It is common practice to focus on the artist or cultural agent’s role in gentrification – to examine their position as either complicit enabler or socio-aesthetic activist in urban art initiatives (Courage, 2017; Deutsche, 1996; Deutsche and Ryan, 1984; Graham, 2017; Miles, 1997; Pritchard, 2019a, 2019b; Rosler, 1991). However, as urban art scholarship continues to devote its attention to the role of the art professional in gentrification, it arguably prolongs the out-of-date idea of the exalted, over-mythologised artist. Furthermore, a vital theoretical omission arises – precarious working-class communities, who are at the centre of urban gentrification urgencies, are addressed as secondary actors. If urban-centric art debates are to live up to their radical and progressive reputations, would it not make more sense to focus on the precarious working-class communities who are facing dispossession and displacement? This paper aims to shift focus away from the artist and cultural producer, examining instead the importance of working-class communities in European anti-gentrification art projects within the last 30 years. The terms and conditions of these projects are that they are working-class initiated/driven, are durational, and operate on a 1:1 scale. It is not the intention of this paper to completely disregard the artist’s presence in anti-gentrification art projects, but rather, to consider them as supportive facilitators (as opposed to exalted heroes or protagonists) of gentrification resistance. With the urban working class at the centre of its analysis, this paper will highlight the various tactics and socio-aesthetic tools, which have enabled these communities to hold their immediate needs and struggles at the heart of the production process. Focusing on the working class in anti-gentrification art projects is not only a corrective to the multitude of artist-centred analyses, but is also a requirement in highlighting this field’s apparent ‘working-class turn’. In the mid-‘90s, urban working-class communities revealed a determination to be active agents of creative gentrification resistance and no longer passive receivers of art’s gentrifying, colonising arm. working-class communities at this time gained authorial rights in anti-gentrification art initiatives, as they, more generally, sought freedom from outsourced political power.

Neoliberalism and the Failures of Representative Politics

The examples of anti-gentrification art projects addressed in this paper either occurred or commenced in the ‘90s – a decade marked by the triumph of neoliberal capitalism in the West and its extension into urban policy. In the UK, the introduction of ‘New Labour’ promised a ‘third way’ between socialism and capitalism. However, in reality, the neoliberal strand of New Labour was dominant and its social-democratic strand, subordinate. As Duncan and Schimpfössl (2019) assert, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, discredited the idea of socialism, and were perceived as signalling the definitive victory of capitalism (Duncan and Schimpfössl, 2019: 3). This era’s neoliberal politics and social welfare decline also possessed urban modalities. At the dawn of the ‘90s, the rapidly intensifying neoliberal economy stimulated a shift towards a new form of urban governance. This new model of urban governance, which Harvey described as ‘urban entrepreneurialism’, prioritised ‘investment and economic development with the speculative construction of place rather than amelioration of conditions within a particular territory as its immediate (though by no means exclusive) political and economic goal’ (Harvey, 1989: 8). This prioritisation of western cities as centres of financial capitalism ostensibly worsened gentrification levels.

The ‘90s was also a period in which more structured forms of political representation, such as trade unions, were on the decline (Wald, 1998: 70). This decline of consensus and representative democracy, which reached an apex of sorts in the ‘90s, seemingly figured into the decade’s demonstrable increase in anti-gentrification art being initiated and driven by the urban working class. The failures of representative politics in the ‘90s potentially fostered a desire in the working classes to take gentrification resistance into their own hands – to no longer outsource political power, but to harness and cultivate it from within the urban neighbourhood. In other terms, the decline of confidence in official forms of political representation produced a new generation of anti-gentrification art projects, which were initiated and driven by working-class communities. The general loss of faith in official political representatives seemingly cultivated a desire in working-class neighbourhoods to self-organise and to favour ground-level direct action over protest. Arguably, the working class in western metropoles experienced a ‘reversal of perspective’. According to Lovell, ‘to reverse perspective is to stop seeing things through the eyes of the powerful; it is to create a new vision of possibilities’ (Lovell, 2009: 90). A ‘reversal of perspective’ transpired in two major ways: firstly, ‘non-artist’ communities recognised their potential to initiate creative gentrification resistance; secondly, this took place within the working-class neighbourhood as opposed to the political sphere. The urban working classes stopped seeing the urgencies of capitalism through the ‘eyes of the powerful’, and began seeing them from the perspective of self-organised ground-level activism.

A Working-Class Turn in Anti-Gentrification Art Projects

With its radical ‘non-expert’ production process, Hafenrandverein’s (Harbour Edge Association) Park Fiction (1994 – ongoing) is a standout example of a successful and ongoing working-class anti-gentrification art project (Figure 1). This project was initiated in 1994 by St. Pauli’s working-class association and was later supported by artists/cultural agents Christoph Schäfer, Margit Czenki and Ellen Schmeisser (Thompson, 2012: 200). St. Pauli is a working-class neighbourhood in Hamburg, which has a significant history of everyday, bottom-up radicalism and dissent. The squatter movement, for instance, is a prominent highlight of this area’s history. In the early ‘90s, developers made a bid on a riverbank property in this neighbourhood and locals risked losing the only available space for public use. Park Fiction subsequently evolved out of this anti-gentrification campaign led by locals. Instead of protesting against the threat of gentrification, locals of St. Pauli began picnicking on the site as though it would soon house a public park. Although extremely quotidian, these picnicking activities kick-started a community-led planning process, which eventually deterred developer’s plans. The everyday, micro-level actions of working-class locals infiltrated urban development’s macro-level discourse, infusing it with accessible, participatory values. Harbour Edge Association maintained the working-class foundations of the project though their development of ‘special tools’, which kept the ‘non-expert’ planning process accessible to the whole community. These tools, which combined quotidian working-class urban experience with creativity, included a plasticine office, an ‘archive of desires’, questionnaires, maps, and a telephone hotline with an answering machine for those who got creative at night. The planning process was rendered game-like, encouraging co-production and negating gentrification’s exclusionary thematics. As artist and Marxist theorist, Guy Debord, argued years earlier, ‘the most pertinent revolutionary experiments in culture have sought to break the spectator’s psychological identification with the hero, so as to draw them into the activity’ (Debord, 1957 [2006]: 40–41). Corresponding to this statement, Harbour Edge Association produced a game board, which shared all of the playful ways that locals could maintain their centrality to the project. Park Fiction’s tools therefore supplemented the community’s anti-hierarchical rejection of the so-called ‘heroes’ of urban governance and ‘democratic’ politics. Mith these tools, St. Pauli’s working-class inhabitants were able to remain active agents of an accessible, ludic planning process.

It is interesting to consider the fact that the project took place in a major German city only a few years after the fall of the Berlin wall – an event, which supposedly signalled ‘the victory of capitalism over social alternatives of any sort’ (Burchardt and Kirn, 2017: 135). Remarkably, through the Park Fiction project, the locals of St. Pauli found an opening towards a horizontal, leftist urban programme at the height of capitalism’s victory over socialism. The insurrectionary, social-uniting aspects of Berlin in 1989 have been mirrored by this project. However, they have also been successfully combined with anti-capitalist resistance – something quite notable in light of the project’s socio-political context. On the subject of unity, whilst gentrification only unites those threatened with displacement in their separateness, Park Fiction has created a space for genuine social unity and community solidarity. As locals were united through a variety of collective, playful activities, the project has boldly mitigated gentrification’s fragmentary social effects. Social unity was also forged through a shared labour process between working-class locals and their supportive artist allies. Therefore, unity not only constituted the project’s end-goal (to create a free space for social unity), it was also vital to its production process. Through sharing resources and labour, urban public space was reclaimed as a shared resource in which locals could also be ‘in common’ with one another

Park Fiction also responded to gentrification’s tendency to delete local, ground level memories. Specifically speaking, an ‘archive of the people’ (the ‘archive of desires’) was formed, which memorialised the project’s working-class development process. This functioned as an effective counter-model to the official, power-serving forms of history and memorialisation that proliferate our cities, such as civic monuments of glorified historic figures, which are often used by city councils and developers as sophisticated tools to gentrify urban space (Boyer, 1983: 50; Deutsche, 1986: 20–21). Official history is opposed to everyday working-class experience. The former is often employed as a sophisticated way to censor the social urgencies of the latter in favour of urban image branding. As Deutsche (1986) highlighted, in his text Union Square (1933), novelist Albert Harper juxtaposed the ‘big history’, represented by the monuments in Union Square Park, New York, with the real ‘historical class struggle, whose skirmishes were then being waged within the square itself’ (Deutsche, 1986: 21). Correspondingly, Boyer stressed how, due to their association with order and moral perfection, neo-classical reproductions of Greek and Roman sculptures are often used in the public spaces of cities to uplift ‘the individual from the sordidness of reality’ (Boyer, 1983: 50). In Park Fiction, however, working-class urban experience trumped the potentially gentrifying representations and narratives of history. In collaboration with landscape architects, residents were also able to effectively bring to life the area’s most micro-level stories and hopes. For instance, a drawing made by a local boy in 1997 inspired the site’s now iconic artificial palm tree island. This could be described as a ‘social history’ approach, favouring the everyday urban histories of local peoples over the rarefied narratives of conventional history.

Social history can be defined as an approach to history that centres on the working class and everyday life. It is, in this sense, a radical negotiation of historicity, offering a ‘history from below’, which celebrates working-class quotidian experience (Evans, 2008). Social history is concerned with the quotidian rather than with abstractions, and with ordinary people as opposed to glorified individuals. Through its archival activities and commitment to memorialising local collective memories, Park Fiction mirrored the values of social history. The project’s ‘archive of desires’ memorialised the area’s alternative planning process so that subsequent working-class, grass-roots activists can reactivate it in the future, potentially using it as a go-to guide for resistance and dissent. However, by memorialising Park Fiction, the ‘archive of desires’ not only celebrated the dissenting working-class history of the project, it also functioned to remind the community that they could ‘make history’ rather than passively observing it. By reclaiming an area for social exchange unmediated by capital, Park Fiction favoured working-class ‘use-values’ of space over capitalist ‘exchange-values’. The directly lived nature of the park’s ‘use’ by working-class locals, countered the inauthentic, dehumanising nature of exchange-value, which reduces real social space into a mere representation. Neoliberal urbanism (‘urban entrepreneurialism’) and its gentrification processes, prioritise the exchange-value of space, transforming it into an ‘image-commodity’, which can only be ‘looked at’ by the urban working- class, whether it be privatised or caught in the machinations of speculative capital. These features of neoliberal urbanism are perhaps symptomatic of capitalist ‘spectacle’. The spectacle is a late capitalist economy in which our lives are no longer primarily defined by consumption, but by the passive reception of images broadcast by the media-economy alliance (Debord, 1967 [2014]). In Park Fiction, working-class usership has opposed the capitalist spectacle’s reduction of urban space into a series of image-commodities. Fundamentally, the project allowed for the undermining of speculative exchange-values by social, community-centred use-values.

Granby Four Streets (1998–ongoing) also aimed to replace neoliberal exchange-values with working-class use-values. This project grew out of a community’s twenty-year struggle against local governments’ attempts to demolish their homes. It provided a vehicle for residents of a neglected area in Liverpool to own assets and develop a thriving urban environment outside of the housing profit motive. Like Park Fiction, the residents of Granby in Toxteth, Liverpool, initiated the project. It was only further into the project’s development that the artist collective ‘Assemble’ came into the picture, simply supplementing the creative groundwork that locals had produced. Working-class people ‘commanded art for their community’, rather than, as is usual, ‘art commanding a community’ in the interests of power.Assemble did not enter the project as ‘elevated outsiders’ but as ‘sympathetic facilitators’, helping locals to achieve their agenda – to reclaim and renovate their homes. Assemble did not ‘parachute into the neighbourhood’ as paternalistic ‘saints’, to ‘rescue’ the community. Rather, with humility, they keenly supplemented, supported, and built upon, the creative anti-gentrification work already initiated and established by locals. Such an approach to the artist’s role in anti-gentrification resistance is vital because, as Graham argues, people living in precarious conditions, threatened with displacement do not want to be included in ‘sounding exercises or pseudo-consultations, visioning activities, engagement activities, or being told to ‘listen’. They demand to be heard in such a way that the inevitable story of gentrification can be altered’ (Graham, 2017: 47). The artist’s role is not rendered obsolete, but rather undergoes a transformation, which better aligns it with the progressive, social democratic ethics of urban art initiatives. The works addressed imagine a more ethical artist role in gentrification, whose involvement is centred on the working-class communities they are supposedly assisting. The working class defines the artist’s role, not the other way around. Artistic mediation is also reformed in projects such as Park Fiction. Instead of being pacifying, paternalistic, and colonising, artistic mediation in anti-gentrification art initiatives has supplemented already established working-class resistance and, in the long term, supports and facilitates it.

Granby Four Streets is, foremost, a working-class negation of housing’s irrational status as a ‘cash cow’ for speculative capital. Granby homes were not demolished for gentrification (the more profitable solution). Rather, they were restored and inhabited by locals who have reinstated their use-values as repositories of shelter, security, and community. Granby residents were also involved in decorating derelict houses, planting and crafting items for sale on the local market. The crafting of useful everyday items has been central to the Granby Workshop, which is run by locals and a member of Assemble. As a pre-industrial form of production, craft is conducive to the solidarity and self-organisation of the working classes. It is a potentially activating, creative labour, which tackles the non-intervention of capitalist consumerism. Granby has, therefore, become a rich site for producing useful objects, countering the passive consumption cycle that neoliberalism necessitates. It is perceivable that a community-centred ‘economy of use’ has been established in the area, further reiterating working-class ‘use’ over neoliberal exchange-values. The bureaucratic ideas of ‘public interest’ and ‘common interest’, which do not serve working-class people as much as they imply, have been replaced with ‘common needs’ (or ‘common use-values’) fulfilled by the community, for the community. With an established ‘economy of use’ operating through reclaimed homes, a monthly market and workshop, Granby has democratically managed its community’s ‘common needs’ following Assemble’s involvement. Around the mid-2000s, Granby locals started forming creative methods of everyday resistance such as planting, sitting at tables, redecorating boarded-up buildings, and developing their knowledge of housing laws. These everyday activities, which, in spite of their modesty, successfully problematised housing expropriation, could be understood as tactical subversions of urban space (Figures 2 and 3). As Granbyresidents engaged in activities not usually undertaken in spaces planned for redevelopment, they produced spatial ‘tactics’. Likewise, in Park Fiction, modest picnicking activities on a site planned for redevelopment became a means of occupation, which ultimately curtailed gentrification.

According to philosopher Michel de Certeau (1984), whilst ‘strategy’ is an instrument of power, ‘tactics’ belong to ‘the people’. De Certeau described ‘tactics’ as the means with which the proletariat ‘make-do’ with situations imposed on them by power. However, these everyday activities could also be considered spatial détournements. Détournement was a creative activity celebrated by a radical art collective, the Situationist International, in which capitalist cultural forms and meanings would be radically altered or misappropriated (Debord, 1959 [2006]: 67). Capitalistic media would be turned against itself, or have its significations negated altogether so that new, subversive meanings could be produced. As Granby Four Streets has encouraged activities not usually undertaken in spaces planned for demolition and redevelopment, it has arguably produced détournements of urban space. Likewise, in Park Fiction, modest picnicking activities on a site planned for re-development were fantastically transformed into a means of occupation, which prevented gentrification. Applying for Hamburg Department of Culture’s Art in Public Space’s programme, Park Fiction artists tactically acquired greater political influence with the city’s council, which still wanted to sell the site for building purposes (Rühse, 2014: 40). The Hamburg Department of Culture initially supported the project but withdrew funding with an official statement citing procedural difficulties. The consensus was that politicians did not want to be connected with critical activists. Nevertheless, to prevent mass social upheaval, the city finally made special allowances in 1997 (Ibid.). Artists in Park Fiction have, therefore, acted as ‘double agents’, finding loopholes in official practices, and potentially gentrifying city council art initiatives. Artists have mockingly used their status as ‘artists’ to manipulate urban governance and genuinely serve the demands of St. Pauli’s working class. The Situationists characterised détournement as a ‘real means of proletariat artistic education’ (Debord and Wolman, 1956 [2006]: 18). Correspondingly, in Park Fiction and Granby Four Streets, the détournement of urban space has been an accessible artistic strategy – a tool with which even working-class/non-artist communities have been able to problematise gentrification.

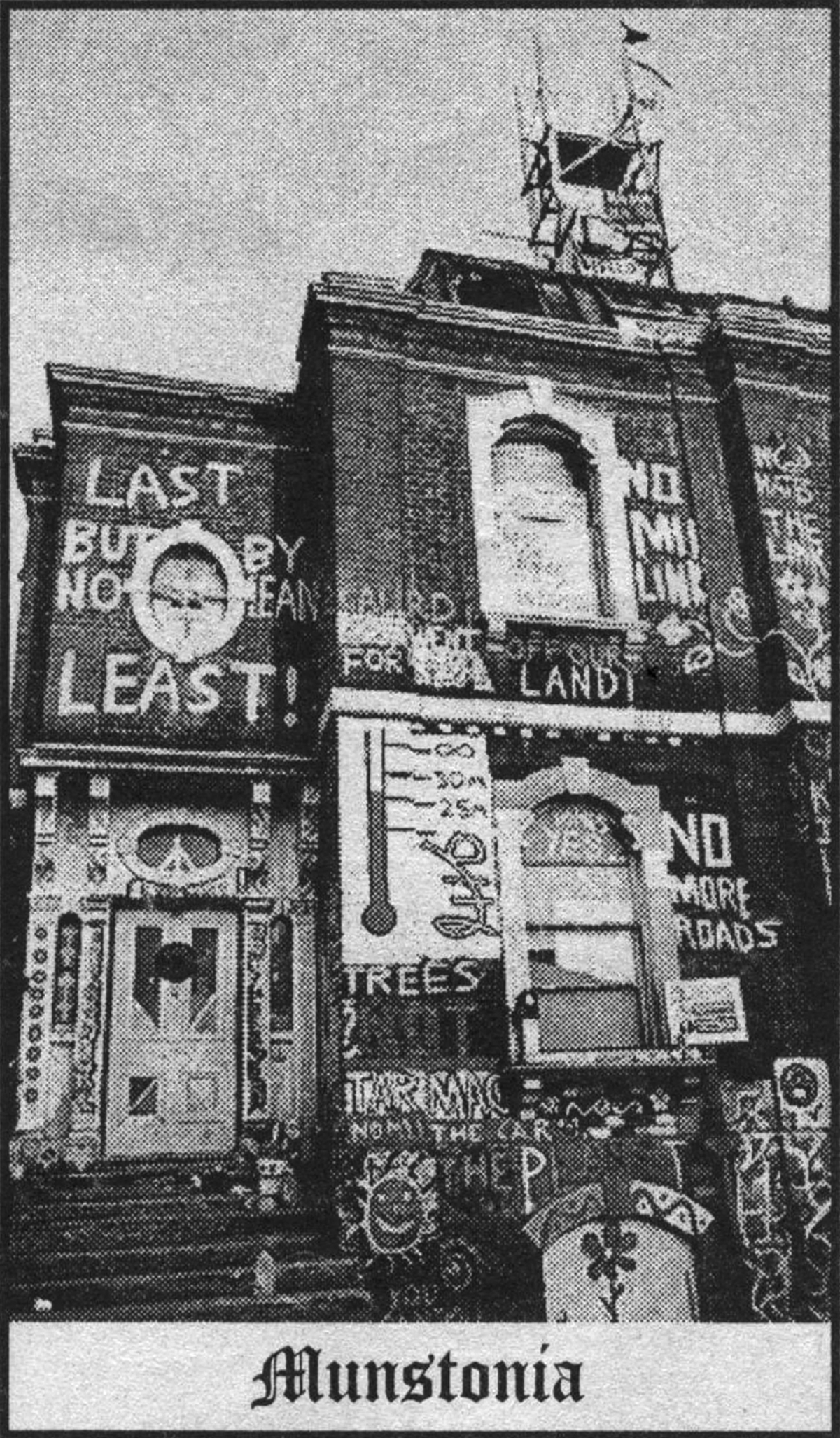

Claremont Road (1993–94) also harnessed the quotidian, proletariat activity of tactic and détournement. An army of residents, activists and artists fought against the development of an M link road, which would lead to the demolition and gentrification of Claremont Road. Over 18 months in the early ‘90s, anti-road protesters forged an anarchic occupation of the street, which was planned for demolition. The street was turned into a vibrant space to live, play, socialise, and even sleep. Unlike the previously cited projects, however, there was not a successful outcome, as homes were eventually demolished. Nevertheless, it is still an excellent example of how working-class communities have been active drivers of creative anti-gentrification resistance. Furthermore, because this project lasted several months, it caused significant delays to the road development. Many of the campaigners would also later re-emerge in the activities of ‘Reclaim the Streets’ (Blunt and Wills, 2000: 33). Similar to previous examples, quotidian actions functioned as powerful tactics or détournements, which disrupted the story of gentrification. During the ‘battle of Claremont Road’, furniture was moved out of homes and placed onto the street, laundry was hung out to dry, chess games were played on a giant chessboard, fires were lit, and parties were held (Jordan, 1998: 135). Residents painted cars, adorned the exterior walls of their homes with colourful designs, and gave each house a specific insurgent purpose (Blunt and Wills, 2000: 33) (Figure 4). However, the most powerful détournement in this project (as was also the case in the previous examples) was a ‘reversal of perspective’. Residents of Claremont Road, like the other everyday radicals addressed in this paper, stopped seeing things ‘through the eyes of the powerful’ and started to ‘create a new vision of possibilities’ (Lovell, 2009: 90). Locals reversed the standard top down perspective by treating urban space as what theywanted it to be, not what city council or developers wanted it to become.

Another interesting tactic used throughout Claremont Road’s working-class-driven production process involved sustaining urban ruin and decay. Locals elaborately decorated the deteriorating street and its houses, transforming them into impressive art installations. Many locals also locked themselves to rooftops, with nets hanging over the street, and many other dilapidated structures planned for demolition. Because it had sustained urban ruin and decay for an extended amount of time, Claremont Road represented a huge affront to capitalist urbanisation’s requirement for linear development and progress. Similarly, in Granby Four Streets, by sustaining their ‘urban ruin’ homes with painted decorations and plantings, residents successfully deterred gentrification. In both projects, the sustenance of urban ruin and decay problematised gentrification. However, in Granby Four Streets,it successfully kick-started a renewalprocess, which was decidedly bottom-up, community-driven and, most importantly, community-serving. The linearity of capitalist urban development and its gentrification processes was replaced by the more cyclical process of urban ruin and decay being resurrected from the ashes and given new life. The inclusion of ruin/decay in Granby Four Streets formed a cyclical development process that mirrored the pre-capitalist, uneconomic cycles of nature. This cyclical urban development process invoked a phoenix rising from the flames, which opposed gentrification’s linear process of demolishing and rebuilding from scratch – the preferred solution for profit seeking private and public entities. Aspects of renovated homes in Granby such as fireplaces, doorknobs, and tiles, were made from the wreckage of housing demolition (Granby Workshop, 2015). From the rubble and ruin of Granby’s neglected neighbourhood, a community-driven development process by the community, for the community, rose up.

Thesustainment of urban ruin and decay, as evidenced in both Granby Four Streets and Claremont Road, functioned in opposition to gentrification’s colonial rhetoric of hygiene, sanitisation, and order. City councils and developers view gentrification as a ‘civilising’, ‘purifying’, ‘sanitising’ process. Gentrification processes often use a language of ‘hygiene’ and ‘cleanliness’ to displace certain social groups (Campkin and Cox, 2012; Danewid, 2019). The exclusion of migrants and racial communities, for example, has been ‘central to the construction of ‘clean’ and ‘orderly’ streets’ (Danewid, 2019: 8). Within this context, spaces to be gentrified or expropriated are characterised as ‘dirty’, ‘unclean’, and ‘dangerous’. Urban ruin and decay have, in this sense, come to symbolise the disenfranchised and the working classes who city councils aim to ‘sweep away’, so to speak. Sustaining urban ruin and decay therefore becomes an obvious metaphor for the working classes countering the ‘cleansing’ and ‘sanitising’ actions of gentrification. Another creative working-class tactic against gentrification is ‘use’/‘usership’. Like the previous examples addressed, Claremont Road also harnessed the radical plebeian power of ‘use’, invoking De Certeau’s (1984) acclaimed hypothesis that usership offers radical everyday openings for working-class resistance. In Claremont Road, ‘using’simply involved occupying a residential street planned for demolition. ‘Use as misuse’ enables radicality to emerge out of banality (misusing a public park, misusing derelict homes and misusing an entire street planned for demolition). Park Fiction’s use of a space planned for gentrification as a public park was so banal that it was initially inconspicuous to urban governance. The socialising and urban planting in Granby was also inconspicuous and unthreatening. Use thus becomes a ‘direct action’ in everyday life whose radical power ultimately lays in its invisible, modest banality. Use’s plebeian banality endows it with a powerful invisibility to hegemonic forces. This unromantic, plebeian, and even ‘philistine’ nature of useful art, however, means that anti-gentrification resistance can ‘go unnoticed’, avoiding the interference of power.

The various uses or ‘misuses’ of urban space that have featured in the addressed projects have illustrated how ‘use’/‘usership’ threatens the notion of expertise/expert culture. Use has been central to anti-gentrification art projects initiated by working-class communities, as it is immediately available and something that is so radically ‘anti-expert’. Integral to everyday life, use and usership are not the special property or initiative of power or privilege, or some elevated, inaccessible form of activity (Wark, 2013: 10). ‘Usership’ is placed in diametrical opposition to ‘expert culture’ (Wright, 2013: 468). In truth, there is no one particular way in which something must be ‘used’, and therefore, ‘use’ strips away expert culture’s veneer of specialised, elevated skill, highlighting openings for working-class, ground level action. It is a remarkable fact that pedestrian uses of urban space such as, planting, painting, and hanging out laundry etc., have come to represent, in the addressed projects, that which initially disrupts gentrification. Everyday working-class uses of urban space in Park Fiction, Granby Four Streets and Claremont Road, have arguably disrupted gentrification because they expose the irrational logic of valuing capitalist exchange-values over basic human needs and rights. In other words, in actively demonstrating the ways in which urban space has clear and fundamental use for an entire community, the unjust nature of the profit motives behind expropriation and dispossession are brought to light. Ultimately, use speaks of the invisible ‘power of the people’, of the invincible agency of the working class to ‘use’ urban space in whatever way they wish.

Conclusion

This paper has examined the importance of working-class communities in anti-gentrification art projects within the last 30 years. It has argued that working-class agency has been vital to anti-gentrification art projects – especially since the ‘90s. During this decade, neoliberalism, urban entrepreneurialism, and a decline in structured forms of political representation, seemingly fostered a working-class desire for self-organisation and direct action. It has been observed that, in the mid-‘90s, urban working-class communities gained significant authorship rights in anti-gentrification art projects, becoming active initiators and ‘non-artist’ agents. Mithin this configuration, artists were no longer rarefied cultural producers, but rather, ‘supportive facilitators’ of working-class agendas, sharing their authorship with communities. Artistic mediation, on the other hand, has become ‘supportive’, ‘supplementary’, and ‘activating’. The theoretical implication of this research is that contemporary art scholarship needs to place the urban working class, as opposed to the artist, at the centre of its discursive attention. In the examples addressed, working-class communities have not been ‘shown’ or ‘told’ what to do by art’s paternalistic, colonising arm, but rather, have directed their own thrilling stories towards brighter urban futures.

Amy Melia is an art historian, urban arts researcher, writer, and educator who is in the final stages of her PhD at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU). Funded by LJMU’s PhD scholarship award, her research examines what she calls an ‘urban social aesthetic’ tendency in contemporary art – a category of practice characterised by a direct engagement with urban social urgencies as a vital means for anti-capitalist resistance. Amy has presented her research at several international conferences across the UK and Europe, including Urban Creativity (Lund, Sweden) and Arts in Society (Lisbon, Portugal), and she has featured on the ‘Art and Gentrification’ panel at the 2019 Association of Art Historians conference (Brighton, UK). Amy has also published her research in international journals and is currently contributing a chapter to a forthcoming publication called Art and Gentrification in the Changing Neoliberal Landscape. She is also a sessional lecturer on LJMU’s BA (Hons) History of Art programme and a ‘Brilliant Club Tutor’, teaching in secondary schools in the North West of England. Her ongoing research into the anti-capitalistic tendencies of urban art initiatives has also been published in international journals. She is a Sessional Lecturer on LJMU’s Art History programme and a ‘Brilliant Club Tutor’, teaching in secondary schools in the North West of England.

- 1

Gentrification can be defined as the ‘the transformation of a working-class or vacant area of central city into middle-class residential and/or commercial use’ (Lees et al., 2008, xv).

- 2

Stephen Wright’s Lexicon of Usership (2013), in: Aitkens et al. (eds.) (2016) What’s the Use? 468–487. 1:1 scale art is artistic production, which works directly with its subject matter instead of representing it.

- 3

Park Fiction: http://park-fiction.net.

- 4

Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1967).

- 5

Granby Four Streets CLT: www.granby4streetsclt.co.uk.

Blanco, J. R. (2018) Artistic Utopias of Revolt: Claremont Road, Reclaim the Streets, and the City of Sol. London; New York, NY: Palgrave.

Blunt, A. & Wills, J. (2000) Dissident Geographies: An Introduction to Radical Ideas and Practice. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

Boyer, C. (1983) Dreaming the Rational City: The Myth of American City Planning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Burchardt, M. & Kirn, G. (eds.) (2017) Beyond Neoliberalism: Social Analysis After 1989. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Campkin, B. & Cox, R. (2012) Dirt: New Geographies of Cleanliness and Contamination. London: I.B. Tauris.

Courage, C. (2017) Arts in Place: The Arts, the Urban and Social Practice. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

Danewid, I. (2019) ‘The Fire this Time: Grenfell, Racial Capitalism and the Urbanisation of Empire’, European Journal of International Relations. [Online] Accessed December 13, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066119858388.

Debord, G. & Wolman, G. (1956) A User’s Guide to Détournement, in: Knabb, K. (ed.) (2006) Situationist International: Anthology. Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets, 14–21.

Debord, G. (1957) Report on the Construction of Situations, in: Knabb, K. (ed.) (2006) Situationist International: Anthology. Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets, 25–43.

De Certeau, M. (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Deutsche, R. (1996) Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Deutsche, R. & Ryan, C. G. (1984) The Fine Art of Gentrification. October, 31: 91–111.

Duncan, P. J. & Schimpfössl, E. (eds.) (2019) Socialism, Capitalism and Alternatives. London: UCL Press.

Evans, E. (2008) Social History. [Online] Accessed January 22, 2020. https://archives.history.ac.uk/makinghistory/resources/articles/social_history.html.

Graham, J. (2017) ‘A Strong Curatorial Vision for the Neighbourhood: Countering the Diplomatic Condition of the Arts in Urban Neighbourhoods’. Art and the Public Sphere, 6(1–2): 33–49.

Granby Four Streets CLT (2014) ‘History of the Four Streets’. [Online] Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.granby4streetsclt.co.uk/history-of-the-four-streets

Granby Four Streets CLT (2014) ‘Granby Four Streets CLT’ [Online] Accessed: January 16, 2020. https://www.granby4streetsclt.co.uk.

Granby Workshop (2015) [Online] Accessed January 16, 2020. http://www.sharethecity.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/15-10-07s-Assemble-Granby-Turner-Prize-Workshop-Catalogue.pdf.

Harbour Edge Association (2013) ‘Park Fiction – Introduction in English’ [Online] Accessed January 13, 2020. http://park-fiction.net/park-fiction-introduction-in-english/.

Harvey, D. (1989) ‘From Managerialism to Entrepreneurism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism’. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 71(1): 3–17.

Jordon, J. (1998) ‘The Art of Necessity: The Subversive Imagination of Anti-Road Protest and Reclaim the Streets’, in: G. McKay (ed.) (1998) DiY Culture: Party and Protest in Nineties Britain. London, Verso, 129–151.

Lovell, J. S. (2009) Crimes of Dissent: Civil Disobedience, Criminal Justice, and the Politics of Conscience. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Miles, M. (1997) Art, Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Pritchard, S. (2019a) ‘Place Guarding: Activist Art Against Gentrification’, in: Courage, C. & McKeown, A. (eds.) (2019) Creative Placemaking: Research, Theory and Practice, Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

Pritchard, S. (2019b) ‘More Today Than Yesterday (But Less Than There’ll Be Tomorrow)’. Nuart Journal, 2(1): 10–20.

Rosler, M. (1991) ‘Fragments of a Metropolitan Viewpoint’, in: Wallis, B. (ed.) (1991) If You Lived Here: The City in Art, Theory, and Social Activism, A Project by Martha Rosler. Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 35–6.

Rühse, V. (2014) ‘Park Fiction – A Participatory Artistic Park Project’. North Street Review: Arts and Visual Culture, 17: 35–46.

Thompson, N. (2012) Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991–2011. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wald, M. (1998) ‘Unionism in the 90s’. Monthly Labour Review, 121(2): 70.

Wark, M. (2013) The Spectacle of Disintegration: Situationist Passages Out of the Twentieth Century. Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

Wright, S. (2013) ‘Toward a Lexicon of Usership’, in: Aikens, N., Lange, T., Seijdel J., Ten Thije S. (eds.) (2016) What’s the Use? Constellations of Art, History and Knowledge, Amsterdam: Valiz, 468–87.