquiat's crown above the word ‘Aaron’ and a crude, angular drawing of a car. With name signatures lacking, both these artists' signs act as pictorial signatures, since they appear in a variety of their other works as well. Apparently, both artists worked with the same tool, i.e. white chalk of the same thickness, which may also indicate that both were drawing on the wall at the same time. It is obviously not a real collaboration, rather two pictorial signatures side by side, since apart from the (possibly) shared work equipment and the shared wall, no obvious interaction between the two iconic images is discernible. This is not unusual for graffiti writers, who often work at the same time, that is to say, side by side rather than really together.

Most representations of this shared wall are incomplete. The best available representation of this shared wall was photographed by Klaus Wittmann (Figure 1) as the construction fence stealer cut off Basquiat's car. This shared wall is dated to 1981 (Deitch et al., 2008: 101). Reasons for that might be that Basquiat was no longer active under the name SAMO, which he was until early 1980 (Goldstein, 2017) and already when Haring met him around 1979 (Gruen, 1991: 52–53). Since Haring did not begin to draw his crawling (baby) figure until late 1980, and as it still had no rays, which he started to add even later (ibid.: 62, 68), 1981 seems to be right. Photos of the same two (and most well-known) Haring figures on toilet walls of the club Peppermint Lounge, which date from 1981, provide further evidence, as they equally show the crawling figure without radiation beams (Deitch et al., 2008: 101). The same applies for an exhibition invitation card from February 1981 (ibid.: 160). The rear poster layer on the plywood was pasted over Haring's ‘dogs’. It got stencil designs by Anton Van Dalen on it, advertising an exhibition that ended on Sunday June 20, which was a Sunday in 1981, but not in 1982. Since the exhibition started in May, Haring's chalk drawing might have already been on that plywood at that time. After 1981, Haring and Basquiat became alienated because, according to Haring, they were forced into a competitive situation against each other (Gruen 1991; 54). This makes a joint spraying action after 1981 less likely as they probably would not combine or attach their motifs on one surface, after one might have seen the work of the other on a wall. Wittmann's photo is probably from July 1981, the date of the most recent poster depicted on it (‘Symphony No. 1’). The plywood piece was of course produced quite some time later as it has some additional style writing graffiti on it, as well as other posters. Both motifs are not primarily relevant as individual works of art, but as with graffiti tags, they gain significance with quantity. Haring and Basquiat were known for leaving their drawings everywhere on the streets of Manhattan. Their drawings were, and aimed to be, recognisable in style and visual content.

Haring produced early crawling figures, animals (the ‘dog’) and smiling faces drawn with black markers elsewhere in New York City too, and also with chalk on the ground in a park (illustrated in Deitch et al., 2008: 98–101). He maintained this semi-legal, harmless and ephemeral activity for years, also exporting it overseas. During his stay in Cologne, Germany, in 1984, for example, he drew in chalk in front of the cathedral and on the doors of the gallery that featured his works (Maenz, 1984), but also in the studio of the young and wild local painter Walter Dahn (van Treeck, 2001: 152).

Haring's chalk and marker drawings on the streets of the New York City were rarely documented, much in contrast to his chalk drawings in the New York subway system, for which he published even his own book. The fact that his drawings were omnipresent at that time is highlighted in a quote by well-known graffiti writer Andrew Witten aka Zephyr (Witten, 2011: I):

I spotted my first baby on Canal Street. It was 1979 […]. The Mudd Club […] was the epicenter of the neo-punk no wave scene. Because it was located on White Street, a block south of Pearl Paint, Canal Street was common territory for punk band pestering and occasional one-off acts of avant-garde street decoration. But these babies were different. The babies, quickly hand-rendered yet remarkably exact, were drawn onto the concrete edge around the exit of the subway station. They were sweet and fresh, and Futura and I immediately knew we were looking at something special. The babies were rendered with our tool, a black Niji marker. In 1979, the black Niji magic marker was the staple for all self-respecting vandals. And had the babies not been so damn cute, they could have easily made us mad. Graffiti writers are, if nothing else, territorial, pathologically possessive, and bombastic. We consider even our magic markers sacred. We don't want you using them. The babies multiplied like Chinese wisteria. Within weeks they were everywhere, and then it was all about ‘Who?’ The ‘Who’ we soon discovered, it was a low-talking, mousy kid from Pennsylvania Dutch Country named Keith.

Although Zephyr's dating is two years too early, it points to the recognition of Haring's illegal work by graffiti writers and to the fact that in addition to their graffiti writing tag quality (although he himself created a figurative tag), Haring also took up their working tool (the Niji marker) and their aim for quantity during a longer period of time – which did not apply to the temporary punk Xerox posters and stencils with which Haring had also experimented months earlier (Deitch et al, 2008: 39, 52–59). Haring also conducted his self-authorised institutionalisation, parallel to his self-authorised drawings on the street: he curated large one-night group exhibitions in clubs, for instance Club 57 and the aforementioned Mudd Club (Gruen 1991; 62). The first of these Haring-curated pop-up club exhibitions took place on September 15, 1980 (Haring, 1980), a month before he started drawing on the street. The second one, in February 1981 (Haring, 1981), featured a total of 80 artists, including Basquiat and Zephyr, as well as several graffiti writers who were already well-known, such as Lee (Quiñones), (Donald) Dondi (White), (Stephen) Rammellzee (Piccirello), Fab5 Freddie (Frederick Brathwaite) and (John) Crash (Matos), all of whom are among the most influential in US style writing graffiti history.

David Wojnarowicz – who worked with Haring at the club called Danceteria (Carr 2012: 159) and died of AIDS in 1992, two years after Haring – was also represented in both exhibitions. Brazilian photographer Fernando Natalici documented a door in the East Village (Figure 1) which had – in addition to written tags by graffiti writers – image tags by Haring, Basquiat, and Wojnarowicz on it. Again, it is possible that here Basquiat and Haring worked together with markers, since their stroke width is similar and their works – Haring's (already radiant) baby and Basquiat's crown with the word ‘coal’, combined with Hitler's face, a cubist skull and an Indian tent – were created at the same height. Wojnarowicz's stenciled burning house signature tag seems to have been added later next to Basquiat's part, as in terms of placement it rather filled the last gap on the upper left half of the door. According to Wojnarowicz‘s former collaborator Julie Hair, Wojnarowicz also created fake ‘mutant’ Haring chalk drawings in public space (Blanché, 2020), none of which have been documented, unfortunately. At the time such works formed a different kind of interaction among street artists that oscillated between mockery and the graffiti writer's toy concept of mimicking the style of others.

Much in the way that Haring and Basquiat used their figurative tags, Wojnarowicz also used his stencils in a modular way, i.e. the range of pictorial elements he applied could mean different things in different combinations. Haring cites Beat Generation writer William Burroughs‘ (1914–97) cut-up technique as an inspiration to work in that modular way (Deitch et al., 2008: 96). On the door in Figure 1 there is also the figurative tag of the Brazilian street art pioneer Alex Vallauri (1949–87), who began using a similar modular cut-up technique with stencils in São Paulo (Dettmann Wandekoken, 2017: 69–70; MIS, 2017: 14–15; Rota-Rossi, 2013: 107) even before Basquiat, Haring, or Wojnarowicz did so in New York. Vallauri demonstrated this concept also on many New York walls (illustrated in MIS, 2017: 18–23). His modular approach also integrated the works of other artists: best documented are his many shared walls with Richard Hambleton, although none of the photographers seemed to have known Vallauri's name. Vallauri appreciated Haring's work, as he mentioned in a letter (Rota-Rossi, 2013: 169–170). He got to know Basquiat personally and told his biographer João Spinelli about a joint spraying action with Basquiat (Dettmann Wandekoken, 2017: 37) – perhaps on this very door? Since Vallauri was not in New York City before 1982 (Dettmann Wandekoken, 2017: 84), the early dating of the photo (1979–80) by the gallery that sells it in 2020 (1stdibs, 2020) is unrealistic.

Haring's ‘baby’ tag on that door was crossed out, with the derogatory expression ‘YIPE!’ written above it with the same thick marker pen. Haring did not only make friends with the omnipresence of his tag. Maybe it was even Basquiat who crossed out Haring's baby as Basquiat had done (still as SAMO) on several occasions to the stenciled figure of a man with an umbrella by Eric Drooker in 1979, documented in a few photos by Henry Flynt. When confronted by Drooker, Basquiat stated (Drooker, 2018): ‘I cross out words so you will see them more: the fact that they are obscured makes you want to read them.’

Haring himself seemed never to have crossed out the tags of others, the most violent way of interaction, but his approach was still ambivalent.In 1989 he stated (Deitch et al., 2008: 96):

From the beginning, I would fit my tags in between other ones and never did them on top of anyone else's. They were always in between because I didn't want to have fights with anyone else. I wanted to fit in with other people's stuff. I would do them on the bottom of a lamppost, if I saw an empty spot where there was some graffiti.

The opposite of what he stated can be seen in a photo next to a reprint of this quotation: Haring is standing in front of large versions of his chalk figures, which he had drawn in all-over manner over style writing graffiti tags behind it (illustrated in Deitch et al., 2008: 97). In the subway system, he did actually often place his chalk drawings in spaces next to graffiti that was already there (illustrated in Haring, 1984: unpaged). Apparently, conversations or other experiences with graffiti writers had triggered a process of cognition within him, but this was not yet completed in mid-1981, when this photo was probably taken – if one assumes that the Symphony No. 1 poster in the background from July 16–19, 1981 did not hang there a long time.

Painting on Hambleton‘s Shadowmen

Although the concept of street art repeat photography (Andron, 2016) or longitudinal photo-documentation of urban art (Hansen & Flynn, 2015) had not yet been invented in the 80s, there were already street works, like the ones by Hambleton, that were photographed repeatedly by different photographers, such as Franc Palaia (1982), Thomas Christ (1987), and Hank O’Neal (2014). They did so independently of each other and for two reasons: the works were often left in place (albeit not untouched) for years due to a lack of money of building owners and local authorities, and because their author, Hambleton, was quite famous at that time.

This important street art pioneer and classically trained artist had started creating street art years before Haring and Basquiat, in the mid-1970s (Rappolt, 2010). Hambleton was present in mainstream media as prominently as Haring and Basquiat (ibid.), and initially his art was worth as much as Haring's and more than Basquiat's (Gracia, 1983). Both Basquiat and Haring at least once painted on a (different) shadowman by Hambleton. Shadowman paintings were omnipresent in Manhattan in the early 1980s: they were a series of silhouetted images of some mysterious person that Hambleton began in November 1980 and called ‘Nightlife’ (Smith, 1982). After a number of years – at the height of his popularity – he started to produce a different type of art that few were interested in, while at the same time getting seriously addicted to drugs. Consequently, he virtually vanished from the scene. Although he did survive both Basquiat and Haring by more than 25 years, produc-ing commissioned artworks for wealthy buyers until his death in 2017, he lived the final decades of his life in poverty and misery.

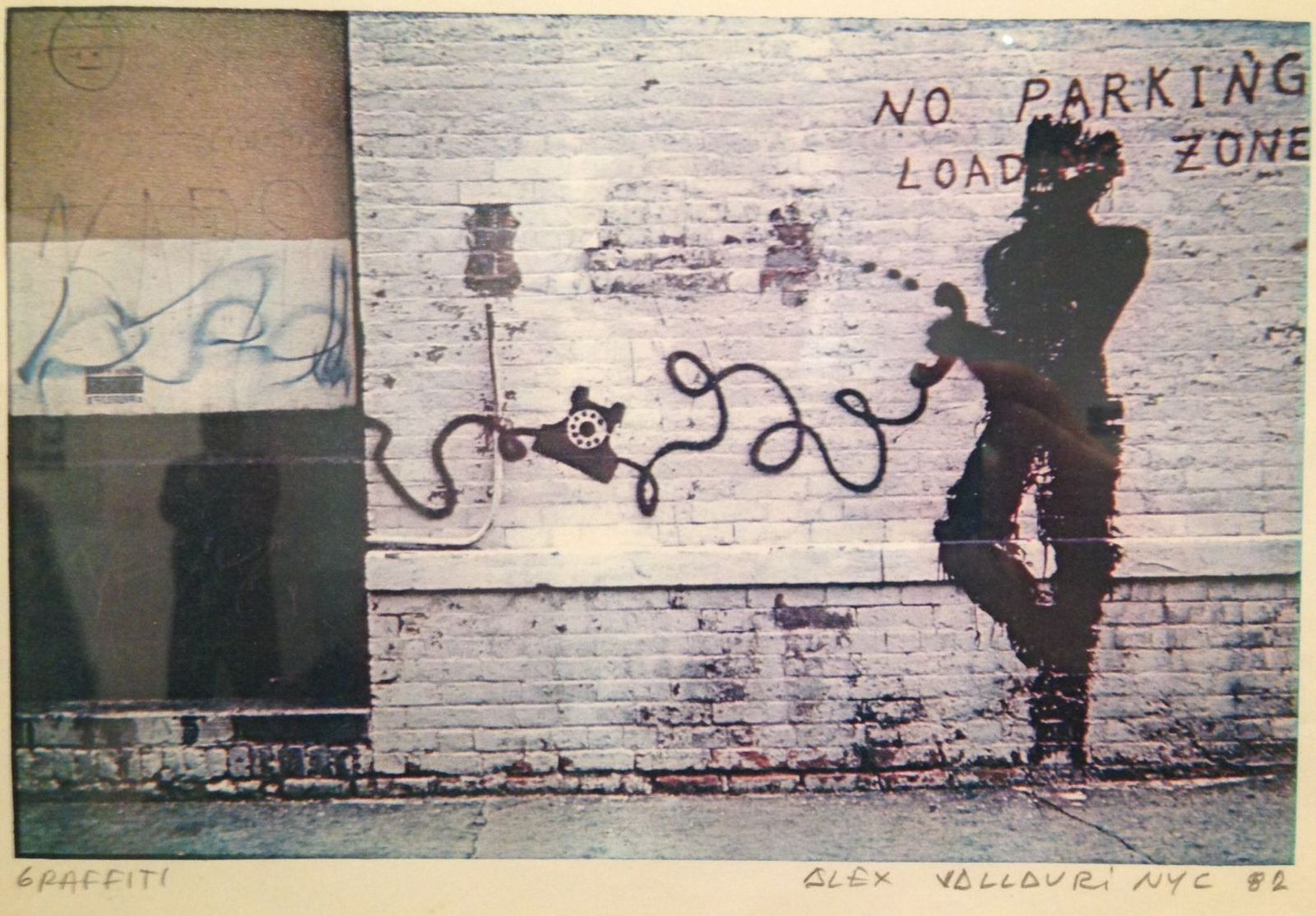

Although Hambleton's eerie Shadowmen characters invited interaction – life-sized and completely black as they were – the artist himself did not always appreciate the interventions of his colleagues. In 1982, his regular photographer in New York (Ortiz, 2017), Franc Palaia, published a photo of one shadowman (Palaia, 1982) where someone – presumably Hambleton himself – had carefully removed an addition by Alex Vallauri: a stenciled telephone with a cable attached to it. This careful removal of the Vallauri part rather precludes the possibility that a homeowner was responsible for it. A photo by Vallauri (Figure 2), on the other hand, shows both works without the buff (Dettmann Wandekoken, 2017: 122). Interactions and additions by others softened the uncanny nature of these shadow figures, or ridiculed them to some extent. This cannot be said of Basquiat's addition of a gloomy skull, which was photographed by O'Neal, but it did apply to Vallauri's stenciled phone and Harings' radiant baby drawing, which he put inside the head of a shadowman, as photographed for instance by Thomas Christ (1987: unpaged). A sinister man who got a baby inside his head appears less sinister. The shadowman (without Haring's addition) was illustrated in the 1982 Palaia book authorised by Hambleton. By adding his baby, Haring had blacked out the shadowman's eyes that were still visible in that earlier photo by Palaia. As for Basquiat's addition to Hambleton's shadowman – a limited edition photo of which by Palaia is today on sale for £10,000 – later photos by O‘Neal seem to be proof that Hambleton himself had apparently painted over that one as well. He seemed to have liked interactions more as a backdrop for his work, not front stage. However, decades later Hambleton seemed to feel differently. When confronted with Basquiat's skull over his shadowmen, he said he ‘loved the interaction’ (Jacoby, 2017, TC: 23.54 min.).

Because Haring, Hambleton, and Basquiat were all well-known in early 1980s New York City, I would not argue that one of them acted as a ‘free rider’ in relation to the other with these kinds of interactions. I would insinuate this only – to a certain extent – to Wojnarowicz, who admired Haring‘s and Basquiat's street work (Carr, 2012: 165, 175–176), and tried to get into the art world in 1982. On one occasion, Wojnarowicz stenciled his burning house tag also next to a Hambleton's shadowman (illustrated in Palaia, 2011: 30).

Vallauri's interactions with Hambleton are actually the most interesting: from a non-Brazilian point of view it seems that with his quite frequent additions to Hambleton's shadowmen (they never happened the other way around) he made use of one of the best known artists in New York. Vallauri admired Hambleton's work, as he himself stated (Dettmann Wandekoken, 2017: 37), though he never seemed to have cashed in on his interactions with the shadowmen. As a result, Hambleton is remarkably absent from the extensive Brazilian literature on Vallauri. Vallauri, very famous in his home country, was either called the Brazilian Warhol or the Brazilian Haring. He did sell and spread photos of his New York street works, including his interactions with Hambleton, but without crediting him for it. Consequently, examples of those shared walls, reproduced for instance in a dissertation by Dettmann Wandekoken (2017: 122), or to be admired in a collection of Vallauri photos in the possession of the Museum of Sound and Image in São Paulo (2017: 48), simply fail to mention Hambleton. In this collection, Hambleton's part of the artwork is even cut out almost completely. Ironically, it concerns the same shadowman painting in which allegedly Hambleton himself removed Vallauri's part. So Hambleton did not like the interactions of Vallauri, who did not really take a free ride on his fame, but never gave him any credits either.

Several of the sanctioned murals by Haring were also interactions with artworks that had been painted there before. On the Berlin Wall, Haring created his drawings over a row of large Statue of Liberty stencils by French artist Thierry Noir (2018):

On October 23, 1986, three months after I had painted the Statues of Liberty, I heard […] that Keith Haring was in Berlin to paint the Wall at Checkpoint Charlie. I went there and I saw that my statues were all gone, painted over by a huge amount of yellow paint. I talked with Keith about this and he was embarrassed and apologised to me. He said that: ‘in New York you can get killed for that‘. [T]he section of Wall had been preprepared for him with a yellow base that went over the Statues that I had painted. The yellow colour was very transparent so it was possible to see my Statues through it.

So Haring was well aware of the physical consequences of painting over the works of others, which he did not do out of decency. In a short-lived variation of his famous Crack is Wack Mural, this time at 525 East Houston Street in New York City, Haring apparently did paint over tags from graffiti writers. In order to show them his respect, and probably also to prevent them from destroying his mural out of revenge, he integrated the following inscription: ‘KH86 LES – NYC CBS – MMC RESPECT’. KH86 takes up the New York graffiti writer habit of having a pseudonym that consists of letters followed by numbers, which is often an abbreviation of the number of the street the writer is from, such as the well-known Taki183. In this case, ‘KH86’ stands for Haring's initials and the year in which he produced that mural, similar to the way you would see it in a classic painting. ‘LES – NYC’ and ‘CBS – MMC’ in the inscription are two writers, or rather, two crews to whom Haring paid his ‘RESPECT’.

Conclusion

Haring, Basquiat, Wojnarowicz, and Vallauri all used their figurative signature tags both in an additive as well as a modular way – modular not only as far as their own imagery was concerned, but also that of others such as Hambleton, as works by various artists popped up on the same urban walls. Those figurative, Burroughs‘ cut-up-like tags did not only cement each artist's fame as a result of widespread distribution, similar to graffiti writer tags, they thus also led to numerous different compositions and local situations that included the works of several different artists. Haring put his tag simply next to those of others, for instance Basquiat's, and he built new visual connections with the work of Hambleton, as did Vallauri and Basquiat. Haring, Basquiat, and Vallauri painting over or adding elements to a number of Hambleton's shadowmen can be seen as a real interaction in terms of content, but could also be interpreted as a form of ridicule. One Hambleton body was fitted with a Basquiat skull while another one got a Haring child for a brain. For his part, Vallauri made Hambleton's shadowmen more communicative and lighter, he never destroyed them. Those interactions on shared walls rarely seemed to be an act of taking a free ride, rather, they were artistic expressions on par with each other. Nevertheless, such interactions were not always desired by the one whose work appeared first on a wall, as Hambleton sometimes removed the interventions of others.

At least occasionally Haring deliberately painted over other street artists, the most aggressive form of interaction with others, although he stated he always did the opposite. If he did, Haring sometimes apologised or paid respect to those whose works he had painted over. At times, his own works also got painted over, although he soon tried to fill in his drawings rather than actually interact with others, as for instance Vallauri did with Hambleton.

- 1

Tseng Kwong Chi documented many of Haring's chalk drawings in his book: Art in Transit: Subway Drawings, New York, 1985. Franc Palaia photographed Hambleton's Shadowmen in New York City, self-published by Palaia as: Nightlife. Paintings by Richard Hambleton, 1982–83. Handmade books, New York, 1982.

- 2

Haring quoted in the edited transcript of the National Gallery of Victoria Multimedia Guide for the exhibition ‘Keith Haring | Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines‘. Melbourne, 2019

- 3

In 1989 Haring described the ‘baby’ and the ‘dog’ as interpretations by others (Deitch et al, 2008: 96).

- 4

See for instance Palaia (1982), Frank & McKenzie (1987: 51) Christ (1987).

- 5

At least four times SAMO (Jean-Michel Basquiat and Al Diaz) interacted with this umbrella man stencil by Eric Drooker around 1979, documented in photos by Henry Flynt. Usually Drooker was crossed out: http://www.henryflynt.org/overviews/artwork_images/samo/5.jpg; http://www.henryflynt.org/overviews/artwork_images/samo/7.jpg; http://www.henryflynt.org/overviews/artwork_images/samo/15.jpg; http://www.henryflynt.org/overviews/artwork_images/samo/36.jpg.

- 6

In 2017, Marc Miller from 98 Bowery Gallery, New York, sold a copy of the first edition of Palaia's book from 1982. On the gallery website Miller archived some scans from the book, among them is also the photo in question. Accessed July 17, 2020. http://gallery.98bowery.com/wp-content/uploads/nightlife-page.jpg Hank O'Neal also took a photo of this particular Hambleton shadowman. His photo depicts Vallauri's part completely painted over, including the telephone, which is cut off in Palaia's photo. Accessed July 17, 2020. http://www.hankonealphoto.com/images/shadowman_images/Image_45,_Lower_East_Side,%20New%20York%20City,_1982.jpg

- 7

Hank O'Neal, Richard Hambleton, and Jean-Michel Basquiat Skull 1981–82, c-print [2015] on aluminium dibond mount, 104.1 x 86.36 cm, edition of 50, reproduced on O'Neal's website. Accessed July 17, 2020. http://www.hankonealphoto.com/images/shadowman_images/Image_37,_Lower_East_Side,%20New%20York%20City,_1982.jpg

- 8

The Woodward Gallery posted a different photo of the same shared Hambleton-Haring wall on their Instagram account in 2018, without naming the photographer. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/p/Bg9qoA5hfsk/

- 9

The Woodward Gallery apparently sold the Hank O'Neal photo ‘Richard Hambleton and Jean-Michel Basquiat Skull‘ for £10,000. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://www.urbanartspace.co.uk/product/richard-hambleton-and-jean-michel-basquiat-skull/

- 10

Hank O'Neal's photos depict more graffiti around the shadowman, but not the Basquiat skull anymore, which was painted over by then. Accessed July 17, 2020. http://www.hankonealphoto.com/images/shadowman_images/Image_14,_Lower_East_Side,%20New%20York%20City,_1982.jpg and http://www.hankonealphoto.com/images/shadowman_images/Image_15,_Lower_East_Side,%20New%20York%20City,_1982.jpg

- 11

I know of at least nine Vallauri interactions with different Hambleton shadowmen, documented by different photographers. I deal with them in more detail in my upcoming publication on the street art history of stencils.

- 12

See Hank O'Neal‘s photo. Accessed July 17, 2020. http://www.hankonealphoto.com/images/shadowman_images/Image_45,_Lower_East_Side,%20New%20York%20City,_1982.jpg

- 13

Keith Haring, Crack is Wack! [alternative version], documented by photographer Matt Weber, 1986. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://weber-street-photography.com/2012/06/25/crack-is-wack-keith-haring-1986/

1stdibs (2020) Fernando Natalici, Rare Basquiat, Keith Haring Street Art Photo c.1979. [Online] Accessed July 17, 2020. https://www.1stdibs.com/art/photography/black-white-

photography/fernando-natalici-

rare-basquiat-keith-haring-street-art-photo-c1979/id-a_4927531/

Andron, S. (2016) ‘Paint. Buff. Shoot. Repeat. Re-photographing Graffiti in London’, in Campkin, B. & Duijzings, G. (Eds), Engaged Urbanism. Cities and Methodologies.

London: IB Tauris.

Blanché, U. (2020)

Unpublished email interview with Julie Hair, May 20, 2020.

Carr, C. (2012) Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz. New York: Bloomsbury.

Christ, T. (1987) Urban Graffiti: New York 82/83. Basel: Aragon.

Deitch, J. et al. (2008) Keith Haring. New York: Rizzoli.

Dettmann Wandekoken, K. (2017) Alex Vallauri: graffiti

e a cidade dos afetos. Dissertation, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo Vitória. [Online] Accessed February 19, 2021. http://repositorio.ufes.br/bitstream/10/8489/1/tese_10593_DISSERTA%c3%87%c3%83O%20MESTRADO%20KATLER%20FINAL%20REVISADO.pdf.

Drooker, E. (2018)

‘My very first street art’. (Facebook post, December 15, 2018). [Online] Accessed 19 February, 2021. https://www.facebook.com/eric.drooker/posts/10156982085653336.

Goldstein, C. (2017)

‘Basquiat, the Teenage Years? His Onetime Collaborator Releases a Trove of Unpublished Photos and Prints’. Artnet. [Online] Accessed July 17, 2020. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/basquiat-samo-al-

diaz-977438.

Gracia, E. (1983) ‘New York. The Greening of Graffiti’. International Herald Tribune, January 8 & 9, 1983.

Frank, P. & McKenzie, M. (1987) New, Used and Improved. Art for the 80's. New York: Abbeville Press.

Hansen, S. & Flynn, D. (2015) ‘Longitudinal photo-

documentation: Recording living walls’. SAUC Journal, 1(1): 26–31.

Haring, K. (1980) Club 57 presents: Xerox. September 15, 1980. David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library. Journals, 1980–81: Aug, Paris/NY. [Online], Accessed July 17, 2020. http://sites.dlib.nyu.edu/viewer/photos/woj_mss092_ref26/5?embed=true.

Haring, K. (1981)

‘Lower Manhattan Drawing Show,’

Press Release Flyer,

February 10, 1981.

Haring, K. (1984) Art in Transit: Subway Drawings by Keith Haring. New York: Harmony Books.

Jacoby, O. (2017) Shadowman.

A Film by Oren Jacoby. 81 min.

Maenz, P. (1984) Keith Haring at Paul Maenz. Cologne: Paul Maenz.

MIS (2017) Alex Vallauri – Foto. São Paulo: Museu

da Imagem e do Som [MIS].

Noir, T. (2018) ‘Making friends with Keith Haring’. [Online] Accessed July 17, 2020. https://thierrynoir.com/berlin-wall/.

O'Neal, H. (2014) ‘The Shadow Man’. [Online] Accessed July 17, 2020. https://www.hankoneal.com/index.php/the-shadow-man.

Ortiz, J. (2017) ‘The Local Photographer Who Captured Richard Hambleton's ‘Shadowman’. Hudson Valley Magazine. [Online] Accessed July 17, 2020. https://hvmag.com/life-style/the-local-photographer-who-captured-richard-hambletons-shadowman/.

Palaia, F. (1982) Nightlife, Xerox book., New York: Handmade Books. (Reissued and expanded in colour in 2011.)

Rappolt, M. (2010) ‘Richard Hambleton New York’. London: Art Review Publications.

Rota-Rossi, B. (2013)

Alex Vallauri. Da Gravura Ao Grafite. São Paulo: Olhares.

Smith, H. (1982) ‘Chasing Shadows’. The Village Voice, July 6, 1982.

Van Treeck, B. (2001) Graffiti Lexikon. Berlin: Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf.

Witten, A. (2011) Foreword in Edlin, J. (Ed.) Graffiti 365. New York: Abrams.