This paper positions urban art as a response to the social, political and physical landscapes in which it is created. In Christchurch, New Zealand, a city with a conservative, colonial identity, urban art interventions served to respond to the prevailing environment in the wake of the devastating cluster of earthquakes that struck the city in 2010 and 2011. The earthquakes, themselves the primary vandals, provide a distinct context for uncommissioned performances of urban art – rather than fractures of order, they served as activations, as acts of beautification, transformation, and communication – from gestures of care to critiques of the recovery process.

Introduction

Urban art is a response. In their increasingly diverse incarnations, graffiti and street art remain reactions to the social, political, economic, or physical manoeuvres that surround us and impact us individually and collectively. It is no surprise that scholars and historians have connected the flourishing of graffiti and street art with the urban conditions in which they have emerged, perhaps most explicitly in the state of New York as graffiti writing exploded on the city’s subway trains (Castleman, 1982; Silver & Chalfant, 1984; Austin, 2001; Stewart, 2009; Chalfant & Jenkins, 2014). As Jeffrey Deitch has suggested, graffiti’s emergence occurred within a period of political and economic problems, rather than prosperity and expansion (Deitch with Gastman & Rose, 2011: 10–15). With the city bankrupt and feeling a sense of abandonment, the pervasive environment was an apt setting for the appearance of graffiti writing. Indeed, Carlo McCormick has even ruminated that the bold and brash graffiti writing might be viewed as a ‘reflexive beautification’ of New York’s bleak physical infrastructure (McCormick in Deitch with Gastman & Rose, 2011: 19–25).

In Christchurch, the largest city in New Zealand’s South Island, the earthquakes that struck the city in 2010 and 2011 have provided a distinct lens through which to consider urban art as a response. The earthquakes served as the primary vandals of the city and the urban art that followed, as secondary acts that responded to the physical, social, and political impacts, both in the immediate wake of the quakes and throughout the protracted and complicated recovery process. With the damage to and loss of homes, work places and community spaces, either by nature’s force or by a drawn-out political process, the altered places and spaces left behind, as well as the abundant and often frustrating presence of post-quake symbols such as hurricane fencing and ordinance signs, provided a fascinating landscape for artists to explore. Taking up numerous guises, a reflection of contemporary urban art’s global evolution, examples of graffiti, street art, and what might be considered independent public art (a term adapted from Rafael Schacter, who in turn acknowledges a debt to cultural theorist Javier Abarca (Schacter, 2013: 9)), alongside other institutional public art projects, appeared throughout the complex and changing post-disaster terrain, providing acts of activation, transformation, exploration, population, and critique. Uncommissioned urban art avoids the organisational and logistical difficulties apparent in the production of public art, requirements often exacerbated by the post-disaster setting, providing more direct and immediate interventions (Seno et al, 2010). While the more official additions of large-scale murals and cultural events have garnered celebratory headlines, the practices of guerrilla urban artists have highlighted the complicated nature of a ruptured landscape, where the earthquakes can be considered the more violent antagonists.

Urban Art and Natural Disasters: Creating Context

The Christchurch earthquakes have provided an understandably rich source of discussion and analysis, from scientific and seismic research and social issues, including the impact on animals (Sessions & Bullock, 2013; Potts & Gadenne, 2014), to celebrations of the city’s lost and damaged architecture (Ansley, 2011; Parr, 2015), photographic surveys of the post-quake city (Howey, 2015), the comprehensive documentation of varied post-quake projects (Bennett, Boidi & Boles, eds., 2012), and more analytical discussion of the complex process of rebuilding a city (Bennett, Johnson, Dann, & Reynolds, eds., 2013). The presence and roles of art have been part of these discussions, including urban art (Bennett, Boidi & Boles, eds., 2012; Macfie in Bennett, Dann, Johnson & Reynolds, eds., 2014). However, in most cases it has lacked in-depth analysis and a contextualisation within the narratives and histories of graffiti and street art as developed artistic cultures.

Research for this article was primarily conducted through first-hand experience within the post-quake city, reflecting a real-world reading of the various interventions considered. However, it is also important to acknowledge the writing that has influenced the conceptualisation of this work. Twenty-five years ago, graffiti and street art may not have been considered as a meaningful part of a post-disaster discourse. Indeed, locally, the Napier earthquake of 1931 unsurprisingly revealed little research and documentation of the reimagination of the post-disaster landscape by intrepid artists. However, by the later Twentieth Century and first decades of the new millennium, the ubiquity of urban art across the globe has ensured it is a fitting field of enquiry, and the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake in San Francisco, Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, and the Haitian earthquake of 2010 provided useful, if inconsistent, insights into the performances of urban art in these varied post-disaster landscapes.

While authors have often discussed graffiti and street art within generic urban frameworks (Lewisohn, 2008; Waclawek, 2011), others have located their investigations within more specific settings of time and place. Despite graffiti and street art’s global commonalities, such localised studies have revealed the unique variants evident in specific environments, from the amalgamation with local cultural histories, to sociopolitical and economic influences.

By locating these studies in specific locations and time periods, authors have been able to illuminate the unique nuances of various settings, at times identifying historical, physical, and cultural influences (Manco, Lost Art & Neelon, 2005; Gastman & Teri, 2007; O'Donnell, 2007; Grvy, 2008; Gröndahl, 2009; Parry, 2010; Smallman & Nyman, 2011, Munro, 2012). While such works explore the cumulative physical, technological, social, cultural, and economic elements that have facilitated distinct regional qualities and histories, they often focus on the more insular narratives of these cultures and artists, rather than the influence of specific sociohistorical events. While some have connected the appearance of urban art to events such as the War on Terror (Tapies & Mathieson, 2007), an investigation of urban art’s roles in post-quake Christchurch affords the consideration of a broader spectrum of performance. According to cultural geographer Luke Dickens, as urban manifestations of place, graffiti, and street art engage with issues of identity politics, territoriality, urban decline, transgression, resistance of authority, and suggestions of possible ways of reading, writing, and reimagining cities (Dickens, 2008). Within the context of a natural disaster in an urban setting and the necessary task of recovery, urban art reveals a range of performances and potential readings, both specific and universal.

Urban Art in a Colonial City

Ōtautahi Christchurch has historically lacked a strong sense of public space cultures, often stuck with a conservative reputation sprung from its colonial transplant identity, and evident in its neo-Gothic architecture and statues of colonial forebears (Rice, GW. 2008). Yet Christchurch’s post-quake creative landscape has been strongly entwined with the city’s streets and public spaces, including the previously peripheral, marginalised, and often vilified presence of graffiti and street art. While reaching new levels of prominence, these forms were also imbued with various meanings over the drawn-out recovery, forming an evolving and interesting aspect of the post-disaster environment. Vera May, writing about Australian artist Shaun Gladwell’s 2013 work Inflected Forms, produced for the Christchurch public art event SCAPE, noted that: ‘It can be argued that the first to reclaim a city after experiences of radical material transformation are neither urban planners, bureaucrats or politicians (those officially tasked to make decisions around urban revival), but rather those who actively write the city beyond the confines of grids, paths, and signs of urban decorum and regulation’ (May in French, ed., 2013: 53). While May was referring to the skateboarders that influenced Gladwell’s sculptures, graffiti and street artists can also be viewed in this regard, exploring the various spaces of the post-quake city and adorning the spaces in ways that suggest renegotiation. In the immediate and prolonged wake of the quakes, urban artists, uninvited in the normal sense, were compelled to explore and transform the city in more prominent ways than the pre-quake city had afforded. In doing so, their acts of guerrilla urbanism served as reactivations and reimaginations of place, and considerations of the earthquakes’ prolonged impact, distinct from the structured, planned, and organised rebuild process, inviting different responses and providing alternative readings of the city, it’s histories, and potential future (Hou, 2010).

There is little formally recorded and documented history of Christchurch’s pre-quake graffiti or street art cultures; stored instead in personal photo collections or recounted verbally between artists. In addition, the city has often been overlooked in favour of Auckland and Wellington (New Zealand’s other significant urban centres, where graffiti emerged earlier than Christchurch), even as documentation and discussion of the New Zealand urban art scenes have grown in the new millennium (O’Donnell, 2007; Munro, 2012; Merkins & Sheridan, 2012; Liew, 2013/2014). There had long been graffiti in Christchurch in the form of parietal writing, prominent Christchurch writer Lurq recounted the early Christchurch graffiti scene as ‘…really just political slogans and gang emblems and a giant Ghostbusters symbol’ (O’Donnell, 2007: 111). By the early to mid-nineties, tags and outlines, representative of signature-based hip hop graffiti, emerged, most commonly occurring in the peripheral spaces of train tracks and alleyways. While a small community, street art, or post-graffiti, was less prominent in Christchurch, with a small selection of stencils, paste-ups, stickers, and other forms of urban painting appearing in the new millennium, often in more populated spaces than graffiti. Although there was some sense of social overlap between graffiti and street artists, existing distinctions between the two remained and street artists shared a less defined sense of community. By the time the earthquakes struck in 2010, urban art, while an entrenched presence with its own sense of history, was not considered a defining visual element of the Christchurch’s physical spaces or creative identity.

The Christchurch Earthquakes: The Primary Vandals

For many Christchurch residents the earthquakes provide a demarcation, rendering the city definitively ’before’ and ’after’. For those forcefully stirred from their sleep early on the morning of September 4, 2010, the violent shaking was an abrupt, unexpected and confusing, almost surreal experience. Striking at 4:35am and measuring magnitude 7.1, the September quake lasted less than one minute, but it would form the opening chapter of a much larger narrative. Importantly, primarily due to the early morning timing, no-one perished as a direct result of the quake, and, as the editors of Once in a Lifetime acknowledged, ‘it felt like a bullet had been dodged’ (Bennett, Dann, Johnson & Reynolds, eds., 2014: 18). Over the following days, weeks, and months, aftershocks and a stream of news reports began to create a greater sense of the realities of life in an active quake zone. Visible signs of physical damage were evident across the city, from cracked suburban homes, to the crumbled brick work of inner-city buildings. While there was a lingering psychological impact in jittery responses to aftershocks, within a week many infrastructural services had returned, allowing some level of normality to resume, suggesting that the city was now better prepared for future quakes (The Press, 2010).

On February 22, 2011, that sense of relative fortune was eroded, and the notion of preparedness tested, in another seismic burst. At 12:51pm, a 6.3 magnitude quake shook the city, from a shallow depth under the nearby Port Hills. The February quake resulted in even more severe damage to the already affected natural surroundings and built environment, from the subterranean infrastructure to the high-rise buildings that were left notably askew. This time lives were lost. Deaths occurred at points across the city, with a final toll of one hundred and eighty-five people. One hundred and sixty-nine of those perished within the central city. Confidence in the built environment, already shaken, was eroded even further.

The city was transformed, and ultimately would undergo a lengthy period of demolition and slow rebuilding. Spaces and places people knew intimately, from the suburbs to the central city, were now either vanished or severely altered. In the suburbs, the residential red zone sprawled eastward from the central city, whole neighbourhoods and thousands of houses affected, in many places returned to swathes of grasslands (Gates, in Gorman, ed., 2012: 45–61). Following land damage in September, February proved a death knell, houses were vacated, most demolished, some lifted and transported to new, distant settings, leaving only outlines of past occupancy (Figure 1. An abandoned house in the suburban red zone, Bexley, Christchurch, 2012. Photograph ©Reuben Woods).

While the impact in the suburbs, the dominant residential areas of the city, was significant, the central city perhaps became the most discussed site of the quakes’ ferocious legacy. A tightly defined gridded network of streets and squares, the inner city was rendered almost unrecognisable. George Parker and Barnaby Bennett asserted that the scale of change rendered post-quake central Christchurch ‘deeply disorientating’ (Bennett, Boidi & Boles, eds., 2012: 4). Accompanying the damaged architecture and newly vacant lots left behind by demolition, the central city was framed by a mutating cordon, abundant road cones and shipping containers, and unavoidable ordinance signs. The inner city became difficult to navigate, not only due to the one-way passages and no-entry zones, but also because the familiar markers had disappeared. Parker and Bennett ruminated that if you are, or were, familiar with the city, you may recognise the street names and intersections, but the places are completely changed. You stand there, staring, struggling desperately to remember, struggling to articulate meaning out of the uncanny familiarity (Bennett, Boidi & Boles, eds., 2012: 4) (Figure 2. Damaged central city building, Christchurch, 2013. Photograph ©Reuben Woods).

Furthermore, the process of change, in the suburbs and inner city, was both immediate and prolonged, creating various incarnations of the city, almost day by day. In his 2014 essay Desire for the gap, Ryan Reynolds acknowledged that defining the present state was a complex task, and notably so in the urban centre:

It is a post city, the remains of the complicated, contradictory, post-colonial place it once was, with a centre that is 70 per cent destroyed and sparsely populated. It is also, now, a pre city, with three years’ worth of plans, consultation, ideas, and designs that exist mainly as a massive set of aspirations yet to be enacted. (Reynolds in Bennett, Dann, Johnson & Reynolds, eds., 2014: 167–176)

This transitional setting required constant reconciliation, loaded with suggestions of the past, immediate points of interest, and almost unlimited potential, not only for shiny new buildings but also for smaller individual expressions that attempt to respond to the quakes’ impact. Once largely peripheral, urban art became a visible addition to this terrain, responding to the surroundings both explicitly and inherently. In doing so, these acts of vandalism were lessened in comparison to the destructive impact of the quakes and the complicated issues of the recovery, often serving as eloquent reflections of the experience of the post-disaster city. While these guerrilla creations dissipated the benefits of scale, protection and exposure afforded sanctioned projects, the subversive quality of unpermissioned action also ensured these examples could be read in a variety of ways not available to commissioned counterparts. As often smaller and more mysterious, these interventions were intimate and open-ended, and when surrounded by signs of destruction and bureaucracy, they could be considered an alternative part of the city’s rebuild.

Secondary Vandals in the Post-Quake Landscape: Healing, Reflections, Population, Exploration, and Critique

Across the city, guerrilla interventions, ignoring explicit permission or eschewing commission, previously viewed by some as an annoying nuisance or aggressive disruption, performed a multitude of roles, drawing on global performative traits in response to the specific setting. Many artists bypassed the need for permission to make more pressing expressions. In the post-quake landscape, the concept of permission was less coherent, normal channels of enquiry were ruptured, and altered spaces appeared less controlled. The addition of paint, paper, or sculptural elements to someone else’s broken building, a stretch of hurricane fencing, or a vacant lot, paled in comparison to the violent vandalism of the quakes and the frustration of the recovery process. In doing so, guerrilla urban artists were able to more urgently and more personally reflect the experience of the city than more official projects granted institutional support.

Some artists considered the city as a victim of the earthquakes. This approach was exemplified by the oversized sticking plasters by the duo known as the Band-Aid Bandits, Dr Suits and Jen, that adorned an array of damaged buildings across the central city, personifying the built environment as a body in need of care. The paste-ups were created following a significant aftershock in June 2011 (Dr Suits, 2015) (Figure 3. Band-Aid by The Band-Aid Bandits, central Christchurch, 2011. Photograph ©Reuben Woods).

The large paper plasters, thickly outlined, were an attempt to light-heartedly suggest the overwhelming task of healing faced by the city, despite fears that they might be perceived as insensitive (Dr Suits, 2015). The plasters also provided an offer of comfort in accompanying speech-bubbled declarations such as ‘I’ll kiss it better’, echoing the caring words of a parent to a child.Local art writerJustin Paton noted the symbolic resonance of the gesture of applying a sticking plaster to a child’s injury, more about reassurance than healing, it was both tender and ironic:

On one hand, it feels like an expression of genuine care, with the artist as a kind of urban physician, doctoring to the city’s wounded spaces. But you can also see it as an expression of anxiety and frustration, as if the artist is wondering, in the face of all this damage, what anyone can actually do. Are all our symbolic expressions of care and concern just Band-Aids on an unhealable wound? (Paton in Bulletin, B.167: 19)

The gesture of care represented by the plasters may have been futile, but it did extend a playful, touching sense of humanity and expressed the importance of the recovery of the built environment for the city’s collective well-being.

In Lyttelton, a portside village on the fringe of the city, and the closest residential area to the February quake’s epicentre, another guerrilla artist reflected on the built environment as a victim, buildings as lost members of a community. In May 2011, Delta placed a number of small crosses created from salvaged material from Lyttelton’s numerous demolition sites as memorials on the newly vacant lots along the village’s main street, both a farewell and an act of remembrance. The title of the project, Crux, evoked the cross forms, but also suggested both the important and unresolved nature of the village’s recovery. Each cross was numbered in reference to its location and included an acknowledgement of the date of the February earthquake: 22–2–11, read as the death date of the buildings, echoing the small crosses that dot roadsides memorialising crash victims. Although they lasted only three weeks, the crosses subtly highlighted the now empty spaces along the formerly picturesque main street (Bennett, Boidi & Boles, eds., 2012: 256). The artist described the project as one of remembrance and vision, ‘acknowledging what had been lost in the heart of the township and looking to the future’ (Bennett, Boidi & Boles, eds., 2012: 256). Crux acknowledged the role of the missing buildings in the village’s history and the lives of the Lyttelton community, thus positioning them as a part of the community. The crosses were not grandiose markers of place in the manner of official memorials, but were ephemeral, guerrilla additions. The use of materials salvaged from demolition sites directly connected the crosses to the buildings that had been lost, while also subverting the vandalism of the quakes themselves.

Much like Delta’s crosses, another intervention, this time in the inner city, explored the emotional connection to buildings, while also performing a type of memorialisation. However, rather than serving as an explicit memorial, Mike Hewson’s Homage to Lost Spaces explicitly played on the quakes’ impact on the memory of place. Ruminating on the impact of the city’s fallen buildings and the loss of so many ‘aides memoires’, Christchurch poet Jeffrey Paparoa Holman suggested: ‘…these structures were not only our external memory banks, they were also an internal geography, our shapes, and roadmaps within. We would never be the same without them, but we could be healed if we saluted them and grieved for them’ (Holman, 2012: 50). Hewson’s intervention was a public expression of the personal experience of losing meaningful places. In April 2012, the boarded windows of the vacated neo-Gothic Old Normal School building in Cranmer Square were adorned with enlarged colour photographs of various figures; in a shattered doorway a figure in a hard hat and hi-visibility neon vest was busy talking on a mobile phone, in another window a figure leapt over a desk (Figure 4. Detail from Mike Hewson's Homage to Lost Spaces, central Christchurch, 2012. Photograph ©Reuben Woods).

The images, installed without permission, brought the doomed building to life, as if passers-by could see inside the building and witness new, final activity within its walls. The photographs, from Hewson’s personal collection, documented his time in another building altogether, the Government Life Building situated in Cathedral Square, which at the time of the February quake, was serving as a studio space for a collection of artists. As such the images served as personal memories of a cherished time for the artist, a time abruptly interrupted by the earthquakes that damaged the Government Life Building and led to its eventual demolition. Yet, the lack of knowledge about the (initially) unsigned and unexplained images, and the unexpected nature of their appearance, meant for many they were evocative of some memory of the building itself, despite depicting an entirely different setting. While celebrating a particular and significant aspect of Hewson’s own experience, the placement of the works on the exterior of a building with a sense of civic significance and varied use, both briefly rejuvenated the Old Normal School before its eventual demolition, and also allowed the audience to draw their personal associations with the site through the reactivation.

While these interventions were imbued with relatively tender reflections of the quakes’ impact on the surrounding environment, the traditional performances of graffiti writing offered a more challenging reading of the city’s transformation. Graffiti appeared across the newly vacated areas and buildings. The proliferation of graffiti writing in the suburban red zone signified a returning presence in a forcibly vacated area, replacing departed residents and communities. Families who had nestled into suburban homes over many years were replaced by opportunistic artists, explorers and vandals. Entire houses were overrun with layered collections of hieroglyphic tags and larger scale pieces covering entire walls, often visible from distance and providing an unexpected addition of colour and form. The graffiti writing found in the red zone did not refer to loss, change, or personal attachment in any explicit or even intended content, there were not heart-felt farewells like the messages left by departing families (Figure 5. Graffiti on an abandoned home in the suburban red zone, Christchurch, 2013. Photograph ©Reuben Woods).

While symptomatic of graffiti writers’ use of vacated spaces, by commandeering these once private settings, the overrun homes became symbolic of the fall of these neighbourhoods, houses that were once functional sites of domestic activity turned into blank canvasses to be adorned.

Graffiti writing was also a prominent and obvious sign of presence across the central city, most notably in the larger buildings left vacated by inactive or absent owners. Signature-based graffiti has always been related to the declaration of presence, as Anna Waclawek notes, an assertion of the writer’s identity, and much like the residential red zone, Christchurch’s central city has proven attractive and opportune site for graffiti writers to explore and leave their trace on the exposed walls and empty buildings (Waclawek, 2011: 13). Indeed, it was possible to consider the hieroglyphic graffiti that emerged in the damaged central city as a contrast to the fluorescent markings of the rescue crews on doors and windows of cleared buildings, the last official presence before the central city red zone cordon was erected.The names written across Christchurch’s central city provided an ongoing urban discussion between uninvited and official forces, a conversation that, when juxtaposed with the bustling activity of the rebuild, was distinct from the more isolated experience of the suburban red zone graffiti (Figure 6. Graffiti-covered building in Christchurch's central city, 2017. Photograph ©Reuben Woods).

The combined effects of the cordon, the newly unfamiliar surroundings, the signs of the earthquakes’ ferocity, lingering fear or distrust of the built environment, and the perceived lack of functionality, left the central city sparsely populated in the wake of February 2011. Even as the cordon was reduced and access became greater, an overwhelming sense of emptiness outside of pockets of the revamped urban core remained. While the re-emergence of a commercial presence was a key part of the central city’s recovery and repopulation, a spectrum of arts and cultural events and attractions also played significant roles in enticing people back to the still unsettling surroundings of the central business district. The Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu’s Populate! Programme was positioned as an attempt to return a presence to the central city through the addition of faces and figures, in the form of both new works and reproductions of portraits from the Gallery’s then inaccessible collection. While this ‘population’ of the central city landscape was relatively high profile, graffiti and street art had filled the inner city with figures, names, and messages long before, symbols of an alternative to the official presence of art as a form of reactivation. The expressions, poses, and movements of these various characters engaged the unsuspecting audience, encouraging them to construct the stories and reasons for the appearance of these actors in the broken inner city. Personalities and activities ranged from menacing to mysterious, joyous to disinterested and stone-faced. While some were preoccupied with the surrounding sights, others apparently sought the attention of passers-by. A tiny stencil of a giraffe grazing on a sprouting weed against a concrete wall on St Asaph Street was seemingly oblivious to the surrounding activity (Figure 7. Anonymous giraffe stencil in Christchurch’s central city, 2012. Photograph ©Reuben Woods), while a tiny door crafted from modelling clay (Figure 8. Door crafted from modelling clay, central city, Christchurch, 2015. Photograph ©Reuben Woods), suggesting some fantastical domicile within the urban setting of Cathedral Square, provided examples of the varied occupation of the inner city.The changing appearance of the roving figure of Dr Suits (not a self-portrait but a character sharing the name of the artist), his attire and facial hair varied in each appearance, matching the changing state of the city, has provided a recurring presence, something of a modern day flâneur observing the city (Figure 9. Dr Suits character paste-up, by Dr Suits, central city, Christchurch, 2012. Photograph ©Nathan Ingram).

His sartorial elegance (rarely seen without a bow-tie and dress suit), intended to represent the creative people of Christchurch and their contributions to the recovery, a stark contrast to the city’s unofficial scruffy uniform of fluorescent vests, work boots and hard hats (Dr Suits, 2015).

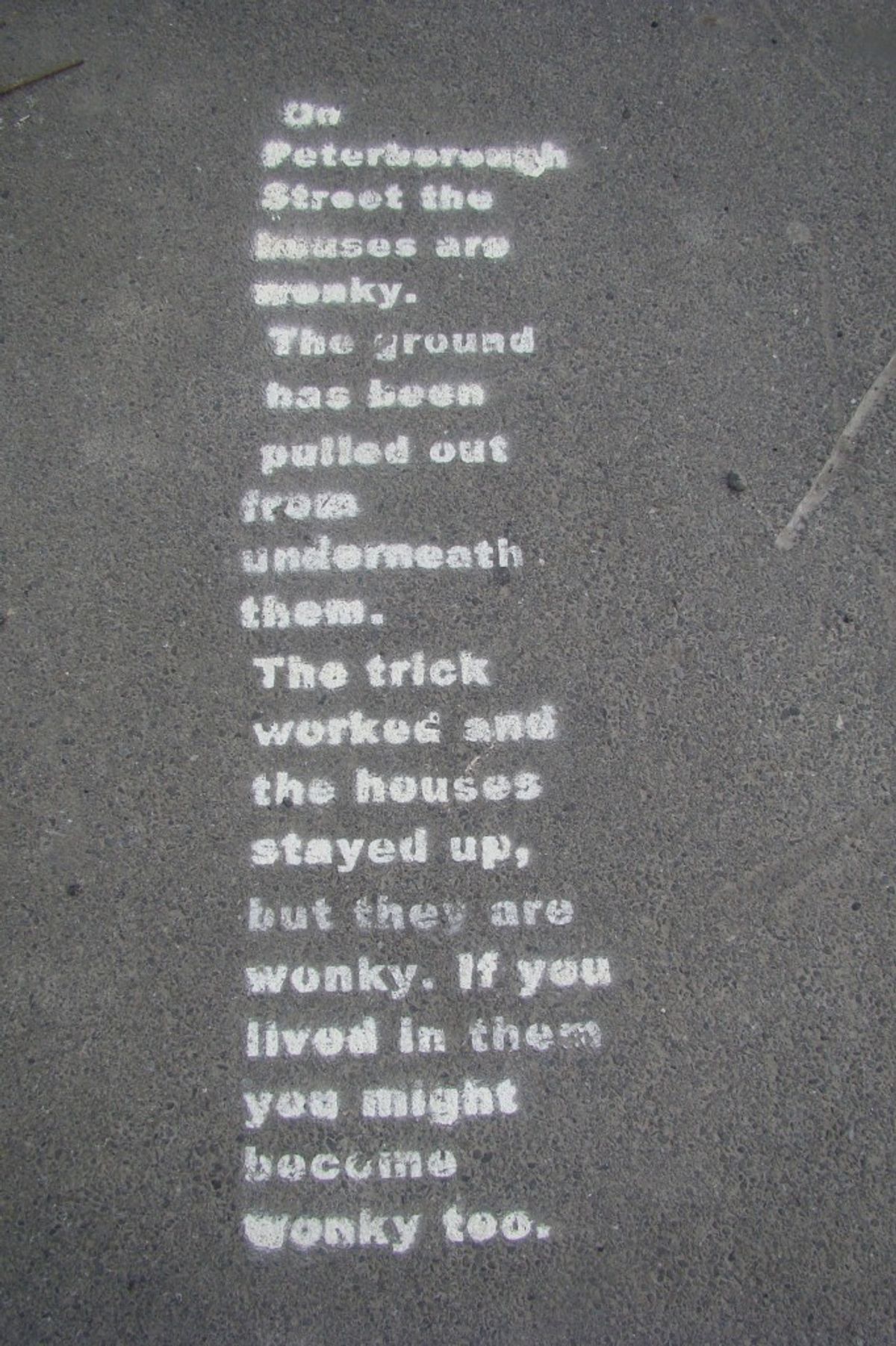

If the hundreds of characters and creatures provided a figurative population of the central city, the suggestion of presence was also evident in the visible text of notes, messages, jokes, and questions plastered across the city. Written phrases, declarations, and observations served as a kind of analogue social media; engaging, surprising, thoughtful, and often humorous conversations that suggested presence in a different manner from the arguably more self-absorbed nature of graffiti, or the official and instructive civic management signs. These text-based interventions created open, unofficial, and informal conversations between the artist/author and the largely unsuspecting audience, who are often engaged in the exchange in an unexpected moment. Contrasting with the official flow of information encountered in urban spaces, these snippets of dialogue did not intend to control, but rather to reflect and combat the feelings of alienation often associated with the congestion of modern cities, a feeling still present in post-quake Christchurch despite the relative emptiness. Such phrases, often in small forms, noticed at closer range than many of the other examples of official communication visible in urban landscapes, presented ruminations that incited a moment of consideration, sometimes posing questions, other times making declarations. On the fringe of the central city, anonymously stencilled in white paint on a buckled footpath, a piece of prose referenced the impact of this change upon the central city and its residents (Figure 10. Anonymous stencil, central city footpath, Christchurch, 2012. Photograph ©Reuben Woods).

The unexpected phrase provided the viewer with a surprising intervention, while connecting the experience of the inner city’s changing physical landscape with a social and psychological impact:

On Peterborough Street the houses are wonky. The ground has been pulled out from underneath them. The trick worked and the houses stayed up, but they are wonky. If you lived in them you might become wonky too.

In a landscape dominated by signs of authority and control, such unexpected conversations provided an alternative to the official flow of information, while also initiating an engagement between people who may never meet.

Intimately tied to the population of the post-quake city was the ability to explore and navigate a newly unfamiliar setting. The trace of the presence that smaller interventions represent also suggested possible paths of movement in a city where previous markers of place had vanished. At times, the exploration of the central city by urban artists was explicitly exemplified by surrogate figures. The running characters attributed to Drypnz, or the incarnations of Dr Suits that appeared throughout the central city’s changing physical make-up, suggested the ability to explore new paths, and due to their own guerrilla appearance, to ignore the directions proscribed by ‘No Entry’ signs and hurricane fencing (Figure 11. Painted character, attributed to Drypnz, central city, Christchurch, 2013. Photograph ©Reuben Woods).

The willingness to explore the more liminal spaces in the post-quake city was also evident in the insides of empty buildings, which, level by level, were turned into secluded galleries by urban artists and graffiti writers. The transformation of these buildings remained largely obscured, save for the paint applied to windows or when the interior was revealed through partial demolition. Despite obvious dangers, such spaces (colloquially referred to as ‘bandos’, short for abandoned) provide sites where artists can spend more time, commandeering floors of buildings. Waclawek asserts that graffiti and street art practices demonstrate a willingness to utilise underused parts of the urban landscape:

No matter how controlled city spaces are, they are also open to subversion. Not every area is monitored, commercialized, depersonalized, or functionalized. Some spaces are unrestricted, unobstructed, exposed, empty, isolated, forgotten, unmanaged, and bleak. Even within the capitalist economy of space, there are gaps or marginal spaces that, while often neglected, are necessary for the conceptualization of the city as a complex arena. (Waclawek, 2011: 114)

In post-quake Christchurch such spaces were abundant and encouraged exploration in the search for freedom amidst the city. The appearance of urban painting in and on buildings that served no other purpose and were essentially on borrowed time, suggested a willingness to explore and reclaim a city that had been altered and recast, making use of spaces that lingered as a direct result of the impact of the quakes.

While these preceding examples highlight the consideration of the city as a site of attachment and functionality, they also inherently suggest a challenge to official order in a highly controlled setting. But the combination of urban art’s resistant and contestant roots and the potential for a disaster to reveal the power relations at play in a city, ensured that urban artists were also explicit in their public critique of the recovery process. Rebecca Solnit has argued that authority will often fear the potential of disasters to undermine their control, that a power struggle can occur, and real social and political change can come (Solnit, 2010: 21). Indeed, the deconstructed city, both physically and ideologically, has allowed the revelation of the underlying social structures and processes evident but often hidden within a city’s existence. George Parker and Barnaby Bennett have noted how the pervasive damage of the post-quake environment has revealed both physical and social aspects: ‘You see things that were once hidden: empty sites and broken foundations, flows of material, networks of support, threads of power’ (Bennett, Boidi, & Boles, eds., 2012: 4). Artists responded by subverting official visual information, from a yield sign reading ‘Wake Up’ in a vacant lot, to a makeshift directional sign where every arrow pointed to a carpark, a commentary on the proliferation of such spaces in the post-quake inner city (Figure 12. Seek's Cardensity installation, central city, Christchurch, 2012. Photograph ©Reuben Woods).

Due to the complicated task of rebuilding, it was unsurprising that political bodies and politicians would become the target of urban artists. In July 2012, street artist Cubey pasted and stuck reproductions of a drawing of Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA) head Roger Sutton, Central City Development Unit (CCDU) director Warwick Isaacs and Earthquake Recovery Minister Gerry Brownlee, three of the most influential men in post-quake Christchurch, across the city (Figure 13. Cubey's Three Wise Men stickers, central city, Christchurch, 2012. Photograph ©Reuben Woods).

The images identified the men as ‘Roga, Waza and Geza’, with Sutton’s mouth covered by a sticking plaster, Isaac’s hearing blocked by construction-site ear muffs, and Brownlee’s vision obscured by a blindfold, rendering the ‘Three Wise Men’ as seeing, hearing, and speaking no truth (Bennett, Boidi & Boles, eds., 2012: 254). Such additions, laced with humour, recognised the politicised environment of the post-quake city and were afforded their voice by their unpermissioned creation, bypassing the censorship of official projects.

Conclusion

Post-earthquake Christchurch has been celebrated for the explosion of urban art, most notably the large-scale murals that have transformed the walls of the recovering cityscape. However, the shattered post-quake landscape was also ripe for the diverse performances of uncommissioned interventions. The violent legacy of the quakes, the primary vandals, and the frustrating process of rebuilding a city, ensured that the intrusion of uninvited urban art was viewed with less derision, instead revealing a number of potential readings not necessarily available to sanctioned projects. Guerrilla artists produced works that acknowledged the quakes’ impact on the built environment and the social relationship with vanished places; works that served to repopulate and renegotiate the altered city; and works that critiqued the power structures at play in the transitional cityscape. In doing so, guerrilla artists revealed the ability of universal tropes of urban art to be applied in the unique setting that post-quake Christchurch provided. Inflicting further damage upon an already complicated landscape, these unpermissioned additions were as much reflections upon another, initial act of vandalism as vandalism themselves.

Dr Reuben Woods is a freelance writer, curator and lecturer, based in Ōtautahi Christchurch, New Zealand. His primary interest is in the diverse practices of urban art and their ability to engage with specific and distinct social and physical landscapes. His PhD, completed at the University of Canterbury in 2016, focused on the varied performances of urban art in the post-disaster landscape of Christchurch following the significant cluster of earthquakes in 2010–2011.

- 1

The diversity of urban art, and indeed the term as an umbrella concept for a wide variety of styles, outcomes, media, and techniques was the focus of the 2016 International Urban Art Conference at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. (Blanché & Hoppe, eds., 2018)

- 2

While the major quakes of September 2010 and February 2011 have been the focus of much coverage, thousands of aftershocks and smaller quakes have rattled the landscape. As such, the effect of the earthquakes on the city’s physical state was drawn out over a lengthy period.

- 3

Abandoned or peripheral spaces have always been attractive to graffiti and street artists. Often such spots, lacking public attention or perceived utilitarian value, become valued locations for urban art communities (RomanyWG, 2008; Workhorse & Pac, 2012). In post-quake Christchurch, the abundance, accessibility, and central locality of such spaces was a fascinating development and created a setting ripe for exploration and decoration, while retaining elements of the seclusion that is attractive to urban artists. In utilising these spaces, urban artists are less concerned with city building in a civic sense, and more so with the creation of spaces for marginal communities to exist.

- 4

Schacter’s use of the term might be most suitably considered as a description of an approach to making art, rather than as a term to define artists.

- 5

It is important to acknowledge that although urban art provides a helpful umbrella term, indeed expansive enough to include practices such as skateboarding and parkour, or free-running, as well, it is important to emphasise the key distinctions that remain between graffiti and street art, not only aesthetically, but also in self-identification by practitioners (a graffiti writer would likely take offense at any description as a street artist) and outwardly in perception. Graffiti remains less socially accepted, while street art is increasingly viewed as a regenerative tool, even in its more rebellious states, often protected while graffiti is actively eradicated (McAuliffe, 2012).

- 6

The 1931 earthquake in the Hawkes Bay area in the North Island was the most significant urban seismic event in New Zealand’s history until the Christchurch quakes, and immediately drew comparison.

- 7

Gröndahl’s work is admittedly concerned with graffiti in a broader, historical sense, but the influence of signature graffiti and street art practices is evident, a reflection of the global migration of these forms and their merging with local traditions.

- 8

Both New Orleans and San Francisco are featured in Gastman and Neelon’s survey, but in both cases the influence of the respective 1989 earthquake in San Francisco and Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans were minimal, a further highlight of the unique nature of this work.

- 9

Ōtautahi is the Maori name for the area on which Christchurch (the major city in the Canterbury province) was founded. The city was intended as an English transplant, with a notable sense of physical order to represent the desired social order of the colony’s founders.

- 10

Contributors to Christchurch’s post-quake landscape ranged from traditional graffiti writers and street artists active pre-quake, to those compelled by this new environment to act with little experience. While some avoided categorisation, at least partially through anonymity, others, such as Cubey or Delta, embraced the term ‘street artist’ as a way to signify an independent practice distinct from public art, despite a lack of historical presence in the city’s urban art scenes. These titles have also evolved as the career trajectories of artists have developed post-quake, for instance Mike Hewson has undertaken a number of commissioned projects in Christchurch and overseas, effectively transitioning into the role of a public artist. Similarly, other figures continue to shift between commissioned projects and illegal works, highlighting the evolving position and possibilities available to urban artists.

- 11

Christchurch graffiti writers were utilising these various techniques too, a reflection of the speedy and less risky tactics offered by stickers and stencils

- 12

Notably, Hewson’s project gained significant attention, and while originally unsigned, he was eventually credited with the interventions, and was provided the opportunity to install a final element with permission and funding. The profile Hewson gained changed the final reading of the work, and his own position. Hewson had no history as a graffiti or street artist, and essentially became a public space artist.

- 13

In some more visible red zone areas, efforts have been made to paint over graffiti. However, the impact of these attempts has often rendered the dilapidated houses as equally despondent as with graffiti.

- 14

In contrast to the performance of graffiti, Australian artist Ian Strange’s Final Act, a project created for the 2013 festival Rise, transformed vacated suburban red zone houses through a combination of rejuvenation and the addition of light. The associative resonance of the emanating light (importantly experienced primarily through the documenting video and photographs rather than in person) provided a very different reading from the pervasive red zone graffiti. (http://ianstrange.com/works/final-act-2013/about/)

Ansley, B. (2011) Christchurch Heritage: A Celebration of Lost Buildings & Streetscapes. Auckland, Random House.

Austin, J. (2001) Taking the Train: How Graffiti Art Became an Urban Crisis in New York City. New York, Columbia University Press.

Bennett, B., Boidi, E., & Boles, I., eds. (2012) Christchurch: The Transitional City Pt IV. Christchurch, Free Range Press.

Bennett, B., Dann, J., Johnson, E., & Reynolds, R., eds. (2014) Once in a Lifetime: City-building after Disaster in Christchurch. Christchurch, Free Range Press.

Blanché, U. & Hoppe, I., eds. (2018) Urban Art: Creating the Urban with Art. Proceedings of the International Conference at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 15th-16th July 2016, Lisbon, https://www.urbancreativity.org/urban-art-berlin-conf.html

Castleman, C. (1982) Getting Up –Subway Graffiti in New York. Cambridge, Massachusetts/London, England, The MIT Press.

Chalfant, H. & Jenkins, S. (2014) Training Days: The Subway Artists Then and Now. London, Thames & Hudson.

Deitch, J. with Gastman, R. & Rose, A. (2011) Art in the Streets. New York/Los Angeles, Skira Rizzoli/MOCA.

Dickens, L. (2008) Placing post-graffiti: the journey of the Peckham Rock, Cultural Geographies, 15:471, http://cgj.sagepub.com/content/15/4/471.

Dr Suits (2015) Interview with Author, Christchurch.

French, B. ed. (2013) SCAPE 7 Volume Two: Artist Projects, Christchurch, SCAPE Public Art.

Gastman, R., & Teri, S. (2007) Los Angeles Graffiti, New York, Mark Batty Publisher.

Gorman, P., ed. (2013) A City Recovers: Christchurch Two Years After the Quakes, Auckland, Random House.

Grévy, F. (2008) Graffiti Paris, New York, Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Gröndahl, M. (2009) Gaza Graffiti: Messages of Love and Politics, Cairo/New York, The American University in Cairo Press.

Holman, J P. (2012) Shaken Down 6.3 – Poems from the second Christchurch earthquake, 22 February 2011, Christchurch, Canterbury University Press.

Hou, J., ed. (2010) Insurgent Public Space: Guerrilla urbanism and the remaking of contemporary cities, London, Routledge.

Howey, G. (2015) Please Demolish with a Kind Heart: Behind Christchurch’s Red Zone, Auckland, PQ Blackwell.

Lewisohn, C. (2008) Street Art – The Graffiti Revolution, London, Tate Publishing.

Liew, R. (dir.) (2014) If These Walls Could Talk, (Online web series) http://ifthesewallscouldtalk.co.nz.

Manco, T., Lost Art & Neelon, C. (2005) Graffiti Brasil, New York, Thames & Hudson.

McAuliffe, C. (2012) ‘Graffiti or Street Art? Negotiating the moral geographies of the creative city’, Journal of Urban Affairs, 34(2), 189–206.Merkins C., & Sheridan, K., (dir. & prod.) (2012) Dregs, Auckland, Dregs Ltd.

Munro, F. (2012) graf/AK, Auckland, Beatnik Publishing.

O'Donnell, E. (2007) InForm – New Zealand Graffiti Artists Discuss Their Work, Auckland, Reed Publishing (NZ) Ltd.

Parr, A. (2015) Remembering Christchurch: Voices from Decades Past, New Zealand, Penguin.

Parry, W. (2010) Against the Wall: The Art of Resistance in Palestine, London/Chicago, Lawrence Hill Books.

Paton, Justin, P. (2012) “Perimeter Notes: A Day Around the Red Zone”, Bulletin – Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, B.167, Autumn, March-May 2012, pp. 16–25.

Potts, A., and Gadenne, D. (2014) Animals in Emergencies: Learning from the Christchurch Earthquakes, Christchurch, Canterbury University Press.

The Press, (2010) The Big Quake: Canterbury, September 4, 2010, Auckland, Random House Rice, GW. (2008) Christchurch Changing: An Illustrated History (Second Edition), Christchurch, Canterbury University Press.

RomanyWG, (2011) Out of Sight: Urban Art / Abandoned Spaces, Great Britain, Carpet Bombing Culture.

Schacter, R. (2013) The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti, Sydney, Newsouth Publishers.

Sessions, L., & Bullock, C. (2013) Quake Dogs: Heart-warming stories of Christchurch’s dogs, Auckland, Random House.

Seno, E., (ed.), with McCormick, C, Schiller M & S, (2010) Trespass: A History of Uncommissioned Urban Art, Cologne, Germany, Taschen.

Silver, T. (dir.) (1984) Style Wars, New York, Public Art Films.

Smallman, J., & Nyman, C. (2011) Stencil Graffiti Capital: Melbourne, Brooklyn, New York, Mark Batty Publisher.

Solnit, R. (2010) A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster. New York, Penguin Books.

Stewart, J. (2009) Graffiti Kings: New York City Mass Transit Art of the 1970s, New York, Melcher Media/Abrams.

Strange, I. (2013) Final Act, 2013. [Online] www.ianstrange.com/works/final-act-2013/about/.

Tàpies, X A., Mathieson, E. (2007) Street Art and the War on Terror, The Complete Guide, London, Korero Books.

Uncredited. (2012) “Earthquake, 22/2 One Year On” supplement, The Press, Thursday, February 23, 2012, p. 4.

Uncredited, (2012) “How do you feel in buildings?”, The Weekend Press, Saturday, June 2, 2012, p. A3. Waclawek, A. (2011) Graffiti and Street Art, London, Thames & Hudson.

Workhorse & Pac, (2012) We Own the Night: The Art of the Underbelly Project, New York, Rizzoli.