This research article examines the subcultural media practices among a group of male graffiti writers in the city of Helsinki, Finland. It builds on Jeff Ferrell and Robert Weide’s ‘spot theory’ and focuses on letter-based graffiti writing on trains. The object of this study is to articulate how local graffiti writers, who take part in the city’s spatial subcultural play, use subcultural media for the purpose of ‘spotting’ and boundary making. It concludes that seeking respect and prestige in the local community is not always achieved by way of acquiring visibility or ‘fame’, or through the proliferate circulation of graffiti painted trains on different media channels. The article is based on the findings of a long-term ethnographic fieldwork project (2011–2018) carried out in Helsinki.

Introduction

At 6 AM, it was still dark and freezing. So, we were waiting at the station; the train was supposed to arrive in ten minutes. The guys looked tired and serious; they were dressed in black and sported hoodies. They were looking at the ground, avoiding the CCTVs. I did the same. The train arrived. ‘Fuck, it’s the wrong train!’, one of the guys responded, and I saw nothing on the train. ‘Let’s check if it’s the other train; can you see the [graffiti] pieces on the other side?’ The guys stretched their necks, looking through the windows, but it was dark and, at least, I couldn’t see anything ‘on the other side’. ‘Was it that one? Fuck it wasn’t!’ ‘I couldn’t see anything.’ ‘Did it have three carriages?’ ‘Did you see if the first two wagons had waves on its side?’ ‘Yeah, it wasn’t that one for sure.’ ‘Fuck if they’d pulled it out of service.’ ‘Don’t think so, they wouldn’t have time. For sure that’s the one they took out from the yard, that’s the one that leaves first.’ The guys had reckoned it wrong. I said nothing, just followed them out from the station. ‘Next one [train] will be in 20 minutes.’ (Fieldnote, 2012)

This fieldnote was written after a fieldwork trip with a group of male graffiti writers in Helsinki, Finland. The night before, two different commuter trains standing at a station had been painted, and we were supposed to ‘spot’ these trains in traffic as part of the post-spray painting ritual of documenting the short-lived graffiti while in circulation. It is simply deemed cool to have a photo made in traffic. This essentially meant taking photographs in some place at a station or along the track that offered enough of a view to ‘catch’ the passing trains. It was crucial for the writers to spot these trains because none of them had proper photographs of their pieces. They had painted in a narrow aisle between the trains in the darkness of night, and in those hours, producing a satisfactory photo of their graffiti pieces was apparently challenging. It was also important to catch these trains during the morning’s first rush hour as graffiti covered trains are taken out and sent into the ‘buff’ after only a single round of service due to the zero tolerance policy employed by the Finnish railway company VR.

In this article, I apply a methodology I call ‘spotting trains’, influenced by Jeff Ferrell and Robert Weide’s (2010) spatial analysis called ‘spot theory’. Spotting trains reflects both the creation of visual documentation as well as the physical movement, i.e. The writer’s chase of the train in its movement (see Figure ). The documentation and the chasing of the train are a form of subcultural play and demonstrate graffiti writers’ sense of the local subcultural idioms and the specific landscape of train writing in ‘the cities in the city’ that alter the dominant approach to the legislated city (Young, 2014). The preconditions set by the spatial dimensions in the city’s train system, the policy of the train company, and the subcultural value of getting a train photographed in traffic all contribute to the graffiti writers’ specialist knowledge of the circulating trains. Thus the ‘spotting’ is not only a subcultural skill for selecting an appropriate ‘spot’ for graffiti writing (Ferrell & Weide, 2010: 49), but a further engagement with the spot by regularly extending its spatial dimension through pictorial re-representations. Spotting therefore becomes a powerful source to mediate, transform, and promulgate subcultural spots that physically appear as temporary and ephemeral, often as a result of control policies, most notably the zero tolerance policy under which graffiti is quickly removed from urban space.

This article is at the theoretical intersection of subcultural theory and cultural criminology, and addresses their overlapping interest in the making and the control of subcultural and mediated urban spaces. The resulting interdisciplinarity occupies a field which seeks to extend the boundaries of spatial knowledge employed in subcultural meaning and value making. Subcultural theory engages the exploration of contested meanings with regard to deviation from, or resistance to the conventional and the dominant, often referred to as the mainstream (Hannerz, 2016: 52; Thornton, 1995); yet, it also shapes the structural significance of the ‘subcultural subject’, while recording the rhetoric of social privilege and hierarchy within certain spatial contexts (Blackman & Kempson, 2016: 10; Jensen, 2018). While subcultural theory has a long history and has developed as a dialectic of differing paradigmatic schools, cultural criminology is a fairly new subfield. Established partly as a critique on positivistic criminology, situational crime prevention, crime mapping and, moreover, the broken window model of zero tolerance, cultural criminology has come to participate in the alternative ways of interpreting the relationship between space and crime by recognising cultural and mediated dimensions often overlooked by these simplistic methods of crime control (Hayward, 2012: 441; 2009).

This research article embraces urban fieldwork and notions of edge ethnography used in cultural criminology (Ferrell & Hamm, 1998). Ethnographic research in cultural criminology is profoundly engaged in situated dynamics, emotions, and meaning in everyday life within particular (sub)cultural milieus (Ferrell, 1999: 399). Conducting ethnography in illicit subcultures often requires researchers’ participation and deep immersion in order to produce a multifaceted knowledge of the studied field. Being in such a position, the researcher becomes a part of the generated research knowledge and, as such, requires at least a partial understanding of one’s own positionality within the field. Blackman and Kempson (2016: 10) stated that ‘this realisation requires the development of innovative methodologies that are equipped to offer multiperspective views on researcher/participant relations, and on the process of identifying which findings are ‘significant’’. Methodologies of both cultural criminology and subcultural studies often combine urban ethnographic participatory observation with media content analysis, using research particularly at the intersection of media, crime control, and subcultures (Ferrell, 1999: 400; Hayward, 2009; Thornton, 1995). It is here that urban ethnography is able to find a context that imposes creativity, transgression, and collective solutions among members in subcultures controlled by a city’s policy. Furthermore, ethnography is a research design whereby the research questions often emerge as the methodological practice goes along. It was precisely by participating in graffiti writers’ photographing practices, ‘spotting trains’, that I became interested in how graffiti writers publish train graffiti and how they use different subcultural media for the benefit of their own train writing missions. Thus, this article addresses some of the subcultural publishing logics with regard to visibility and the way in which visibility is involved in boundary making inside the graffiti subculture, focusing on those claiming ownership of an itemised subcultural landscape, or more specifically, ownership of particular spots for train writing.

This research article stems from a long-term ethnographic research project conducted in Helsinki (2011–2019). I have applied multiple sets of different participatory observation methods for different graffiti writers and street artist groups, including participant interviews and the analysis of different graffiti-focused micromedia. In this article, I address the subcultural media practices of a distinct all-male group of graffiti writers in Helsinki engaged in the practice of train writing. Train writing can be defined as a genre of graffiti subculture dedicated to spray painting passenger trains, freight trains, and subway carriages, and is based on both the classical letter style and the practice of name writing in public space. With reference to its historical roots in the New York graffiti youth culture that emerged in the late 1960s, train writing is often presented as the fundamental act of graffiti subculture (Austin, 2001; Stewart, 2009), which is known for such concepts as manliness, being ‘real’, and striving for hegemony within the scene (Macdonald, 2002).

The first intensive observation period in this rather loosely organised community of graffiti writers started in August 2011 and lasted until February 2013. Subsequently, I kept following some of the members of this group and finally conducted six in-depth interviews in 2018–2019. These taped interviews varied from one to three hours and were semi-structured by themes, such as ‘graffiti and media’, ‘zero tolerance policies’, ‘Helsinki graffiti’, and ‘gender in graffiti’. The analysis of this article focuses on the themes that arose as significant in the process of spotting trains and in relation to the media practices among these graffiti writers. The analysis is based on fieldnotes and the thematic interviews, as well as local graffiti magazines, books, and online digital media that deal with graffiti in Finland. Before moving on to the ethnography of this article, I will first outline the concept of an ecology of spots by revisiting Ferrell and Weide’s idea of spot theory.

The Ecology of Spots

Ferrell and Weide’s (2010) ‘spot theory’ maps graffiti writers’ conceptions of spatiality in the city and the ways they choose significant spots in which to paint. As a starting point, they argue that the collective motivation for spot selection is recognition and prominence among other writers and city residents, and as such, each act of graffiti writing involves a trade-off between the factors of visibility, location, and risk. Ferrell and Weide (2010: 51) maintain that graffiti writers seek an audience in order to increase their subcultural status and acquire fame, which is a widely accepted idea in the research of the graffiti subculture (Bloch, 2019; Castleman, 1984; Lachmann, 1988; Macdonald, 2002; MacDowall, 2019; Snyder, 2009). Fame refers to the graffiti subcultures’ own prestige economy of ‘getting up’ and the labour involved in maintaining a presence in a city’s spatial dimensions. Austin (2001: 40–43) stated that fame, in the early 1960s writing culture of New York, was an alternative route for poor, racialised youth to exist and to manufacture a name in the city’s complex economy. Other previous studies on graffiti subculture have constructed the fame game as an alternative, deviant career path; a social ladder that has been described on the basis of a number of similar overarching distinctions: toy to king (Castleman, 1984: 77), toy to muralist (Lachmann, 1988) or graffiti writer to graffiti artist (Stewart, 2009: 83), presenting the outcome of a path that leads to cultural recognition in the mainstream art world, while simultaneously provoking tensions for remaining underground and subcultural. Later studies have contributed to the graffiti career approach, and the fame hunt has been affiliated with a self-concept for constructing a masculine identity (Macdonald, 2002) or a route for career paths in creative labour, while challenging class-analytic subcultural theory (Snyder, 2009: 171).

Choosing spots is thus directly linked to the substance of fame, as visible spots become resources for subcultural credibility. However, Ferrell and Weide (2010: 56) note that spots are clearly not fixed or denoted as static urban locations, but are always situated in the city’s complex changing physical ecology. Especially in the genre of train writing, the connection between the painted spot and the viewed spots may be disrupted, as the moving object is often painted somewhere other than where it is viewed in the city’s transit system. Trainyards, layups, and terminal stations may act as spots, yet they are constantly in a changing process; trains are pulled in and out, cleaners come and go, and there are surveillance cameras operating in the area. As such, patterns of different entrepreneurs, urban policing, graffiti removal, and private security interfere with writers’ ongoing struggle to get status and visibility. This specialised knowledge of the changing spatial dimensions is elsewhere recognised as subcultural ‘skills’ accumulated by the social community of writers with its shared goal orientation (Austin, 2001: 64–65). Graffiti writers internalise the rhythms and pulses of the city in order to access and master spots. In this way, according to Ferrell & Weide (2010: 57), spots are understood as liquid, as they are constantly subaltern to the city’s ecological and social malleability.

As a creative subcultural resistance against the removal of graffiti from public space, Ferrell and Weide point towards the rise of graffiti media: subcultural micro-media, photographs, magazines, videos, and online media channels have altered the earlier prestige system of writing, as they have provided new subcultural spots for recognition and visibility (see also Austin, 2001: 249; Snyder, 2006). Spots become further liquefied by the increasing use of digital media and material uploaded to the internet, which disconnect the physicality of the spot and its traditional subcultural status rooted in maximum street visibility. Here, they state that the interplay between what they call urban spots and mediated spots is not only circulated globally, but circles back on their sources in a way that challenges the distinctions between source and simulation (Ferrell & Weide, 2010: 59). Current graffiti studies focusing on digital and social media present a shift insofar as they define the fame game not as a straightforward process, and they raise awareness of the fact that there are differences in fame in relation to particular media, such as the ‘instafame’ earned online which invokes a more genuine reputation earned offline or in analogue media (MacDowall, 2019). As such, various media also confront the essence of fame beyond a simple visibility linked to spatiality, and bring out new complexities and different meanings for fame. More-over, they contribute to the subcultural difference, as different subcultural media come to present different meanings in relation to each other and to what could be understood as the mass media or mainstream media (Thornton, 1995; Hannerz, 2016).

The ‘liquidity’ of spots displayed in the wide range of media aligns with ideas of a postmodern hyperreality accompanied by a strong emphasis on agency. As such, the subcultural terrain appears as fluid, uncertain, boundless, creative, and liberating. However, despite being constantly reshaped by human action, urban space is never free from structural inequalities and social divisions (Joseph, 2008). Although Ferrell and Weide’s article describes how the patterns of spots get altered by public authorities, it does not extensively explore the patterns of unequal access to spots or how writers become able to choose urban or mediated spots beyond simple fame seeking or applying writers’ moral codes (Ferrell & Weide, 2010: 54). Spots – urban or mediated – are not just liquid but bound to and shaped by the city’s physical, cultural, and social order. Crucial for spotting and the interplay with spots are the cultural and social conventions with regard to the able-bodied, which relate to gender, race, and social class, and shape the ways in which writers gain access to spots or are able to stroll through the city. Bodily capacities which allow to get to hard-to-reach spots, to move in and out of specific places, and to be able to escape from risks and dangers, are integral to the practices of graffiti writers, but are also built on the normative notion of an able, white male body (Hannerz, 2017: 374–375; Macdonald, 2002). Moreover, the ability to avoid control and having access to spots is granted to bodies that are able to ‘pass’ unnoticed in districts or in moments of the city, often excluding racialised or gendered bodies from its space (Hannerz, 2017: 275–376). Yet, passing some place unnoticed and the overall mobility between the spots – such as travelling from one city or country to another – also involve notions of social class and economic resources necessary for such mobility.

Rather than proposing a spatial uncertainty of mediated spots, I suggest that graffiti photos and videos, as outcomes of spotting, play an important role in mapping the city’s subcultural landscape and regularly function as a resource for graffiti writing. The archives of mediated spots decentralise the topographic information earlier controlled by able writers living nearby. Spots become known through the enormous archives of mediated information and are conceptualised by writers who have never visited the spot physically. Yet, spots, as a resource for subcultural play, are bound to municipal policies, and limited resources do not always serve a perspective of subcultural fame seeking, as media attention may invite ‘others’ to visit the spot. Thus, in the city’s complex ecology, media easily become a meeting point for different social representations, and channels for micromedia are no longer relegated to narrow subcultural circuits in the way underground DIY-fanzines perhaps used to be, as many now have the ability to publish and create micromedia online. The increasing use of digital devices gives random passers-by, visiting graffiti writers, or graffiti admirers the opportunity to post graffiti online, while challenging the unified publishing logics set in localities or in subcultural divisions. This constant interplay between urban and mediated spots and between opposing media practices may enhance boundary making, and may also construct dialogues, negotiations, and conflicts in an ecology of spots.

Spotting Trains and Articulating Publishing Logics

‘Did you get ‘em?’, Janne asks before we even greet. He is out of breath. ‘Yes, I’ve got them.’ ‘Were they good?’ ‘Well, look for yourself.’ Janne inspects the photos for ten minutes. I thought the photos were good, but Janne criticises his [graffiti] piece. ‘Check out that line, it should not go like that. Now it’s bollocks!’ I could not believe how self-critical he was, but he said that there was always room for improvement. (Fieldnote, 2012)

My presence in the all-male group became more or less accepted as the writers realised that I was useful in photographing their graffiti paintings on trains while the art pieces were still ‘running’ in traffic. Moreover, being female perhaps put me in a better position to photograph graffiti-painted trains at a close distance and circumvent the surveillance of guards, train drivers, and conductors who occasionally would confront my male informants at the stations. During the first observation period (2011–2013), I met these writers two to three times per week, from six hours up to 24 hours per meeting. Often, the meetings involved swapping SD cards with pictures of train panels, discussing the last train writing mission, and planning the next one. Janne, like all the other writers I followed in this community, had several years’ experience of train writing, and most of these writers had started writing graffiti in their early teenage years. They were active train writers committed to the time-consuming activities of scoping out train yards, planning ‘missions’, and spotting trains. They took their train writing seriously, and this meant not only performing strictly planned and strategic train actions, but also making sure there would be good documentation of the actual graffiti pieces; the ‘panels’, ‘top-to-bottoms’ or, at times, even ‘whole carriages’.

From 2011 to 2013, the group consisted varyingly of ten white males aged between 20 and 30. Generally, this was a group whose members had had limited schooling and ‘drifted around’. Many of the informants were unemployed, a few were taking vocational courses, and some had short-term jobs in industry, construction, logistics, or manufacturing. Additionally, some of the graffiti writers faced serious outcomes from police investigations that had resulted in several convictions and huge claims for damages from the railway company VR and the Helsinki Regional Transport Authority (HSL), which – considering also their low income – clearly put them in a perilous social position. These graffiti writers were not developing artistic careers and did not have jobs on the market for creative labour, despite being well-known and respected in the local graffiti scene. Rather, they had remained in the male-dominated working-class sector of society, and by 2019, only two of them had pursued higher education since the first observation period. I consider these writers to be part of the precariat class, even though they rarely articulated a clear class position for themselves.

Indeed, contemporary class formations are complex, but class consciousness seems to be troublesome for young people in these times of neoliberalism, which tends to emphasise the role of the individual, rather than articulate belonging to a social class (Jensen, 2018: 410–411).

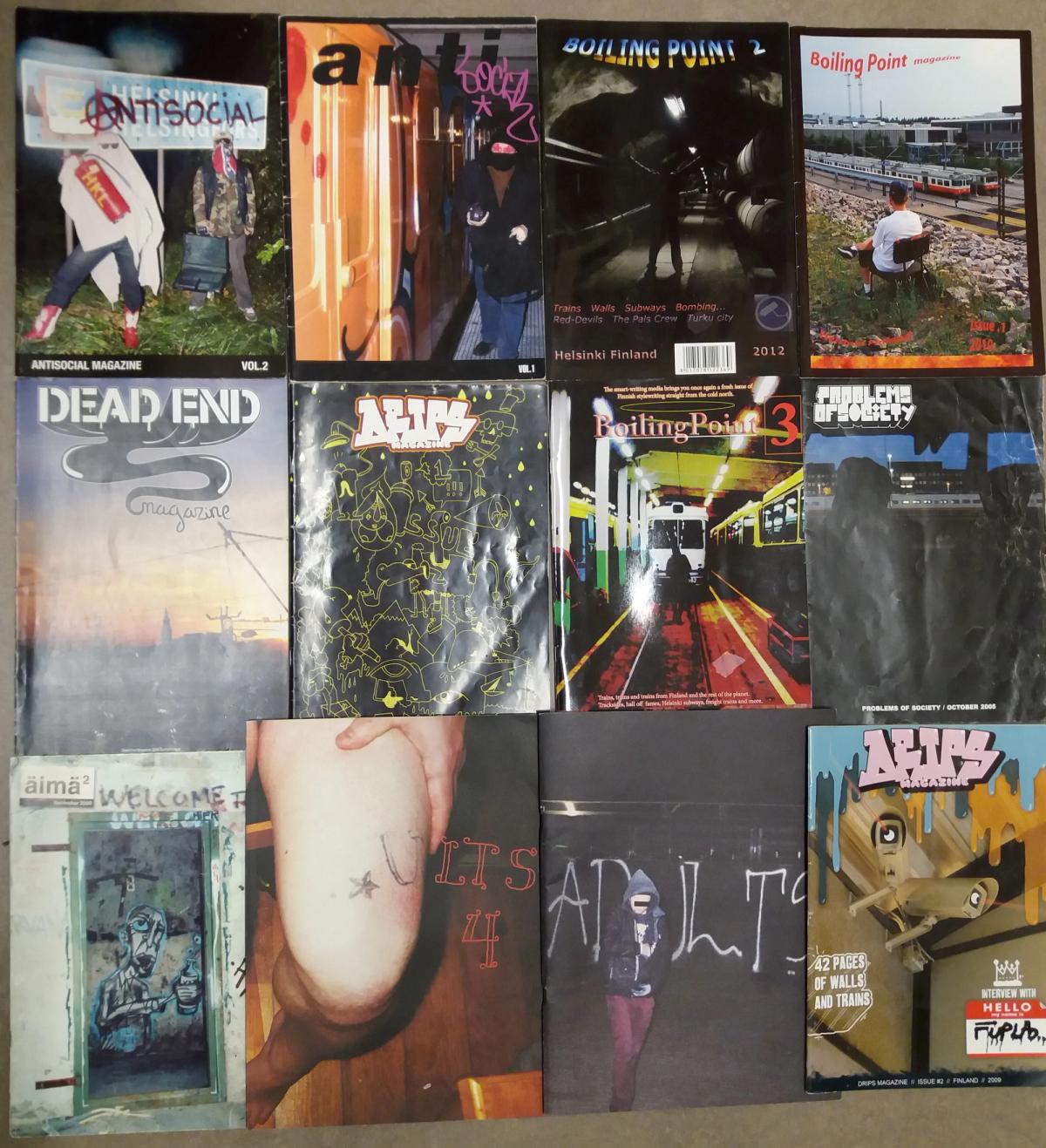

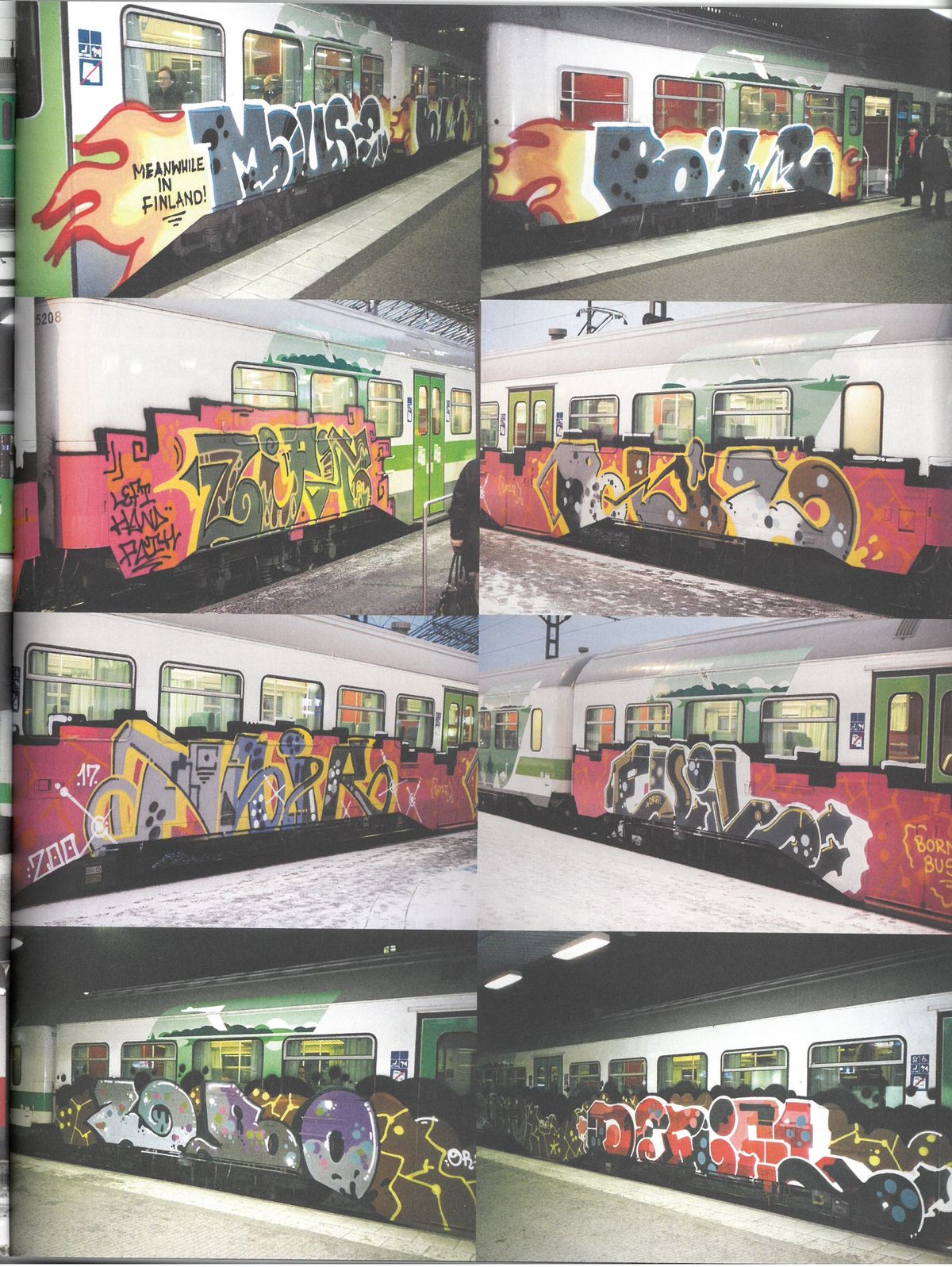

Participating in spotting and documenting train graffiti allowed me to gain a perspective on the subculture’s publishing logics, and on the ways this shaped some of the focal points within the community. The face-to-face interaction and trading of graffiti photos generated complex informal rules of what constituted a presentable photo, but most importantly, it helped decide who has the right to publish and on which media platforms. Some of the spotted trains that I witnessed were published in local graffiti magazines, yet countless graffiti pieces on trains were never published, and almost none were published online by the graffiti writers themselves. Perhaps the main goal for these writers was not to claim fame, but to be able to govern the circulation of one’s own graffiti photos, for there was a difference as to where these photos were supposed to be published. Most of the writers preferred to publish their photos in local graffiti magazines, as these were considered the exclusive platforms for presenting a selection of ones’ achievements (see Figure 2). Finnish graffiti magazines contain mainly visual content – i.e. images of graffiti – and rarely include any articles (see Figure 3). Submitting a photograph to a graffiti magazine was guided by two principles. First, who painted the train, and second, who took the photograph. If a writer had spotted another writer’s train piece, it was generally not acceptable to publish it without the consent of the author. Sometimes this did happen, however, triggering conflict inside the community:

Kari was raising his voice: ‘Who gave you the permission to send in that photo?’ Niko answered nonchalantly: ‘I don’t need a permission, it’s my photo. I took the photo.’ (Fieldnote, 2013)

Crucial in terms of their use, the ownership of an image is defined both by the producer of the photograph and the writer behind the graffiti piece. Some writers claimed ownership of images because of the hard work that was required to take the photo: ‘He didn’t have the guts to go to the station, whereas I did’ or ‘No one else turned up that morning’. Others dictated ownership in terms of content, with writers sometimes editing photographs of graffiti pieces in case consent was not received from all: ‘Better to cut his piece out’.

Another often discussed topic was images considered ‘too hot’ to be published; some photos contained important time-spatial information that is useful for acquiring subcultural skills required for the practice of train writing, and in this way, they proved to be significant learning tools. For instance, analysing a bunch of photographs in magazines allowed for the construction of spatial patterns, such as one writer’s development of photographing styles, or typical places where he/she usually took photographs of trains in traffic. The circulation of trains on different lines could be identified on the basis of stations or architecture recognised from a photo, which in turn helped to find potential loopholes for painting trains on specific lines. If the photo appeared to have been taken inside a train yard, the possible location could be recognised by looking at the train models and particular features in the back-ground, such as fences or other specific objects. Graffiti writers have, as already noted, a special ability to discern the infrastructural patterns within a city and this sometimes motivated my informants to search for new and innovative spots for taking photographs, which were not typically known among their peers:

The photo of the ‘top-to-bottoms’ was taken in unfamiliar terrain: the old commuter train was riding over an old bridge. Nobody was able to recognise the place, and everyone was asking ‘Where did you take this photo?’ ‘Won’t tell you!’, Kari laughed. (Fieldnote, 2013)

Additionally, the time a photo was taken was measured by analysing its lighting. Was a photo taken in broad daylight, or during the first rush hour in the morning? Were there any signs of winter, or rather of a summery white night? The ability to read the photos was thus an important factor in producing subcultural knowledge and obtaining substantial information for local train writing.

Some of the magazines had ‘open calls’ on Facebook pages or Instagram accounts; however, others collected photos only during personal encounters. The local graffiti magazines displayed various local graffiti styles, and the train writers would often rank the magazines against one another. Some magazines were more train oriented, whereas others also included sections of walls and street bombing. The graffiti magazines were also quite often considered as biased as a result of editors favouring certain graffiti writers. This was explained in an interview with one of the informants:

I think, in any graffiti media, whether it be a book, a magazine, or a video, they’re always slanted. And, if you look at Finnish graffiti magazines, they’ve always given you a wrong picture. Hell no are they true, and the author is always recognisable, who’s done it, what crews he has, it’s really interpretable. (Niko, 2019)

However, this could also be realised as a promising issue:

For me, the thing is that the magazine itself is also a piece of art, and I don’t want to have a [graffiti] piece catalogue. For magazines can’t have an objective representation of a scene, can they? I would rather publish in a magazine that has more quality and where my piece is among the best ones. For example, I don’t want to publish in X, because it’s published too often and that’s why it has a bad filter. (Aleksi, 2019)

In these comments, Niko and Aleksi pointed out two contrasting ideals for graffiti magazines, where one proposes an impartial truth of the subcultural landscape – that is, representing the diversity of graffiti seen in the urban space from the wide range of different artists in the city. The second view proposes a subjective perspective of the scene, presenting graffiti from specific cliques often associated with the editors of graffiti magazines. Similarly, Austin (2001: 260) recognises the editors’ powerful role in the subculture, and that ‘getting up’ in a magazine may be more dependent on who a writer knows than on his or her talent. The editors of various graffiti magazines are thus recognised as important actors in the process of subcultural construction, and magazines contribute to subcultural boundary making by highlighting the ones who get published – often those graffiti writers who have already established a name for themselves in the city. On the other hand, the magazines might present up-and-coming crews and younger writers performing in a favourable style; thus, they also mark generational changes in the subcultural landscape.

Exploring Mediated Spots

Online publication has clearly marked a rapid change in the subculture’s characteristics, especially in its ability to bring different city dwellers into a common space of communication. Generally, the observed writers were sceptical of online publishing, and they avoided publishing online themselves. Despite avoiding publishing online, they were all following various digital platforms administered either by other graffiti writers or by graffiti admirers who publish graffiti from a wide range of different artists. During the first observation period (2011–2013), Instagram was not yet widely used in the local graffiti subculture, but several sites, such as Flickr, Fotolog, and Tumblr, were actively followed by graffiti writers. Later, during the interviews conducted in 2018–2019, it was evident that Instagram had jumped into the fray, as it spontaneously became a common topic in all interviews and was presented as a dominant medium for circulating graffiti pictures. It was also on all these platforms that graffiti writers could randomly spot their own works online:

I don’t cry over spotting my pieces on Instagram. I make them in public space. I often hope that they won’t be there [online], but I’m not worried about it. I should cover them up or make them in hidden places if I don’t want them to be seen. It’s another thing if I give my picture to a friend and he publishes it without my permission. (Aleksi, 2019)

The extract above reflects the online circulation of graffiti images as a by-product of contemporary graffiti writing in public space, independent of the writers’ own publishing patterns. The online sharing of images reduced the exclusivity of a graffiti piece, meaning they generally became less scoopful in printed magazines or graffiti books. But there were also useful effects; a train piece that was not spotted offline and that eventually appeared online could offer valuable documentation for the writer. More-over, following the Instagram accounts of local train-chasing obsessives allowed train writers’ to keep up to date on who painted what and on which train lines, which in turn had an effect on their everyday practices. The constant flow of online information was used to compound a spatialised knowledge of the subcultural field which directly involved one’s own train writing practices. For example, if a train line was considered as having been painted too often on the basis of many online updates within a short period of time, this could indicate that a specific spot had changed in terms of its surveillance and had thus become easy to paint. On the other hand, this could also have been interpreted as the spot having become too busy, which could, in turn, lead to increased surveillance.

The participants’ online interaction is best characterised as a one-way digital process of gathering information on urban spots and on how and where to paint. While observing writers in their homes, I often sat with them in front of computer screens as they were exploring spots by studying several online resources simultaneously. The informants could spend inordinate amounts of time researching different online platforms for graffiti photos from a particular city or a specific train system, and investigating timetables and routes to enter different train lines, tunnels, and yards worldwide. Digital media, in-cluding Google Maps and train spotter websites such as Urbanrail.net, allowed these writers to engage in creative ways to plan trips to other localities for the purpose of painting different subway or train models. This was realised specifically by ‘virtually’ travelling to spots in different cities, such as a specific subway yard, and by interactively exploring several information resources and discovering the routes to enter them:

In a YouTube video, a group of graffiti writers have just climbed down a cement fence. They are entering the subway yard. I watch Tony rewinding the clip again and again. He pushes the pause button second by second. ‘Yes, look at it. It has to be somewhere next to a street, because you can see the streetlights quickly on the right corner’. The scene is blurry, and I have difficulties in recognising any streetlight on the screen. Tony checks the Google Map again and zooms into the subway yard, setting the street view. He is persistent in finding that same cement fence seen in the video clip. ‘It has to be somewhere here…’, he points with the cursor on the screen. ‘I will check it out next summer when I’ll be traveling down there’, Tony says. He then returns to study the city’s subway timetable. (Fieldnote, 2013)

The interplay between different information sources enabled writers to gain a complex spatial understanding of certain geographic locations, despite their own physical location at the time. Thus, people’s images and videos of urban spotting uploaded to online platforms, had created the opportunity for writers to start a form of online spotting, and it is this digital exploration of spots that characterises the digital realm as a resource for writers’ subcultural play, a ‘circle back on their sources’, as Ferrell and Weide noted about mediated spots (2010: 59). In fact, online spotting very much simulates exploring and mastering spots in situ. A diverse set of media can thus be used to construct a cartography of graffiti spots – a mental map of what, where and when by ‘following’.

Protecting Urban Spots

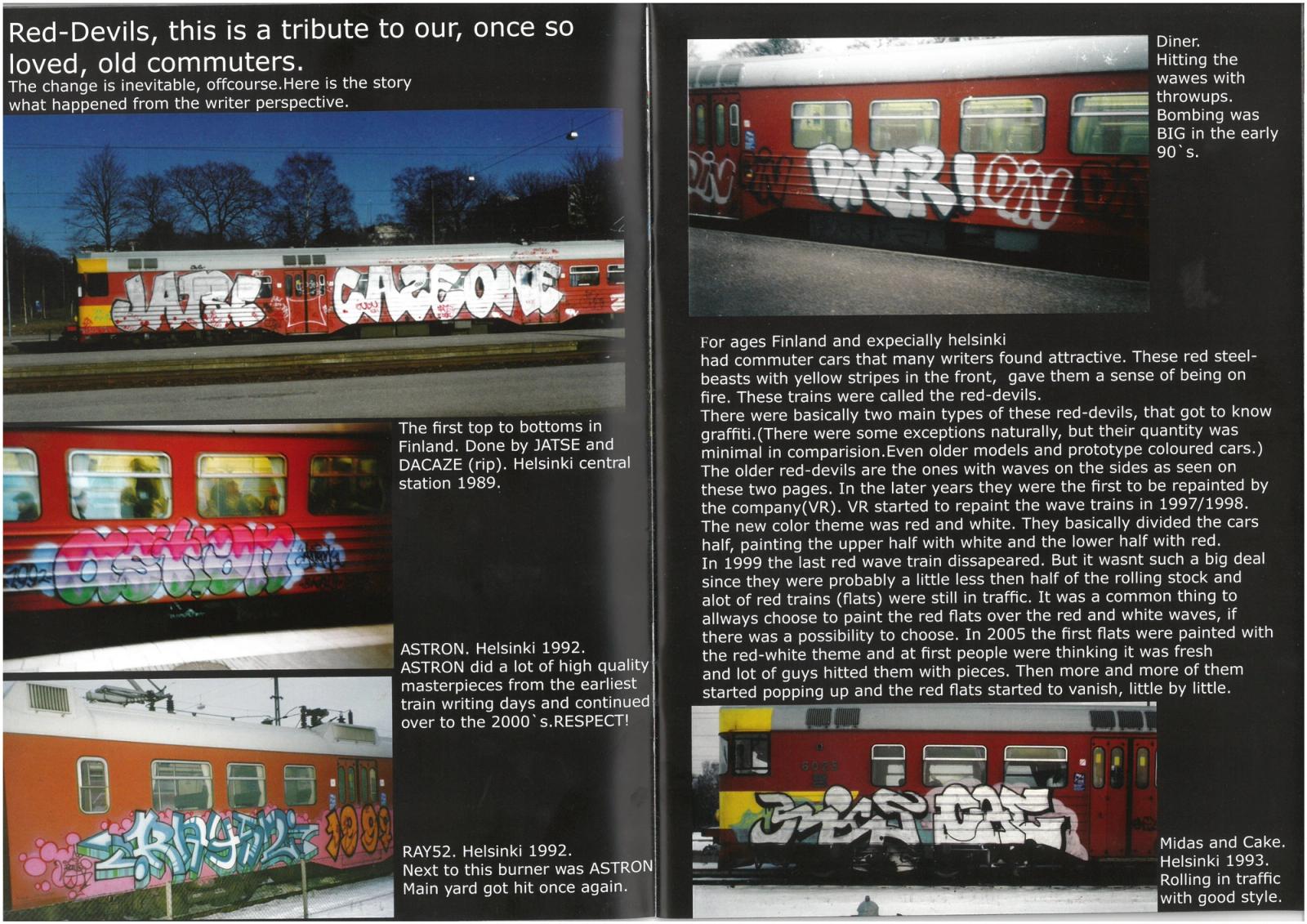

Within graffiti subculture, ‘collecting systems’ comes down to spray painting as many different train models as possible and could be understood as an extended level of moving up from ‘all cities’ to ‘all nations’. As the graffiti subculture has developed into a transnational movement, cities have come to represent certain tastes with their distinct train models. Graffiti writers collect different systems and often appreciate old train models; in terms of prestige, the New York City Subway has earned the status of being the most legendary object to paint, yet some writers enjoy the time-honoured RVR trains existing in Post-Soviet states, while in Finland writers value the old commuter Sm1 train endearingly named the ‘Red-Devil’ (see Figure 4). As cities employ different strategies and policies to combat graffiti, the train system itself is also affected by the policies of local authorities.

Some systems, such as the old RVR trains in Belgrade, are fully covered by graffiti, and writers struggle to find a clean or an appropriate space to cover while avoiding conflicts with other graffiti writers. Other train systems are rigidly controlled and get cleaned continuously, like the Stockholm subway (Karlander, 2018). Moreover, different policies apply to different train systems, which, in turn, differ from each other in terms of volume and physical appearance, and therefore present different opportunities for writing surfaces in the ecology of the city’s spots.

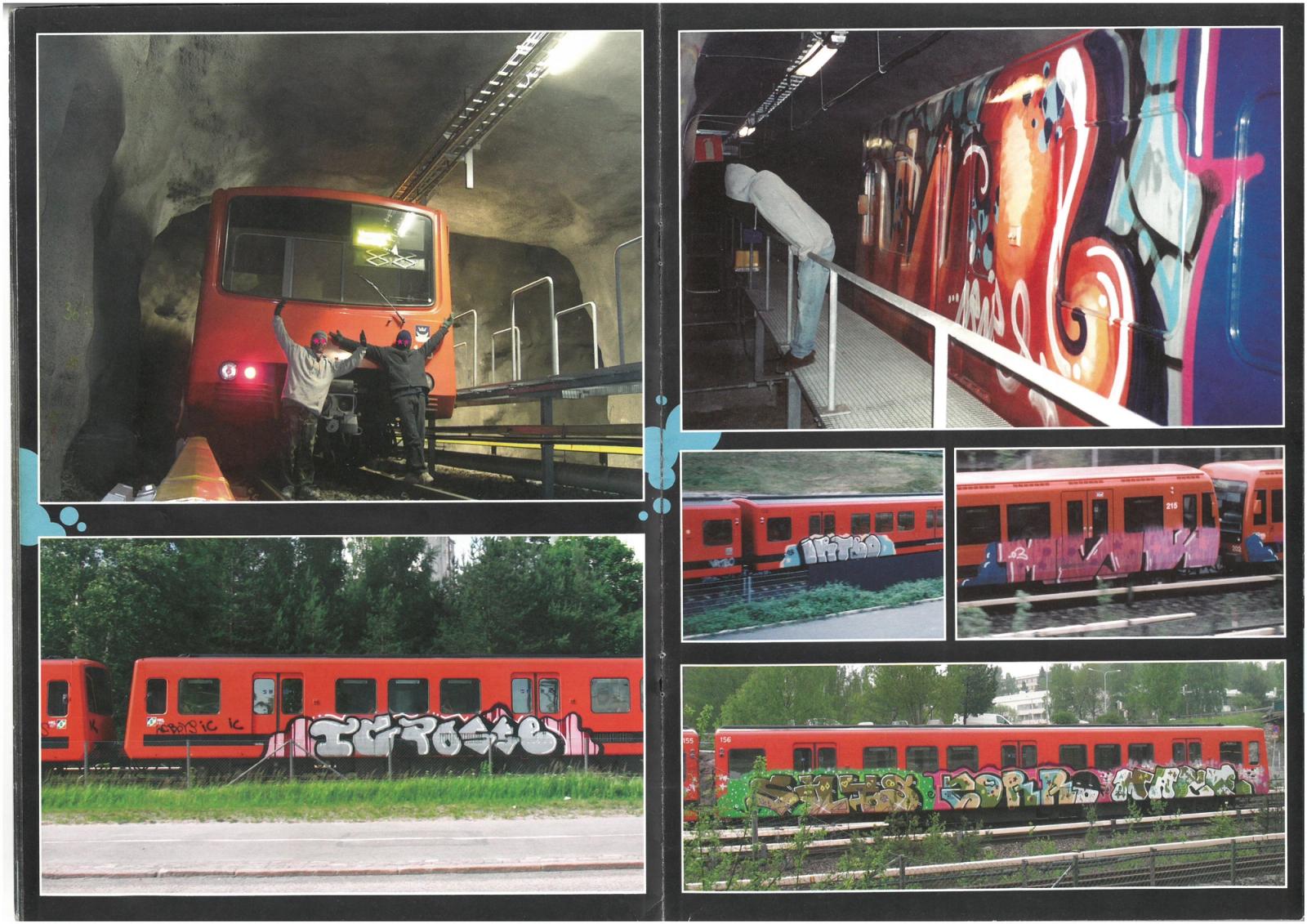

The local writers often described Helsinki as a difficult city to paint in, referring on the one hand to its zero tolerance policy, and other other to the compact train system which offers limited spots to paint on. The Helsinki metro, sometimes nicknamed the ‘carrot’ due to its orange colour, was built in 1982 and has only one line consisting of 25 stations. The Helsinki metro has one metro yard and only a few layups, making it the smallest metro system in the Nordic capitals. It turned into a desired transnational subcultural target for its limited accessibility, for being part of a graffiti-controlled city, and also for being the one closest to the North Pole:

It’s really a wanted train [Helsinki metro]. And it does have a bad reputation […] But maybe a bit too hard a reputation. I mean you can always do a back-jump. It’s doable. But, to do a really good piece, that’s really hard to do. That’s respected and wanted. I think one of the most wanted trains in Europe, maybe. (Risto, 2018)

The ‘backjump’ method originated in the early 1990s in Scandinavia and is a subgenre of train writing particularly used in well-guarded train systems (Kimwall, 2014: 194). In a backjump, the writer quickly completes a piece on the train in service during a prolonged stop, such as at a terminal station (Karlander, 2018). A backjump spot at a terminal station is fairly accessible compared to sealed off metro depots, and a proficient writer is able to complete a backjump within minutes. Compared to terminal stations inside tunnels, outside stations are preferable from a writer’s point of view, as they are less secure and usually only necessitate a jump over a fence next to a track to reach the train. Yet, in Helsinki, there is only one outside terminal station. Thus, to paint sophisticated and complex graffiti pieces requires not only more time, but also a lot of information on routes to enter less visible spots, and on alarms and motion detectors possibly situated in these locations.

Exploring mediated spots online revealed how ‘other’ graffiti writers, travellers from abroad, non-locals, and graffiti tourists examined the train models and spots in Helsinki. Finnish graffiti magazines sporadically present graffiti on the Helsinki metro, but as it is different from the local commuter trains, the metro appears to be a rare object among the local writers: ‘If the commuter train is hit ten times every week, the metro is painted maybe ten times in a year’. Nevertheless, the first volume of Anti-Social magazine presented a section of graffiti painted subway carriages. The spread depicted in Figure 5 was in no need of words as the images are sufficiently potent; in one of the photos, two writers pose in front of a carriage in a tunnel with their arms triumphantly up in the air. In another magazine, Boiling Point (Vol. 2, 2012), the editor’s note describes just how challenging it is for a writer to have a go at the metro in the Finnish capital:

The Helsinki subway is one of the hardest trains to paint in the world. The things that make it so hard, are the size of the system and of course the city’s graffiti policy, zero tolerance indeed!

Finnish graffiti movies are rare, but a few such movies published by non-locals presenting sequences of Helsinki metro graffiti can be found online. In one of them, a movie called Hamaz II, a scene (16:30) presents the Helsinki metro ‘as a system that seems to take the word impossible as its model’. Right thereafter though, the voice-over says that ‘…once you are here, and see it with your own eyes, you know that there is a way to make the impossible possible’. The scene continues with a group of graffiti writers quickly painting a backjump on the Helsinki metro. Graffiti videos published online of the Helsinki metro were seldomly respected by the informants, who were highly critical of how the footage revealed too much information on the local spots. It was precisely because of the limited opportunities that the train writers seemed to be keen on protecting ‘their’ spots of train writing:

Of course, you hope that others don’t do your spots, but if they find their way in there on their own, you can’t complain. The main reason [for not publishing movies] that I’m stressing about, is that you show off about how you do things. (Aleksi, 2019)

By ‘showing off’, media are understood to expedite the identification of the locations of specific spots, arousing the curiosity of other writers about these spots. The fear of Helsinki becoming a popular city for graffiti writers around the globe as a result of the increase in online publishing, provoked hostile attitudes among some of the informants. Moreover, the anxiety about the city becoming too exposed was reinforced by the experiences from other popular graffiti cities:

We can’t have the [graffiti] tourist seasons like they have in Berlin and Copenhagen. We would not be able to paint then. [If we had the same situation we’ve seen] some summers in Berlin, it would be impossible for us to paint the trains here (Kari, 2018).

Therefore, too much media attention, publicity, and visibility seemed threatening for a subcultural landscape with limited resources for train writing. Aleksi proposes that local writers and authorities thus share a common rationale concerning the visibility of train graffiti in Helsinki:

I think VR and HSL want to keep up their image of having a top security system, so it’s sheepish if [graffiti] stuff is seen. Like, when the Germans entered the [metro] hangar, they did a big thing about it. Again, it’s like writers and authorities have the same agenda in keeping tourists outside. We have the same motivation. I don’t think we can stop them [tourists], but it doesn’t help us if people keep shooting their videos.

Aleksi refers to an event in 2011 when a group of graffiti writers entered the metro yard in Helsinki and painted four graffiti pieces on one of the carriages. The event was filmed and later published as a scene in an online graffiti movie. The video included several scenes of train painting missions in different European cities, and provided a peek into the transnational subcultural game of train writing, ‘collecting systems’ in jargon. The graffiti video became national news in 2013, when the police stated that four young men had travelled to Helsinki with the specific intention to paint the metro and that they had subsequently released a scene of the event in a graffiti movie.

Two years after the graffiti writers left the city, an international warrant was issued to arrest all four of them. Eventually they were each prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to a six months’ probation and a €10.000 fine by a Helsinki court in 2014. Among the local writers, these ‘tourists’ were labelled as amateurs as they had touted their novice eagerness to gain publicity for a one-time ‘hit’ on the Helsinki metro. For the locals, the case proved that publishing online is not without consequences, as it led the local police force to track down the offenders.

In this case, it was not only a fight against the controlling authorities, but also against ‘outsiders’ and those who are defined, as in the statements by Kari and Aleksi above, as ‘tourists’ in order to maintain a subcultural exclusiveness among the local train writers. Disputes in the graffiti community are often related to one’s honour being at stake, usually as a result of a writer’s tag in public space being ‘crossed out’ (Macdonald, 2002: 211). Likewise, others have noted that spots claimed by locals may trigger conflict if outsiders paint in these spaces without permission (Ferrell & Weide, 2010: 51). With regard to the fluid realm of urban and mediated spots, and with a diverse set of contesting subcultural media players, there is a desire to understand the emerging and active use of media by those who want to stand out in the subcultural field. Here, the virtual reinforces new territories of subcultural play, altering enclaves of ‘locals’ and those who attempt to be in control of certain spaces in mediated and transurban subcultures.

Conclusion

Spatiality, or spots, are resources for subcultural play and, as such, are fought over, controlled, and used in the game of name writing, which unfolds on trains among other places. Media can be used to navigate the city’s subcultural landscape and they therefore serve as a learning tool in knowing the city as your own, creating a site for spotting and belonging to subcultural play. Austin refers to this cognition as a body of spatialised local knowledge that is reproduced in the peer culture ‘since the necessary [knowledge] for writing is not available elsewhere’ (Austin, 2001: 65). Clearly, the expansion of online information resources challenges the notion of ‘local’, much in the same way that it callenges the boundaries that mark acceptable doings within the subculture, as the media actors are not merely city residents or certain groups denoted as subculturally exclusive, but also people who happen to pass by and become interested in the city as a site for subcultural play.

This article has explored a group of male graffiti writers’ subcultural media practices through the methodology of spotting trains. At times, these graffiti writers were hostile towards outsiders on account of certain media practices and in the context of maintaining dominance in the city’s train writing subculture. Mostly, they preferred their pieces to appear in local offline publications and graffiti magazines that exclusively involve the local scene and that are printed in small numbers. These publications distinguish themselves from the much more widely followed online media channels of what the graffiti writers called ‘tourists’. The train writers in the Helsinki community would painstakingly gather information online, but would not take part in the process of uploading content and sharing their creativity online. Subcultural micromedia, such as specific Instagram accounts and YouTube videos, were preferably used to identify locations, ‘mediated spots’, and to gain temporal-spatial knowledge of spots in different train systems.

One may ask if the subcultural media practices of these local graffiti writers are specific to this group. This would require a larger comparative look at the ecology of spots in different cities and necessitate taking into account subcultural media practices in relation to social class, gender, ethnicity, and age. However, some general thoughts can be offered about the studied case, as the group of train writers consisted of white males employed in male-dominated, but precarious sectors of society. After years of graffiti writing, they had clearly developed a deep subcultural identity and they were obviously committed to play a part in the city’s subcultural scene. Moreover, their experience with zero tolerance policies and the limited number of spots in the city, along with the criminal convictions and the ensuing economic consequences some had faced, marginalised their position in the city, even if this experience gained them respect in the local subcultural scene. Against this background, developing an artistic career on the basis of subcultural fame was challenging. The idea of a commercial graffiti career developed out of a subcultural pastime would in any case have been problematic in the sense that it implies by and large leaving behind what is ‘underground’ and working towards a taken for granted middle-class lifestyle ‘ordinary’ people strive for.

The photos of spotted trains proved to be a significant subcultural source for these graffiti writers, and surely, they would have been able to travel far with the recognition and fame earned in the form of these photos. Yet, they were eager to control the circulation of these photos for the fear of losing their limited spots to ‘outsiders’. Further-more, seeking respect and prestige in the local community was not based on simple visibility, ‘fame’, and a flourishing circulation of graffiti painted trains on all kinds of media channels. Rather, these writers built their subcultural judgement on prohibited and acceptable doings coupled with the limited and controlled spatiality for train writing in the city. This indicates that solutions in a distinct subcultural context are not only reduced to values of a global subculture, but work interactively with the moral codes implied in locally distinct subcultures. Whether the media practices were significant for their social background calls for further studies, and a more profound sociological analysis is thus encouraged in order to engage graffiti and street art research with questions of structural inequalities.

This article captured the theoretical intersection of cultural criminology and subcultural theory, and has provided a perspective on how urban policies, such as zero tolerance, have a dynamic influence in the shaping of boundaries and meanings of difference in subcultural media practices. In subcultural theory, exploring media practices has been crucial in defining both the subcultural difference and the social logic of subcultural capital, and the latter’s relevance in illustrating a mainstream represented by the mass media (Thornton, 1995). Within graffiti subculture, fame as a form of visibility has largely been understood as the subculture’s own form of subcultural capital. Yet the narrow perspective employed on the graffiti career and the alignment on the transferability of fame as a form of subcultural capital into an economic one have, in some aspects, resulted in overlooking the complexities of urban space and the ways in which it distributes power and affects cultural notions around the able-bodied in local specificities. As graffiti subculture has developed into a global game of writing, taking part in it is most likely to be the privilege of white, middle-class youth who have the means to travel and are least dependent on spots in a single city.

Malin Fransberg is a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Social Sciences at Tampere University. She is a sociologist and specialises in subcultural theories, gender, and cultural criminology. Fransberg is currently finalising her doctoral thesis on the Helsinki based graffiti sub-culture, in which she analyses the social consequences of the city’s zero tolerance policy on graffiti and its burden on the subculture’s gender performativities.

- 1

All fieldnotes and quotes were anonymised and translated from original scripts into English by the author, except the English quotes in Finnish graffiti magazines – these were kept in their authentic forms with their typographical errors.

- 2

- 3

Theorising zero tolerance is beyond the scope of this article. However, the following note is worth mentioning: there is a specific history of zero tolerance politics against graffiti in the Nordic countries, that, since the 1990s, has been partly lobbied for through public anti-graffiti campaigns in which many of the Nordic train companies were active (see i.e. Kimwall, 2014). The Nordic zero tolerance dictated a principle of complete censorship of both legal and illegal graffiti in public and private spaces.

- 4

A Finnish graffiti magazine, which will not be disclosed here to avoid conflicts inside the community.

- 5

Hamaz II can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Ic3AlYD6EE&t=996s.

- 6

‘Perpetrators of the graffiti attack on Roihupelto are known to the police’ (headline translated into English), Yle News, May 17, 2013. https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-6646878

Austin, J. (2001) Taking the Train: How graffiti art became an urban crisis in New York City. New York: Columbia University Press.

Blackman, S. & Kempson, M. (eds.) (2016) The Subcultural Imagination – Theory, Research and Reflexivity in Contemporary Youth Cultures. New York: Routledge.

Bloch, S. (2019) Going All City. Struggle and survival in LA’s graffiti subculture. Chicago: University Press.

Castleman, C. (1984) Getting Up: Subway Graffiti in New York. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ferrell, J. (1999) ‘Cultural Criminology’. Annual Review of Sociology, 25: 395–418.

Ferrell, J. & Hamm, M. (eds) (1998) Ethnography at the Edge: Crime, Deviance and Field Research. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Ferrell, J. & Wiede, R. (2010) ‘Spot Theory’. City, 14(1–2): 48–62.

Hannerz, E. (2017) ‘’Bodies, doings, and gendered ideals in Swedish graffiti’. Sociologisk Forskning, 54(4): 373–376.

Hannerz, E. (2016) ‘Redefining the subcultural: the sub and the cultural’. Educare, 2: 50–74.

Hayward, K. (2009) Opening the lens – Cultural criminology and the image, in: Hayward, K. & Presdee, M. eds. (2009) Framing Crime – Cultural Criminology and the Image. New York: Routledge.

Hayward, K. (2012) ‘Five spaces of cultural criminology’. British Journal of Criminology, 52: 441–462.

Jensen, S.Q. (2018) ‘Towards a neo-Birmingham conception of subculture? History, Challenges, and future potentials’. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(4): 405–421.

Joseph, L. (2008) ‘Finding Space Beyond Variables: An Analytical Review of Urban Space and Social Inequalities’. Spaces for Differences: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 1(2): 29–50.

Karlander, D. (2018) ‘Backjumps: writing, watching, erasing train graffiti’. Social Semiotics, 28(2): 41–59.

Kimwall, J. (2014) The G-word: Virtuosity and Violation, Negotiating and Transforming Graffiti. Årsta: Dokument Press.

Lachman, R. (1988) ‘Graffiti as Career and Ideology’. The American Journal of Sociology, 94(2): 229–250.

Macdonald, N. (2002) The Graffiti Subculture: Youth, Masculinity and Identity in London and New York. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

MacDowall, D. (2019) InstaFame: Graffiti and Street Art in the Instagram Era. Bristol: Intellect.

Snyder, G. (2009) Graffiti lives! Beyond the Tag in New York’s Urban Underground. New York: University Press.

Snyder, G. (2006) ‘Graffiti media and the perpetuation of an illegal subculture’. Crime Media Culture, 2(1): 93–101.

Stewart, J. (2009) Graffiti Kings: New York City Mass Transit Art of the 1970s. New York: Melcher Media/Abrams.

Thornton, S. (1995) Club Cultures – Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Young, A. (2014) ‘Cities in the City: Street Art, Enchantment, and the Urban Commons’. Law & Literature, 22(2): 145–161.